Mr. Mumler’s Ghosts: The Father of Spirit Photography

“You may deceive the human eye, say the advocates of spirit materializations, but you cannot deceive the eye of science, the photographic camera.”

— Henry Ridgely Evans

The 19th century was the first time in Western history that most people could not only read, but had the leisure time to do so. This made for many new ideas. New religions, for example, popped up throughout America. Among them was Spiritualism, the belief that souls live in the spirit world after death and can still be contacted.

Another new idea, photography, was taking the country by storm at the same time. Take these two concepts, add a war that killed millions of loved ones, filter through a few hucksters, and you’ve got Spirit Photography.

Double the exposure = double the money

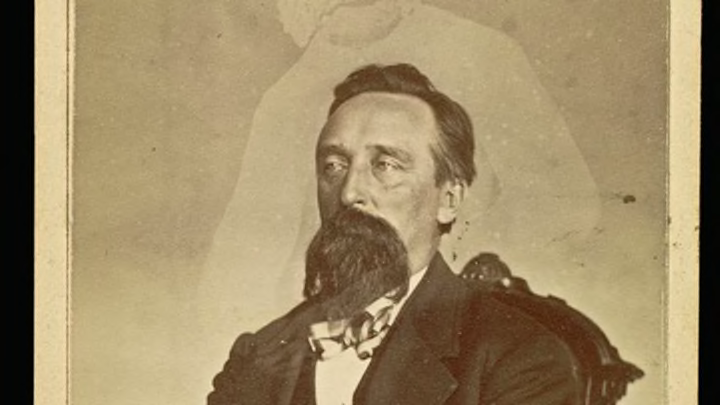

Bostonian William H. Mumler was the first prominent Spirit Photographer. He was a jewelry engraver in the early 1860s, and dabbled in photography as a hobby. One day a self-portrait he developed appeared to have the ghostly figure of a young girl in the background. Mumler figured it was an after-image of another sitter, as photographic plates were reused and it wasn’t unheard of for a previous image to remain slightly imprinted on a cleaned plate. But then again, the imprint also kind of looked like his dead cousin. Spirit photography was born.

A contemporary publication, Henry Ridgely Evans’s 1897 The Spirit World Unmasked: Illustrated Investigations Into the Phenomena of Spiritualism and Theosophy, describes two ways it was possible for the unscrupulous to capture the image of “spirits”:

There are two ways of producing spirit photographs, by double printing and by double exposure. In the first, the scene is printed from one negative, and the spirit printed in from another. In the second method, the group with the friendly spook in proper position is arranged, and the lens of the camera uncovered, half of the required exposure being given; then the lens is capped, and the person doing duty as the sheeted ghost gets out of sight, and the exposure is completed. The result is very effective when the picture is printed, the real persons being represented sharp and well defined, while the ghost is but a hazy outline, transparent, through which the background shows.

It All Checks Out

People were skeptical of Mumler’s abilities to capture the dead on film from the start. There are accounts of many professional photographers of the day going to oversee his process. The strange thing was most came away finding no evidence of fraud.

In 1863, The Journal of the Photographic Society of London reported the experiences of a “practical photographer” who was sent to scrutinize Mumler’s work. The photographer, William Guam, came away convinced in Mumler’s ability:

Having been permitted by Mr.; Mumler every facility to investigate, I went through the whole of the operation of selecting, cleaning, preparing, coating, silvering, and putting into the shield the glass upon which Mr. M. proposed that a spirit-form and mine should be imparted, never taking off my eyes, and not allowing Mr. M. to touch the glass until it had gone through the whole of the operation. The result was, that there came upon the glass 3 picture of myself and, to my utter astonishment—having previously examined and scrutinized every crack and corner, plate-holder, camera, box, tube, the inside of the bath, &c. —another portrait.

Guam insisted his both his dead wife and father were present in pictures printed by Mumler, which was especially gratifying as he claimed had been hoping they would appear to him while the pictures were being taken.

The Unknown Widow

Other critics were not so easily convinced. It was claimed that some of Mumler’s ghosts were actually his previous sitters, and many of them were live, recognizable Bostonians. In 1869, the New York Police brought a lawsuit against Mumler, claiming he was defrauding people who were suffering terrible grief. Outspoken celebrities of the day decried him as a fraud and much was written on how easy it was to fake a ghostly imprint. He was acquitted at trial, but the scandal ruined his reputation as a true spirit medium.

His career held out long enough for him to have one more famous sitter. A woman, who Mumler claimed was a complete stranger to him, came to sit for him in 1871. The resulting photograph is considered to be the last known photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln, with her dead husband standing behind her.

Photo courtesy of the Allen County Public Library

Mumler died in 1884. There are no known photographs of him beyond that date.