10 Plans to Weaponize Animals

By Janet Burns

Animals have been getting roped into human warfare for millennia and have played many parts in and out of battle: the practice of using war horses dates back to as early as 4000 BCE, while trained specialists like carrier pigeons and the much-decorated Sergeant Stubby (whose 1926 New York Times obituary noted the dog had “[entered] Valhalla”) have been celebrated for their crucial contributions to modern warfare.

But while Hannibal’s elephants made all the history books for their (almost entirely fatal) battlefield glory, thousands of animals have endured testing—and even occasional deployment—as living deliverers of disease, flying bombs, and detonators on legs in almost total obscurity.

To honor our feathered and furry friends who almost performed the ultimate sacrifice in war (or, in some cases, very much did), here are 10 military plans to weaponize animals.

1. COLD WAR NUKES KEPT COZY (‘TIL DETONATION) UNDER LIVE CHICKENS.

As was summarized by the BBC, a 1957 document reveals a plan—one seriously considered by the British Civil Service—to bury a seven-ton nuclear land mine in West German soil as a preventative measure against any encroaching Red Army forces. However, as the BBC points out, “nuclear physicists at the Aldermaston nuclear research station in Berkshire were worried about how to keep the land mine at the correct temperature when buried underground.”

The proposed solution, according to this document, was to fill the bomb’s casing with live chickens, which, “given seed to keep them alive and stopped from pecking at the wiring,” would generate enough heat living out the rest of their poultry lives “to ensure the bomb worked when buried for a week,” after which it would be detonated remotely. Thankfully for the birds (and West Germans), the plan was never realized.

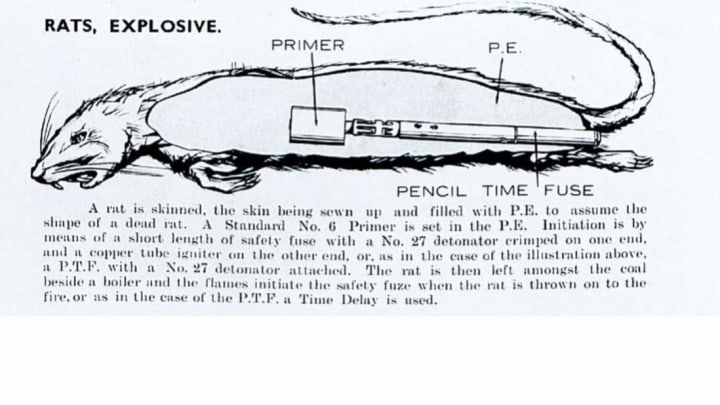

2. EXPLODING (DEAD) RATS HIDDEN IN COAL SHIPMENTS ...

The British Special Operations' idea to slip explosive-filled dead rats in enemy coal loads was developed in 1941, the BBC notes, and sought “to blow up the enemy's boilers ... with the fuse being lit when the rat was shovelled into the fire.” Dead-rat warfare was never put into practice, though, “as the first consignment was seized by the Germans and the secret was blown.”

The BBC points out that German military leaders “were fascinated by the idea, however, and the rats were exhibited at the top military schools,” leading German forces to perform searches of their coal stores for rat bombs before satisfying themselves that the plan had fizzled out. As to where British forces got their supplies of dead rats, it was a fair example of the Biblical idiom “they know not what they do” come to life: “The source of the dead rats was a London supplier, who was under the mistaken belief that it was for London University.”

3. … AND SOVIET RATS THAT FUNCTIONED AS BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS.

During the same war, Soviet military researchers proved that a rat’s value as a weapon isn’t limited to being stuffed with explosives. In 1942, Soviet forces used disease-bearing rats against Friedrich von Paulus's troops during the Battle of Stalingrad; rather than attempt to sicken the Germans with plague or anthrax—which was too dangerous for their own side as well—the Soviets instead infected rats with tularemia, a serious bacterial infection that causes weakness, fever, and skin ulcers at the site of infection. The result? As biological weapons experts Milton Leitenberg and Raymond A. Zilinskas explain:

At first, the success was surprising: Without reaching the Volga, Paulus was forced to halt his attack at Stalingrad [and] approximately 50 percent of the German soldiers who entered the Soviet camps after the Battle of Stalingrad suffered classical symptoms of tularemia. Unfortunately, however … [the] disease cross the frontline, and Soviet soldiers filled the infirmaries.

