Inside the Augusta Cocoon

By Bud Shaw

When Tiger Woods announced he'd make his comeback at the Masters, a British bookmaker immediately installed him as a 4-1 favorite. A surer bet also available for gambling types online -- even though the odds make it a virtual coin flip -- is whether Woods will have to step away after addressing the ball because of a heckler.

Having been to Augusta several times, I'd say it's not likely to happen. And certainly not more than once.

It's not that I'm absolutely sure no one will heckle him. If someone does, though, that's when the truly stone-cold lead-pipe betting odds kick in. There's a 100 percent chance that person will be escorted out, never to return. And a 99 percent chance he or she will be dunked in Rae's Creek on the way just for good measure.

A Trip Down Magnolia Lane

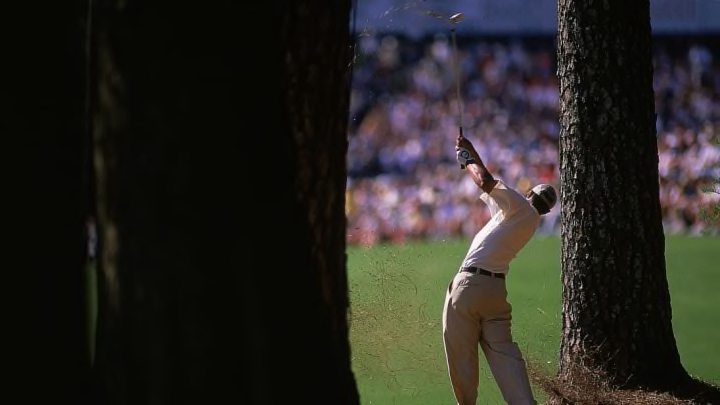

Tiger Woods has chosen the Augusta cocoon for obvious reasons. And reminders of why will present themselves to him as soon as he turns off Washington Rd. onto Magnolia Lane -- a paved entry to the Augusta biosphere named for the 61 magnolia trees that form a canopy stretching 300 yards to the clubhouse. [Image courtesy of Flickr user drod5044.]

That drive down Magnolia Lane was usually when the great golfer Lee Trevino started fidgeting. Trevino skipped the Masters for a few years and later admitted it was a mistake. But the exclusivity of the place always made him feel uncomfortable.

Merry Mex, as he was known, knew if he weren't a golfer he wouldn't be welcome anywhere near the place except through the kitchen. So Trevino refused to use the clubhouse even to change his shoes in the early to mid-1970s, choosing instead to use the trunk of his car as a locker.

Tiger Woods never knew that Augusta National. The club invited its first African-American member in 1990, years before Woods played at Augusta. For him, Augusta National is a safe haven, a place where he has not only won four times but where everything around him promises, as always, to be as controlled as a movie set. Once he parks his car, he'll go to the clubhouse. But not just any clubhouse.

Upstairs, above the one where invited golfers will dress, Woods will share a clubhouse with the past Masters' champions. Even the privacy at Augusta demands more privacy.

Media Relations

Woods will meet the media on the Monday after Easter. The issuing of media credentials is more limited at Augusta than at other tournaments. Not that TMZ or other outlets that made such an industry of the Woods scandal would've ever been welcome inside for the Masters anyway. But the credential application deadline passing before Woods announced his return allows the club to tell any number of media outlets, "Sorry, too late."

A club member emcees the player interviews at Augusta National. So when Woods does meet the press, he'll have a friendly face beside him orchestrating the proceedings. To say the treatment the emcee gives a guy like Woods is deferential doesn't quite cover it.

I've joked that usually by the time the interview is completed, Woods' shoes are spit shined, his ironed golf shirt collar is given turndown service and he's leaving a tip for the 30-minute chair massage. But I'm really only ruling out the the tip.

The media is allowed inside the ropes at most golf tournaments. Not at Augusta. At Augusta, everything and everyone conforms.

Lunch Break The prices for Augusta National's famed pimento cheese sandwiches and egg salad sandwiches haven't changed in years. They are wrapped in green paper, the litter under express orders to blend in should a gust of wind send it flying off for a tour of the course. [Image courtesy of Crazy Alex Luck.]

For the Birds

I began covering the Masters for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in the mid-1980s. I shared a handful of Masters tournaments with my co-worker and friend, Dave Kindred, winner of the Red Smith Award and long-time columnist for Golf Digest.

