6 Prehistoric Body Parts You Don’t See Anymore

Sometimes the sheer wonder of the natural world can be overwhelming. So, at the risk of oversimplifying the following crazy-cool animals, allow us to highlight their most unusual structural features. You may find yourself wondering why these body parts haven’t been around in many, many millenia.

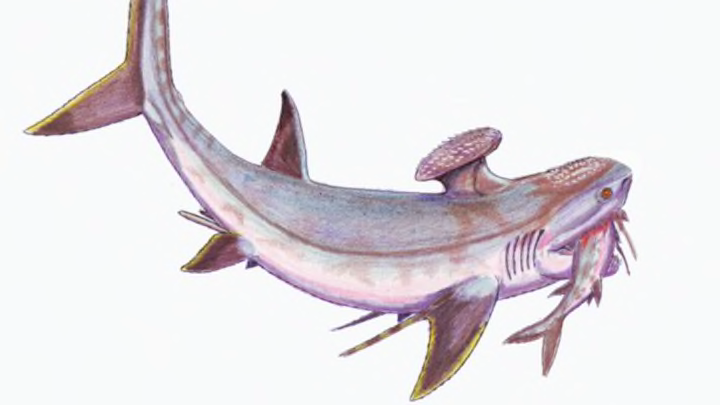

1. Anvil Fin - Stethacanthus

In most ways, Stethacanthus (above) probably looked like any of your average early sharks. Except, that is, for its bizarre anvil-shaped dorsal fin (sometimes described as an “ironing board”). Equally nonsensical is the rough patch of sharp, tooth-shaped scales atop the anvil/ironing board, and a second scaly patch on the top of its head which, like the anvil, seems pretty un-hydrodynamic.

At five to six feet long, Stethacanthus was among the smaller prehistoric sharks, and scientists have theorized that the weird dorsal shape might have served to mimic a huge mouth to deter would-be predators or competitors. But Stethacanthus wasn’t a very dynamic hunter, and probably stayed in shallower, coastal waters, feeding on small fish and crustaceans. More likely, the fin, the scales, and a pair of long, thin “whips” trailing from its sides have something to do with mating displays, as they’re only found on males of the genus.

2. Circular “Saw” Jaw - Helicoprion

Ray Troll

Helicoprion, a giant, shark-like “ratfish,” was host to one of the most notoriously baffling body parts ever discovered: a circular set of teeth that scientists now believe resembled a buzzsaw upended in the fish’s lower jaw. Back in 1899, scientist Alexander Karpinsky was left guessing after he discovered Helicoprion’s whirlygig of teeth sans the rest of the fish. For years, scientists and enthusiastic illustrators traded guesses as to how the teeth fit into an entire animal, which would prove to have reached lengths of 25 feet. They knew Helicoprion replaced its teeth intermittently, much like modern sharks, but it didn’t seem to share other sharky characteristics. The specifics of Helicoprion’s tooth replacement evaded them until earlier this year, when a team of Idaho State paleontologists pinned down the (still totally weird) mouth-mechanism seen here.

3. Tail Club - Ankylosaur

Wikimedia Commons

Most dino-inclined kids are well aware of the concept of the “tail club”: a tail which ends in a massive knob of bone and ossified tissue, good for defending against attackers, competing for mates, and knocking around whatever needs knocking around. Paleobiologist Victoria Arbour recently utilized CT scans to digitally reconstruct the muscles of the Ankylosaur’s tail club, allowing her to estimate the force with which the tail could smash. Her conclusions: Tail clubs with large “knobs” could break bone. Smaller-knobbed tail clubs, though, could do some lesser damage, leaving open the question as to whether tail clubs were more for offense, defense, or show. You know Ankylosaurs and their knob comparing.

4. “Baleen” Teeth - Pterodaustro

Wikimedia Commons

And speaking of size, Pterodaustro had the longest rostrum (snout) of any pterosaur, but its bottom teeth were truly the weirdest. Set in scooping underbite, its teeth were so long and skinny that they were all rooted a single, long groove in the bottom jaw instead of individual sockets. The overall effect is reminiscent of the baleen in modern whales, leading paleontologists to believe that Pterodaustro fed much in the same way, scooping up mouthfuls of muck from the shallows and filtering away the water to munch on what was left.

In modern whales, baleen is made out of keratin and is therefore more like hair than teeth, and for some time, scientists believed Pterodaustro’s teeth were composed of a similar protein. But closer inspection revealed microscopic evidence of real, toothy characteristics: enamel, dentine, and pulp cavities.

Here’s an hilarious and slightly outdated illustration of Pterodaustro in a synth rock video, for some reason.

5. The Ol’ Single Claw - Mononykus

Named for the Latin Mono-, meaning “one,” and nykus, meaning “nail or claw,” Mononykus olecranus is a dinosaur best known for having only one claw on each of its puny forelimbs. And you thought T. rex had it bad.

Scientists have entertained many competing theories over the years as to the behavior of Mononykus olecranus, whose forelimbs would have been fairly useless for hunting or even grazing. The supposed presence of a birdlike chest ridge had many scientists believing M. olecranus may have been a winged but flightless bird. But a 2005 study examining range of motion in those stubby forearms decisively concluded that M. olecranus would have used its claws to scratch into insect nests and scoop out food. In this way, Mononykus’ single claw is analogous to modern animals with similar diets like anteaters and pangolins, though their claw count isn’t quite so minimalist.

6. Shoulder Spikes - Gigantspinosaurus

With one of the most satisfying names in taxonomy, this dino is named after the gigantic spikes that were situated on his shoulders. Exactly how they were situated on those shoulders (and therefore their exact purpose) is yet unknown, though it’s reasonable to guess that they were used for displaying and/or competing for mates. And before you ask, Gigantspinosaurus is indeed a stegosaur, just one of several members of the genus Stegosaurus. Another of Gigantspinosaurus’ close relatives, Kentrosaurus, may have had similar spikes on its shoulders, or possibly on its hips (on this spike-placement question, the jurassic jury’s still out). But Gigantspinosaurus appropriately maintains the record of largest shoulder spikes in prehistory.

A very special thanks to our good friend, prehistorian Brian Switek, for lending his expert eye to this piece!