The Uterus: A Natural History

At only 3 inches long and weighing about 60 grams, the uterus isn’t a flashy, attention-grabbing organ. When it comes to human health, the heart usually comes first, followed by the brain, then perhaps the digestive system. Yet the uterus plays an outsized role. It’s the carrier of all life, the subject of scrutiny in political forums, and a source of delight and despair for sexually mature women. It causes bleeding and pain, allows 211 million women to get pregnant every year, and is partially responsible for the 10 to 20 percent of those pregnancies that end in miscarriage.

Despite its ability to create life, there are dozens of crucial things we have yet to learn about the uterus. At least we’ve abandoned the theory that it travels freely around the body, causing hysteria, and that it can be manipulated by smelling salts.

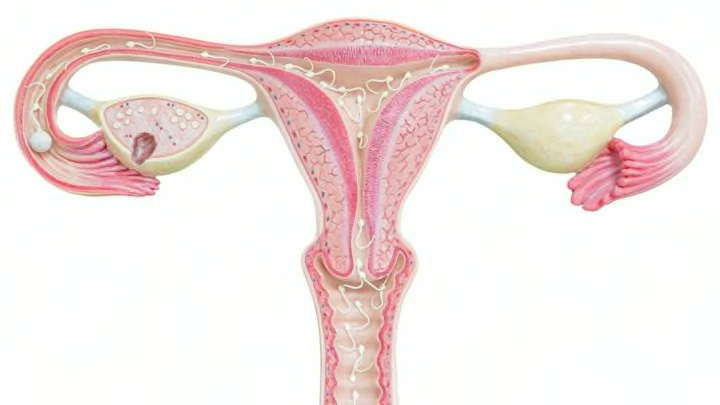

Today we know the uterus sits low in the abdomen, held in place by muscles and ligaments. It is connected to the vagina by the cervix and receives unfertilized eggs from the ovaries via the fallopian tubes, which are connected to both sides of the uterus. It expands from 3 inches to the size of a watermelon by the end of a pregnancy in order to hold the baby and placenta—and, luckily for new mothers, naturally deflates about six weeks after the child is born.

But how did we develop this organ, how does it operate—or malfunction—in the body, and what's the outlook for the future?

THE EXTRAORDINARY EVOLUTION OF THE MAMMALIAN UTERUS

Until recently, scientists didn’t even understand how mammals evolved uteruses that allowed for live birth. Soft tissue is rarely preserved in the fossil record, which means scientists can study the bone structure of past organisms but are often left guessing when it comes to organs.

Up until marsupial ancestors appeared 220 million years ago, new life came out of eggs. Before that time, even the earliest mammalian predecessors, the group called monotremes (like echidnas and platypuses) were still laying eggs. But by 105 million years ago, placental mammals had evolved elaborate uteruses that allowed for invasive placentas, maternal tolerance of the fetus, and long gestation periods. What caused this evolution? Why did mammals suddenly appear?

In 2015, a team of researchers from the University of Chicago, Yale, and several other universities found a major clue in the hunt to discover the origin of mammals: genetic parasites. Called transposons, these snippets of non-protein-coding DNA regularly changed positions in the genome, an action called “jumping genes.” The leap-frogging transposons caused genes from other tissues—like the brain and digestive system—to be activated in the uterus. As more and more genes were expressed in the uterus, organisms shifted from producing eggs to giving live birth. The shift began sometime between 325 and 220 million years ago with the appearance of monotremes, and continued for hundreds of millions of years until placental mammals appeared, sometime between 176 and 105 million years ago.

During the genetic shift, more than 1000 genes turned on in therians, common ancestors to marsupials and placental mammals (like us). Many of these genes related to maternal-fetal communication, and especially the suppression of the maternal immune system in the uterus so it didn't reject the developing fetus. Because many of the transposons had progesterone binding sites that regulated the process, the uterus evolved to be extremely sensitive to that hormone (which is produced by the ovaries during the release of a mature egg; it prepares the uterine lining to receive a fertilized egg). The study appeared in the journal Cell Reports. In a press statement, Vincent Lynch, one of the study’s authors, said the discovery shed light on how “something completely novel evolves in nature.”

“It’s easy to imagine how evolution can modify an existing thing, but how new things like pregnancy evolve has been much harder to understand,” Lynch continued. “We now have a new mechanistic explanation of this process that we’ve never had before.”

THE MYSTERIES OF MENSTRUATION

While live birth defines mammals, including everything from whales to dogs to bats, there’s one thing that sets humans apart from most other species: menstruation. We’re part of an exclusive club that’s limited to old world primates, elephant shrews, and fruit bats. All other species remodel and reabsorb the endometrium, or uterine lining. So why do humans have to deal with the hassle of a period? Scientists aren’t quite sure. One theory is that the process protects us from abnormal pregnancies. The human gestation period is so long and requires so many biological resources that it’s better to reject all but the best candidates. And the reason we have periods is far from the only thing we don’t understand about menstruation.