"(The Masters) is closer to what it started out to be than any sports event in the world," Kindred wrote me recently. "Bobby Jones wanted to invite his friends to his place. Still does. It's his place, not Budweiser's, not Traveler's, certainly not CBS's (it's the only sports event, I'd guess, that takes LESS money than a network could be muscled into offering).

"In exchange, it sets the rules of commercial time, use of network promotions, maybe even the bird sounds. There is less commercial signage at Augusta National than on the zipper of any NASCAR hero suit. I can say that because there is NONE. Nobody does that. Not even Wimbledon, where there's a Rolex sign at Centre Court. Good God, Augusta tapes over the Coca-Cola logos at the concession-stand soda fountains. Coca-Cola, the elixir of Atlanta!"

Once, Kindred tells me, he was hard-up for an early-week column. He watched workers mow the fairways. The precision impressed him. He thought he could make a column out of it. So he waited for the tractor/mower man to finish.

"Except when I stopped him, he said, 'No comment,'" Kindred remembered.

Kindred's reference to the "bird sounds" was in response to my mention that some reporters for years have walked around the grounds of Augusta National at a Masters tournament hearing the sweet songs of birds celebrating spring. Yet, some contend, they never actually see any birds. Were they donning camouflage?

Now that's control.

The Masters' Slogan Clearly Isn't "Have it Your Way" "¢ In 1966, Jack Whitaker of CBS refers to the golf fans standing around the green as a "mob." Augusta National prefers "patrons." Whitaker isn't invited back. "¢ In 1994, Gary McCord of CBS, looking for a way to get across how fast the Augusta National greens are says the club "doesn't cut the greens, it uses bikini wax." He said the lumpy terrain looks "like body bags." That was his last Masters. They don't just eject hecklers at Augusta. They eject golf announcers, too. "¢ When Lee Trevino balked at the $90 badge fee for his son one year, he vowed never to return to Augusta. Masters tournament chairman Hord Hardin wrote Trevino, saying, "We'll miss you but we'll try to go on without you." "¢ But by far the most glaring example of how insular Augusta can be, and also how it handles controversy, happened when Martha Burk took aim at its male-only membership policy in 2003. Representing the National Council of Women's Organizations, Burke wrote a letter to Augusta National Chairman Hootie Johnson urging the club to open its door to women members. Three weeks later, Johnson wrote her back, calling her letter "offensive and coercive." He said the club would admit women on its own timetable. He evoked the old south by saying the club would not act at the "the point of a bayonet." Burk put pressure on Masters sponsors to cut ties with the event. Augusta answered in a truly remarkable fashion, by putting on a commercial-free telecast. Burk arrived at Augusta National with a couple dozen supporters to protest during the tournament. They were further marginalized by the crazies -- a cross-dressing clown and a KKK member among them.

Crowd Control

Augusta National refers to the people who walk through its gates to watch the Masters as "patrons." Not fans. That's short for fanatics. Not galleries. Patrons. Every hole has a name associated with its predominant tree or shrub. So No. 1 isn't only No. 1. It's Tea Olive. No. 3 isn't just No. 3. It's Flowering Peach.

Golfer Mac O'Grady, who enjoyed a reputation as, shall we say, a free spirit -- OK, OK, his nickname was "Whack-o Mac-o" -- explained his poor play one year by saying he was "overcome by the biophilia" (an appreciation of life and the living world).

Golf fans are overcome by it, too, which is partly why the Masters ticket is so cherished. In the old days, tickets remained in the same family forever, but somewhere along the way the club revoked its family-succession plan. Tickets had to be used by the person named and could no longer be handed down or handed off to relatives.

When Kindred worked in Atlanta, he lived in the small town of Newnan, Ga. So did long-time Masters "patron" and cartoonist David Boyd. Boyd once quoted his aging mother to Kindred for a column.

"I visited her in the nursing home," Boyd told him. "Mother said to me, 'Every night I go to bed praying to die. Every morning I wake up praying thanks I'm alive. The Lord's keeping me alive for some reason. Only thing I can think of is the Masters tickets.'"

The story has long persisted that Augusta's membership never knows what its yearly dues are. Members are billed at the end of the golf season, the idea being that if you feel the need to ask what you're going to owe you're not Augusta material.

So if extra security is needed for Tigers Woods, I'm betting the club will probably be able to scrape it together.