A Three-Minute Test Diagnoses Lewy Body Dementia

Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) is a neurological condition that affects an estimated 1.4 million people in the U.S. alone, but very few people have ever heard of it. Even clinicians struggle to diagnose it because it overlaps with many other similar disorders such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's—in fact, 80 percent of LBD cases are misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s—and psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia. Before his death, actor Robin Williams had been diagnosed with Parkinson's, but an autopsy found "diffuse Lewy body dementia" in his brain. Now clinicians have a way to diagnose the disease.

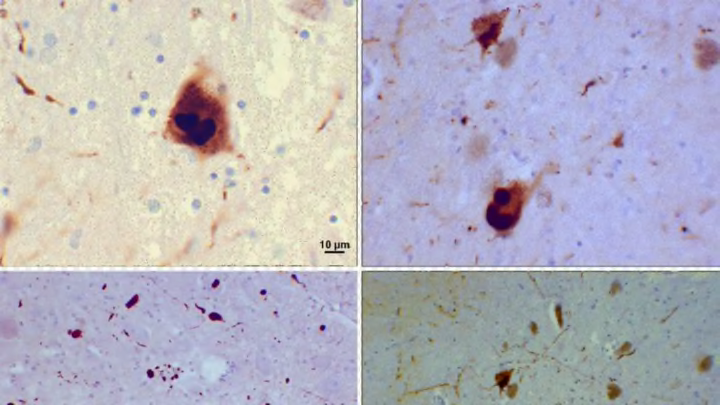

Technically, Lewy bodies are abnormal proteins called alpha-synuclein, but they're better known by their eponymous name; Dr. Friederich Lewy, a German neurologist, discovered them in 1912. When they accumulate in neurons, they disrupt brain function, causing cognitive decline, Parkinson’s-like tremors and motor problems, and memory problems.

Since there are no identified biomarkers to easily diagnose LBD, Dr. James E. Galvin, a professor and associate dean for clinical research at the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University, has created a 3-minute test called the Lewy Body Composite Risk Scale (LBCRS), comprised of 10 questions [PDF], to which a patient must only get three “yes” answers to qualify as having LBD. The test is meant to be administered in a doctor's office.

In a test-run of its accuracy in a real-world clinic setting, with 256 patients representing a "mixture of gender, education, comorbidities, behavioral, affective, motor symptoms, and diagnoses," the LBCRS was able to discriminate between Alzheimer's disease and LBD with 96.8 percent accuracy. These results were recently published in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

“In the absence of a biomarker, you need a tool that can capture these symptoms and frame them in a way that every clinician can ask every patient the same questions and either rule it out, or make the diagnosis likely,” Galvin says.

Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

Diagnosis of LBD is difficult because some symptoms are hard to quantify. “For instance, one of the core features of LBD is cognitive fluctuations, but there is no well-agreed upon definition of these," Galvin explains. "The general consensus is that cognitive fluctuation is a spontaneous change in level of attention, alertness, or focus that can vary from minute to minute, hour to hour. So how do you capture that symptom?”

To make matters more complicated, Lewy bodies are found in many parts of the body, which can cause symptoms that masquerade as other conditions: “You’ll find [Lewy bodies] in the peripheral nervous system, the walls of the gut, the heart, in salivary glands, in sebaceous glands and more,” Galvin says. “Because of this, some of the early symptoms include chronic constipation, heart arrhythmias, changes in salivary glands—drooling—and even dermatitis.”

Though it’s often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s due to the shared decline in memory, there are some significant memory differences between the two illnesses. “Alzheimer’s patients have difficulty learning new information, whereas non Alzheimer’s-dementias, including LBD, are better able to learn information but have difficulty retrieving information,” Galvin says.

LBD patients also have more visual-perceptual problems. “Many of these patients first go to an eye doctor because they think something is wrong with their glasses.”

Though there is not yet a cure for LBD, early diagnosis is helpful for patients, not the least because it can ease the strain that uncertainty puts on families. “[Not having a diagnosis] creates a sense of isolation when no one can explain what’s going on,” Galvin says.

Early diagnosis is also crucial when it comes to treating symptoms with medications. To treat the various symptoms that occur with LBD, Galvin says, “we borrow medications from other fields. We use Alzheimer’s meds and Parkinson’s meds, and meds from the psychiatric field and the cardiology field.”

Without a diagnosis of LBD, undiagnosed individuals are at risk for a dangerous condition resulting from neuroleptic medicines—antipsychotics—which are prescribed for hallucinations or schizophrenia-like symptoms. That's because they affect the brains of people with LBD differently, Galvin says: “LBD patients have a tenfold increased risk of getting neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which is characterized by high fever, muscle breakdown, kidney failure, and even death.” The earlier the diagnosis, the less chance of this happening.

Because the Lewy Body Composite Risk Scale is so new, it's not in use much yet. But Galvin is hopeful that eventually his test will help millions of people with the disease get a diagnosis and some form of symptom treatment. He stresses the need for greater awareness of the disease—and more research dollars to study it.