“There is so much we don’t know,” says Hilary Critchley, OB/GYN and professor of reproductive sciences at the University of Edinburgh. “Not only why do we have normal periods, but particularly why does a woman have heavier periods?” Critchley and her colleagues published a paper that compiled years’ worth of studies in Human Reproduction Update in July 2015. They found far more questions than answers. Their research confirmed what is known: that a decline in progesterone triggers menstruation, and that the endometrial coagulation system plays a part in stopping the bleeding. But plenty of questions remain about the mechanics of the process.

Doctors don’t know what regulates inflammation during menstruation, what causes the bleeding to stop, or how the uterus repairs itself so quickly without creating any scar tissue. They also don’t understand the causes of diseases associated with menstruation, like polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis. Neither currently has a cure, and they afflict around 1 in 10 women. In the most extreme cases of endometriosis, women have no choice but to undergo hysterectomies.

“If you’re in the workforce, period problems can be really embarrassing and really difficult to deal with. This is where I see the unmet need for new treatments,” Critchley tells Mental Floss. “A woman now has 400 periods in a lifetime. A woman (100 years ago) had 40. If you’ve got more periods, you’ve got more opportunity for it to be a problem.” This increase in the number of periods by a factor of 10 in the past 100 years is due to contraception and improved nutrition. The downside is that's a lot more opportunity for menstruation to cause problems.

GROWING AN EXTRA ORGAN TO MAKE A BABY

Menstruation isn’t the only area of female reproductive health that has researchers scratching their heads. Perhaps even more confounding is the placenta, a transient organ created during pregnancy by the embryo.

“I’d say the placenta is probably the least studied and the least understood organ in the body,” says Catherine Spong, acting director of the National Institute of Child and Human Development. She oversees the Human Placenta Project (HPP), which aims to develop new tools to monitor the placenta throughout its development. “If you could understand how the placenta allows two genetically distinct entities not only to grow, but also thrive, the implications for enhancing our understanding of immunology and transplant medicine would be pretty remarkable.”

Stacy Zamudio, a recipient of a grant from the HPP and director of research at Hackensack University Medical Center, calls the placenta “the most wonderful organ ever.” Her research focuses on placenta accreta (when the placenta grows too deeply into the mother’s uterine wall and even outside organs).

“It breathes, it produces hormones, it produces immunologic factors that protect the baby against infection. It acts like a skin, a liver, a kidney, a lung—it does all the functions of the other organs in one organ,” Zamudio says.

The placenta achieves this by hooking into arteries in the uterus, essentially hijacking the mother’s body so the embryo can have a constant stream of nutrients and oxygen as it develops. When it’s functioning normally, the placenta ensures a positive outcome: healthy baby, healthy mother. But when things go wrong with the placenta, they quickly go from bad to worse.

The placenta can be under-invasive, meaning the connection to the mother’s blood isn’t strong enough. The baby stops developing because it’s not getting nutrients, and in the worst cases the mother can suffer from preeclampsia, which causes life-threateningly high blood pressure and can only be treated by immediate delivery of the baby. Or, as with the cases Zamudio studies, the placenta can be over-invasive, infiltrating the uterus and other organs beyond it like a cancer. Finally, in a complication known as placental abruption, the placenta can peel away from the uterus before delivery, removing the baby’s source of oxygen and nutrients and causing heavy bleeding in the mother.

Pregnancy can be a dangerous balancing act, and if doctors had better ways of monitoring the placenta’s development over the course of pregnancy, they might be able to prevent or avert the worst outcomes.

FROM WOMB TRANSPLANTS TO TRICORDERS

In October 2014, a baby born to a Swedish couple became an exciting example of the possible future of maternity—he was the first child ever born of a transplanted uterus. (The first pregnancy from a womb transplant, in Turkey, was terminated in 2013 when the fetus had no heartbeat.) The 36-year-old mother, who was herself born without a uterus, received a donation from a woman in her 60s, and had a frozen embryo successfully implanted in the transplanted organ. Although the child was born prematurely, he and the mother were otherwise healthy after the pregnancy. Since then, four more women who received uterus transplants from doctors at the University of Gothenburg have gotten pregnant.

The pioneering surgery is now spreading across the world. Doctors at Cleveland Clinic performed the first successful uterus transplant in the U.S. just last week. The 9-hour surgery was performed on a 26-year-old patient with uterine factor infertility (an irreversible condition affecting 3 to 5 percent of women that prevents pregnancy). If the patient heals and can become pregnant, the surgery could offer new hope to women who previously thought they were doomed to infertility.

Despite the enormous advances made in the last decades concerning women's health, many questions about the uterus remain unanswered. Scientists don’t know why the placenta sometimes grows too little or too much, or how it communicates with the rest of the organs in the mother’s body. They don’t know why some women have debilitating cramps during their periods that have been likened to the pain of having a heart attack. But with scientists around the globe investing time and resources into such questions, it might not be long before we have real answers and solutions to these problems.

"We're not that far away from the tricorder in Star Trek," Zamudio says, referring to developing technologies like nanomagnetics. "I'm hoping that I'll be alive long enough to see a doctor be able to wave the instrument over the woman's abdomen and tell me what the glucose level is in that body."