10 Crazy Creations of “Plant Wizard” Luther Burbank

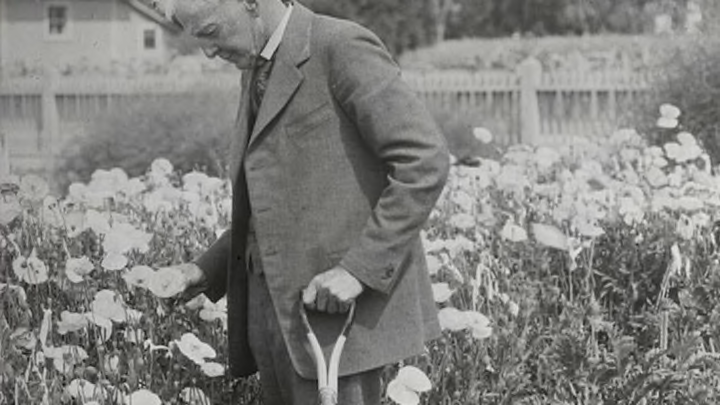

Even if you've never heard of Luther Burbank, you've probably tasted his work the last time you ate a French fry. In the early 20th century, Burbank—who was born on March 7, 1849—created over 800 varieties of fruits, flowers, and vegetables. The "Plant Wizard," as he was called, had a unique approach to horticulture that was part Darwinism, part Thomas Edison. And while his failures often sound like something out of a sci-fi novel, we’re still eating many of his creations today.

1. RUSSET POTATO

Luther Burbank’s career started with a tiny seedpod growing on a potato plant in his garden. Most people would disregard the inedible seedpod, but Burbank had been reading Charles Darwin. Intrigued by Darwin's idea that each plant contains countless possible variations, he planted the 23 seeds. Only two of the resulting plants produced potatoes, but one of them was a doozy. It yielded tons of big potatoes with thin brown skin and white flesh. Today, a slight variation of this potato (due to a spontaneous mutation in a farmer’s field) is used in everything from tater tots to french fries.

2. SHASTA DAISY

Burbank was fond of daisies, so he set out to invent his ideal version of one. He wanted large, white blossoms that would bloom for a long period of time. First, he cross-pollinated the oxeye field daisy with the English field daisy. Then he took the best of those plants and crossed them with the Portuguese field daisy—a process that took six years.

Still unsatisfied—apparently the flowers weren’t white enough—he pollinated these triple hybrids with the Japanese field daisy, which was known for its white blossoms. The result was a flower close to the one in his imagination. He introduced the Shasta Daisy, which took 17 years to make, in 1901.

3. PLUMCOT

The plumcot is half plum, half apricot. Burbank crossed the Japanese plum with an apricot and kept refining until he had a fruit with plum-like flesh and the aroma of apricot. Prior to the plumcot, people thought it was impossible to cross two trees with such different fruit; the plumcot opened the door.

(The plumcot is different from the pluot, which is 60 percent plum and 40 percent apricot, as well as the aprium, which is 70 percent apricot and 30 percent plum. Both fruits came after the plumcot.)

4. WHITE BLACKBERRY

Much of Burbank’s success came from making plants perform functions that seem the opposite of their nature. This is the case with the white blackberry. Its very name is a contradiction. Burbank created it by crossing a brownish blackberry called “Crystal White” with the Lawton blackberry.

Unfortunately, the plant is one of Burbank’s commercial failures. Once the novelty wore off, the public just wasn’t interested in eating white blackberries.

5. SCENTED CALLA LILY

One night, Burbank was walking among his calla lilies when he caught the scent of violets. That struck him as strange, because calla lilies aren’t supposed to have a smell. Burbank dropped to his knees and began crawling around in the dark, smelling flowers until he detected the source of the scent. From there, he came up with a sweet-smelling calla lily called “Fragrance.”

6. SPINELESS CACTUS

This is, simply put, a cactus without spines. It took Burbank two decades to remove the cactus’s spines, a process he called soul testing. “For five years or more the cactus blooming season was a period of torment to me both day and night,” he said.

Burbank hoped the spineless cactus would transform deserts into places where cattle could graze. At first, it seemed like a success, with people like author Jack London testing the spineless cactus at his nearby ranch. But it turned out that the spineless cactus was delicate. It didn’t like cold and needed regular watering—in short, it couldn’t survive in the desert. Burbank’s most arduous project was also his biggest commercial failure.

7. POMATO

You’d be forgiven for assuming the pomato is a cross between the potato and tomato, but in fact, it was a fruit that grew on a potato vine. It looked like a white tomato and Burbank described eating it as “a delightful commingling of acids and sugars.” Because of its resemblance to the tomato, he called it the pomato.

Unfortunately, the pomato was a fluke. It never reproduced the same way again, and Burbank didn’t take enough interest in the plant to continue with it.

8. PETUNIA/TOBACCO HYBRID

One of Burbank’s more eccentric failures was when he tried to cross a tobacco plant with a petunia. The resulting plants sound like mutants out of Little Shop Of Horrors: Some plants turned red or pink, while some stayed green and popped out petunia flowers. Some of the plants tumbled over and trailed vines while others grew four feet tall and sprouted tobacco leaves. Burbank weeded out the tobacco-like plants in favor of petunia characteristics, only to find they had a weak root system. He joked that the petunias were stunted from their tobacco habit.

9. PARADOX WALNUT

In his career, Burbank developed walnuts with thinner shells, bigger kernels, and larger yields. His biggest achievement wasn’t in the nut, however, but in walnut wood. The Paradox Walnut is a cross between the California black walnut tree and the English walnut. When he planted the seeds from this hybrid, it grew so quickly that it soon dwarfed the other walnut trees. In 15 years, the Paradox Walnut was 60 feet tall with trunks measuring two feet wide. Other walnut trees would take 50 to 60 years to get that big.

10. “MIRACULOUS” STONELESS PLUM

Wouldn’t it be nice to eat a plum without having to bother with the stone? Burbank thought so, so he set about making a plum without a pit. He started with a plum called Sans Noyau, which naturally had a stone about half the size of other plums. From there, he developed a plum with only a tiny flake of seed in its center.

But the plum wasn’t well received, and for years, Burbank’s stoneless plum was thought extinct. Then one of the original Burbank trees turned up in Oregon. Learn about horticulturalist Lon Rombough’s efforts to preserve Burbank’s stoneless plum here:

Additional Sources: Luther Burbank Online; LutherBurbank.org; video from Archive.org; NPR; Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application.