5 Great Depression Success Stories

By Ethan Trex

These entities faced serious challenges during the Great Depression and lived to tell about it.

1. Floyd Bostwick Odlum

Many investors lost everything during the market crash of 1929 because they had mistakenly assumed Wall Street's good times were never going to end. Floyd Bostwick Odlum had, with some partners, cannily turned $40,000 [PDF] into a multimillion-dollar fortune by investing in utility companies. Odlum and his partners didn't like the way they thought the markets were moving, though. They cut bait on stocks in an effort to generate cash before the market crash Odlum thought was coming.

When the crash came, Odlum had millions in cash on hand, an enviable position in a cash-starved market. He began swooping in to buy up failing companies at drastically reduced prices and then consolidating or spinning their assets for more cash. It sounds like a pretty simple model, but it was so effective it made Odlum one of the wealthiest men in the country. The 1941 edition of Current Biography declared Odlum "possibly the only man in the United States who made a great fortune out of the depression."

2. Movies

The beginning of the Great Depression in late 1929 came at a particularly inopportune time for the film industry, which had recently evolved with the 1927 release of The Jazz Singer, a milestone talkie. Just as the industry seemed to be gaining momentum, unemployment shot up and the sort of disposable income one uses for little luxuries like going to the movies steeply declined. Early in the economic crisis, many moviehouses had to close their doors due to the decreased traffic, and most of the once-profitable studios started turning losses in the 1930s.

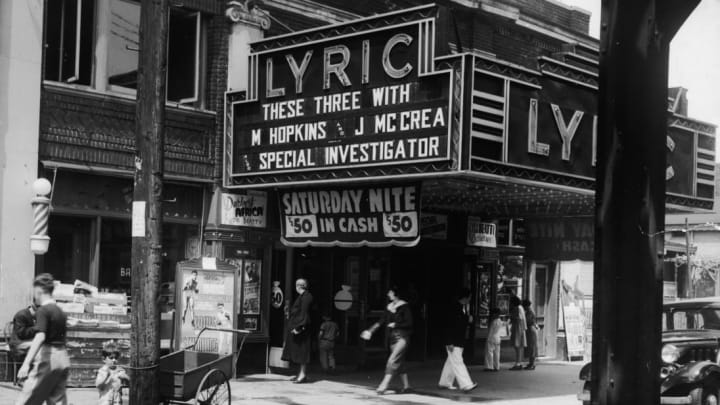

Faced with this glum market, the film industry got creative. To give customers maximum bang for their scant bucks, theaters cut ticket prices by 50 percent or more and started giving patrons two features for the price of one ticket. These double features propped up demand for cheaply made B movies, and smaller studios stayed afloat by banging out these quick products.

Theater owners resorted to even more desperate hucksterism, though. During the Depression it was fairly common for theaters to use giveaways to fill their seats. Promotions like "Dish Night," in which any woman who attended got a free dinner plate; cash door prizes; and silverware giveaways, where each trip to see a flick got you closer to having a complete set of flatware, helped buoy up attendance. Although box-office takes fell from $720 million in 1929 to $480 million in 1933, they slowly climbed back up to $810 million by 1941, in part due to these disaster-management tricks.

3. Procter & Gamble

The Great Depression was trying for most consumer product companies, but Procter & Gamble came out of the whole ordeal smelling better than it had in 1929. How did the soap giant [PDF] beat the Depression? Things were tough at first when mainstay grocery customers started cutting their orders and inventories piled up. P&G apparently realized that even in a depression people would need soap, though, so they might as well buy it from Procter & Gamble.

Thus, instead of throttling down its advertising efforts to cut costs, the company actively pursued new marketing avenues, including commercial radio broadcasts. One of these tactics involved sponsoring daily radio serials aimed at homemakers, the company's core market. In 1933, P&G debuted its first serial, Oxydol's Own Ma Perkins, and women around the country quickly fell in love with the tales of the kind widow. The program was so successful that P&G started cranking out similar programs to support its other brands, and by 1939, the company was producing 21 radio shows—and pioneering the “soap opera." In 1950, P&G made the first ongoing television soap opera, The First Hundred Years.

4. Martin Guitars

Like movies, musical instruments would seem to be a vulnerable industry in a down economy, but venerable acoustic guitar maker Martin made it through the Depression using a number of strategies. In addition to reducing its wages and operating on a three-day work week, the company also made everything from violin parts to wooden jewelry. The company stuck to its principle of not giving high-volume retailers discounts, which maintained its relationship with smaller dealers and cemented the company's image as a square dealer.

Martin also started offering new, less expensive models that went on to enjoy great popularity. The "dreadnought" body style (which traced its origins to earlier guitars made for a Boston publishing firm) was one of these triumphs; it included a larger, deeper body that provided more volume and bass resonance. Martin introduced its first archtop guitar in 1931, and the company also revolutionized its designs by using 14-fret necks on its guitars. These technical changes, coupled with Martin's dedication to giving its customers high-quality instruments at reasonable prices, helped keep its sales up throughout the Depression.

5. Brewers

The Depression was hard enough for most companies, but the nation's brewers had it especially bad. Sure, money was tight, but brewers’ core product, beer, wasn't even legal. During national Prohibition from 1920 to 1933, many of the country's breweries closed their doors for good—according to a 1932 Congressional Hearing, there were more than 1000 breweries before Prohibition began, but by 1932, there were “only 164 that could be ready to make beer again.”

How did these brewers make ends meet during the Depression when they couldn't sell suds to the distressed 25 percent [PDF] of workers who didn't have jobs? By diversifying. And then diversifying some more.

Brewers started running dairies, selling meat, and venturing out into other agricultural enterprises. Brewers were also allowed to make "near beer" that had only trace amounts of alcohol, but the Depression killed off consumer demand from 300 million gallons in 1921 to just 86 million gallons in 1932. Breweries also started applying their expertise to non-alcoholic tipples like root beer. Frank Yuengling, who headed the family brewery outside of Philadelphia, remained confident that Prohibition was just a phase, and he personally diversified widely, including opening a dance hall.

In the end, waiting out the storm by diversifying (and maybe brewing some illicit beer on the side) turned out to be a sound strategy. As of 2019, the five best-selling beers in America are all produced by pre-Prohibition/pre-Great Depression brands.