Second Balkan War Ends

By Erik Sass

The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 81st installment in the series.

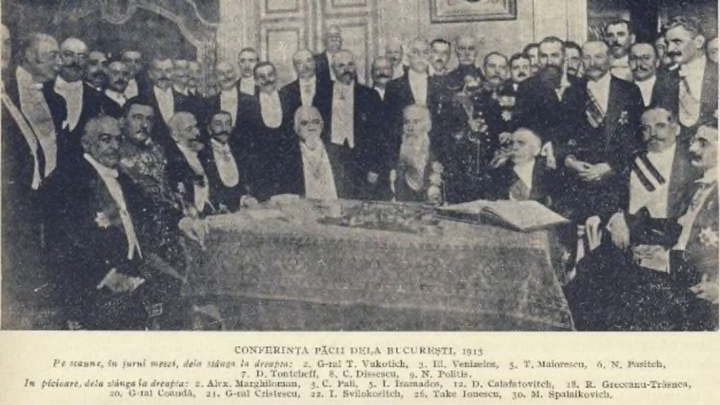

August 12, 1913: Second Balkan War Ends

After the Balkan League’s victory over the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War, Bulgaria attacked its former allies Serbia and Greece over the division of Turkish territory—but the Second Balkan War immediately proved to be a disastrous mistake. Following Serbian and Greek victories over Bulgarian forces in Macedonia, Bulgaria’s fate was sealed when Romania and the Ottoman Empire attacked from the rear. Bulgaria’s Tsar Ferdinand begged for peace on July 21, 1913, and ten days later, the belligerents met in the Romanian capital, Bucharest. The terms of peace were agreed on August 10, and on August 12, 1913, the Treaty of Bucharest was finally ratified, ending the Second Balkan War.

The Treaty of Bucharest stripped Bulgaria of most of its gains from the First Balkan War, as well as its own pre-war territory of Dobruja along the Black Sea coast. Between the First and Second Balkan Wars, Serbia increased its territory 82 percent, from 18,650 square miles to 33,891 square miles, and Greece grew 67 percent, from 25,041 to 41,933 square miles, with more than half of this coming at Bulgaria’s expense; adding insult to injury, Romania snipped off 2,700 square miles in Bulgaria’s northeast.

Most contemporary observers realized there was little chance of a lasting peace. Unsurprisingly, the Treaty of Bucharest left the Bulgarians embittered and resentful; in a few years, Tsar Ferdinand would lead his country into the maelstrom yet again, in an effort to redeem its lost territories and self-respect. The Second Balkan War also upended the diplomatic status quo in the Balkans, by turning Bulgaria against its traditional patron Russia, which had failed to protect Bulgaria against its enemies. Seeking a new protector among the Great Powers, Bulgaria turned to Austria-Hungary, which shared Bulgaria’s enmity towards Serbia and its backer Russia.

Indeed, on July 27, 1913, Tsar Ferdinand warned the Austro-Hungarian ambassador that “An opportunity has been wasted of wiping Serbia off the map. War between [Austria-Hungary] and Russia was inevitable and would come within a few years… The aim of his life was the annihilation of Serbia, which ought to be partitioned between Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary, and Romania…” On August 1, 1913, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count Berchtold—now converted to the idea of war by the hawks in Vienna—agreed that “in a not-too-distant future [Serbia] will compel us to have recourse to violent measures.” Meanwhile Russia was left with Serbia as its only client state in the Balkans, meaning the Russians had no choice but to back the quarrelsome Serbs in their future disputes, or risk forfeiting all their influence in the Balkans.

The Balkan states and their Great Power backers were on a collision course that was about to plunge the region, and the rest of Europe, into unimaginable bloodshed and misery.

Germans, British Partition Portuguese Colonies

While tensions were brewing in the Balkans, the situation in Western Europe seemed to be improving, as Britain and Germany worked to iron out longstanding sources of friction. After Germany accepted a compromise to slow the naval arms race in February 1913, in March the two leading Great Powers reached an agreement to settle the boundary between the British colony of Nigeria and the German colony of Cameroon. Then, in August 1913, they followed up with a preliminary agreement secretly divvying up Portugal’s African possessions.

Europe’s first colonial power, Portugal, led the conquest of Africa beginning in the 15th century, but like its fellow colonial pioneer, Spain, the small maritime state had suffered a long decline, surpassed by a new generation of colonial powers including Britain, France, and eventually Germany. It still held some large chunks of African real estate, in Portuguese West Africa (modern-day Angola) and Portuguese East Africa (modern-day Mozambique)—but as the unclaimed areas of the world shrank, it was only natural for the dominant colonial powers to turn their gaze to these remnants of empire, directly adjacent to their own African possessions.

Under the terms of the Anglo-German Convention agreed in principle on August 13, 1913, Britain and Germany assigned most of Angola—312,000 square miles in area, with a population of two million, located north of German Southwest Africa (Namibia)—to Germany, with Britain getting a small corner southeast of the Zambezi River. Meanwhile, most of northern Mozambique abutting German East Africa (Tanzania) would also go to Germany; the southern part of Mozambique, geographically contiguous with the Transvaal of British South Africa, would go to Britain.

The British and German representatives agreed to “compensate” Portugal with a $100 million loan on easy terms, but the agreement was still fairly treacherous on the part of the British, who were partners with Portugal in the world’s oldest alliance, the Treaty of Windsor, agreed in 1386; in fact, the British diplomat Arthur Nicolson called it “one of the most cynical diplomatic acts in my memory.” But British Foreign Minister Edward Grey was willing to strong-arm Britain’s weak ally in order to improve relations with Germany, a much larger and more important state.

In the end, the Anglo-German Convention was never ratified, as it was first delayed by predictable Portuguese objections, and finally superseded by the Great War. But the existence of even the preliminary agreement had an “excellent effect in clearing the air between England and Germany,” according to a contemporary analysis—and ironically, this may have contributed to the outbreak of war. As with the Nigeria-Cameroon boundary treaty, the Germans overestimated the importance of these colonial compromises to Britain: Of course British diplomats were happy to clear up minor disagreements about African borders, but that didn’t mean they were going to stand aside and let Germany violate Belgian neutrality, crush France, and establish hegemony in Europe. In less than a year the Germans would pay a heavy price for this fatal miscalculation.

See the previous installment or all entries.