4. IN WWII, DOGS WERE STRAPPED WITH ANTI-TANK MINES.

As historian Steven J. Zaloga explains (and this footage seems to illustrate), Soviet forces began to develop “a ‘guided’ anti-tank mine” in 1941 using trained dogs, and which can’t be called a rousing success for either the animals or the army:

The dogs were kept hungry, and trained to crawl under tanks to get their food. In the combat area they were fitted with a special fabric harness which contained 10-12kg of high explosive in four pouches. At the top of the harness was a spring-loaded trigger pin. When the dog crawled under a tank the trigger pin was depressed, setting off a detonator and exploding the charge.

Seem reasonable? In any case, German forces “soon learned about this scheme from prisoners, and in sectors where they appeared, dogs in the combat area were shot on sight.” And while sources in the Soviet army “claimed that 16 dogs destroyed 12 German tanks” in the 1943 Battle of Kursk, “German sources claim that the mine dogs”—with their species’ famously keen sense of smell—"were not very effective, apparently because they were trained under diesel-engined Soviet tanks, not petrol-engined German tanks,” and tended to head toward the home team when in doubt about their dinner.

Maybe four-legged creatures simply weren’t the right delivery system for bombs—a thought that might’ve occurred to the U.S. teams who spent part of the second world war trying to perfect the bat bomb instead.

5. IN THE CIVIL WAR, MULES WERE MOBILE BOMBS.

Sadly for those WWII soldiers and dogs involved in the “guided anti-tank mine” scheme, their Stavka masters apparently weren’t very familiar with the history of the American Civil War. In 1862, Union forces in Texas similarly attempted a “particularly cruel scheme to 'mow down guys in gray like ripe wheat’” using two mules. Historian Marilyn W. Seguin explains:

Captain James Graydon ordered his men to pack a number of 24-pound howitzer shells into wood boxes and then lash them to the backs of a pair of mules … When they were within 150 yards of the unsuspecting Confederates, the Federals lit the fuses, gave each animal a hard smack on the rear, and ran for their own lines. The mules moved into action—they turned and followed their drivers instead of going forward towards the Confederates. One observer wrote: 'Every one of them shells exploded on time, but there were only two casualties—the mules.

The strange tactic did have a beneficial effect for the Union army, however, if an unintended one; Robert Lee Kerby points out that “the explosions stampeded a herd of Confederate beef cattle and horses into the Union's lines, so depriving [Confederate] troops of some much-needed provisions and horses.”

6. “BUG” AND “MAGGOT BOMBS” KILLED 440,000 IN CHINA DURING AND AFTER WWII.

Dogs and rats aside, research on weaponizing animals in the past century has mostly focused on the potential impact on an enemy of infected insects. "At the turn of the 20th century, man started to understand that insects are the vector of disease," explained University of Wyoming professor Jeff Lockwood to the Casper Star Tribune. "The Japanese, French, Germans, English and the United States all had entomological disease programs active during the golden years of 1930 to 1970”—including the Japanese World War II program Unit 731, the Tribune points out:

Lockwood suggests in an article for the Boston Globe that the number of fatalities from this project, which “sprayed disease-carrying fleas from low-flying airplanes and dropped bombs packed with flies and a slurry of cholera bacteria,” could well exceed the deaths of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings: he notes that the Japanese effort “killed at least 440,000 Chinese using plague-infected fleas and cholera-coated flies, according to a 2002 international symposium of historians.”

The Tribune notes that this history of these attacks remains largely unknown—something that Lockwood suggests “is because the United States cut a deal with the Japanese unit not to try them as war criminals if they would share their information on insect weapons.” With their new knowledge, U.S. military researchers “eventually settled on the use of yellow fever mosquitoes during the Cold War, and even dropped uninfected mosquitoes on its own citizens in parts of Georgia to test the frequency of bites,” the Tribune writes.

