How Thomas Jefferson Reinterpreted the Bible

Thomas Jefferson had a complicated relationship with religion. While deeply interested in theology, morality, and religious studies, and a major advocate for religious freedom (he was a product of the Age of Enlightenment after all), his aversion to the Orthodox Christianity of the time led him to be accused of atheism. Not helping his cause: Jefferson was known to take a knife to the Bible itself.

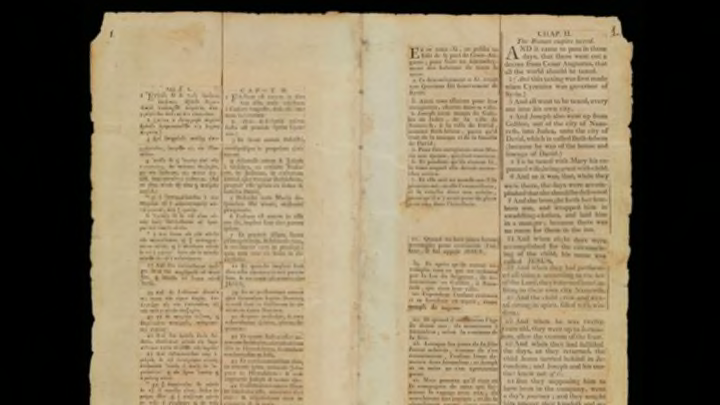

In 1820 (six years before his death), he created an 84-page red leather-bound volume titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Jefferson had done close reads of the New Testament, comparing translations in Greek, Latin, French, and King James English before cutting into them with a penknife, razor or some other sharp object. He manually cut and pasted together an entirely new book with Greek and Latin on one side, with French and English on the other.

In broad terms, Jefferson got rid of redundancies, placed events in chronological order, and edited out instances of the miraculous. In his version, there's no multiplying of loaves and no resurrection. The focus instead is on the teachings of Jesus and the lessons of morality therein. Jefferson was troubled by what he saw as misinterpretations of those teachings and distrusted the writers of the gospels, which is why he sought to compile a philosophical text that was free of meddling middlemen

In a letter to John Adams in 1813, Jefferson wrote: “We must reduce our volume to the simple evangelists, select, even from them, the very words only of Jesus ... There will be found remaining the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has even been offered to man.”

It wasn’t his first customized bible—Jefferson crafted another one earlier in 1804 while he was still president. That version was lost, but its existence illustrates a lifelong dissatisfaction with the tome. The project wasn’t that of a missionary; Jefferson kept his custom bible largely to himself, though wear and tear on the book suggests that he consulted it often.

The Smithsonian acquired Jefferson’s bible in 1895 when chief librarian Cyrus Adler bought it from Carolina Randolph, Jefferson’s great-granddaughter. It was later printed in 1904 and up until the 1950s, was given to each newly elected senator on the day he or she took the oath of office. The tradition ceased when the 9,000 copy supply ran out.

You can read the Jefferson Bible in its entirety over at the Smithsonian.

Screenshot via The Smithsonian

[h/t Open Culture]