7. FLEAS WERE TESTED AS CARRIERS IN “OPERATION BIG ITCH.”

Military historian Reid Kirby explains that U.S. forces have also experimented with using fleas—having a strong track record of transmitting deadly Black Plague several hundred years earlier—as a delivery system for disease:

Operation Big Itch used uninfected fleas to determine the coverage patterns and the suitability of the tropical rat flea ... in terms of survival and appetence. The field trials were conducted at Dugway Proving Ground [Utah] in September of 1954 [and] used guinea pigs, placed at stations along a 660-yard circular grid, to detect the presence of fleas.

The bombs used were designed to hold as many as 200,000 fleas each, and Operation Big Itch tests reportedly “showed that the fleas could survive the drop and would soon attach themselves to animal hosts on the ground.” There was an obvious downside, though: Some canisters would come open while still in the air, and in addition to the poor, patriotic guinea pigs on the ground, “the pilot, the bombardier and observers on the planes were also bitten many times.”

8. POTATO BEETLES WERE SUPPOSEDLY AIR-DROPPED TO DESTROY ENEMY CROPS.

Nonbiting bugs have had their place in the history of animal warfare, too, including the seemingly humble Colorado potato beetle. As the BBC reports, the early 1950s saw a number of East German press reports of “cases in which planes flying overhead had been followed by a plague of potato beetles,” which were previously uncommon in the region and seriously threatened already strained food supplies. As a result, “[politicians] raged against the ‘six-legged ambassadors of the American invasion’ and [the] ‘criminal attack by American imperialist warmongers on our people's food supply,'” and started an aggressive propaganda and farming how-to campaign encouraging children to help eradicate the pests one by one.

French forces had, in fact, “considered importing beetles from the U.S. and dropping them over Germany after World War I—but the plan was abandoned due to fears it might also damage French agriculture.” German military researchers themselves even “performed a number of tests dropping specially-bred potato beetles out of planes in 1943,” but the idea never got airborne.

9. BEEHIVES WERE PROJECTILE WEAPONS IN PREHISTORIC TIMES.

Entomological warfare doesn’t always have to be so complicated, of course. Jeffrey A. Lockwood suspects early Paleolithic humans were using insects in battle 10,000 years ago or even earlier. At the time, humans often "lived in caves and rock shelters—prime targets for a hurled nest of bees or hornets and related wasps," and while "an inanimate objects thrown over a stockade was unlikely to find its mark, a hive of bees was another matter altogether … an angry swarm," perhaps pacified by smoke and transported in a bag to the enemy's gathering point, "might break the siege and drive a frantic enemy into the open."

10. PIGEONS WERE TRAINED AS ON-BOARD MISSILE GUIDANCE SYSTEMS.

In addition to being tried out as delivery systems for bombs and biological warfare, some animals were even given special skills in the name of military innovation. In WWII, the U.S. navy was faced with the problem of trying to quickly improve their "large … primitive … rudimentary electronic guidance systems" so as to pose a real threat to tough German Bismarck battleships with more accurate missiles, Military History Monthly notes. Always game (and usually successful) in a pinch, Harvard psychology professor and "jack-of-all-trades" B.F. Skinner stepped up with a solution: trained pigeons, placed inside missiles' nose cones, would guide them by "tapping a target on a screen with their beaks to control the direction." Pigeons were trained in laboratories to peck at shapes or projected images of target ships and were rewarded for the accuracy with grain, and were so effective at this task that Skinner "vowed never again to work with rats."

Nevertheless, the program was shelved by the military in October of 1944, as military leaders, the magazine notes, "were of the opinion that ‘further prosecution of this project would seriously delay others which in the minds of the Division have more immediate promise of combat application’. Namely (although unbeknownst to Skinner), Radar."

The result of the project, in the end, was that "Skinner was bitter. ‘Our problem was no one would take us seriously,’ he complained."