Russians Conquer Erzurum, Cameroon Falls

By Erik Sass

Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 225th installment in the series.

February 18, 1916: Russians Conquer Erzurum, Cameroon Falls

With one of the biggest battles in history delayed by a sudden blizzard on the Western Front, 2,500 miles to the east the Russian Caucasus Army was pressing their surprise attack on the Ottoman Third Army in arguably worse conditions, pursuing the retreating Turkish forces across rugged mountain terrain towards the ancient cities of Erzurum and Muş in Eastern Anatolia.

After defeating the Turks at the Battle of Koprukoy from January 10-19, 1916, the Russian Caucasus Army, about 165,000 strong, laid siege to the battered Ottoman Third Army, now probably numbering 50,000 men or less, while the Ottoman commander, Mahmut Kamil Paşa, hurried back from Constantinople – but it was already too late. On February 7 the Russians captured Hinis, south of Erzurum, cutting the defenders in the city off from potential reinforcements in Muş, which soon fell to the Russians.

On paper the Turkish defenses at Erzurum were formidable: surrounded by two rings of forts dominating strategic mountain passes, the main citadel was located in a plain on a high plateau and protected by over 200 pieces of artillery – but in reality the outnumbered Turks didn’t have nearly enough troops to man all these defenses.

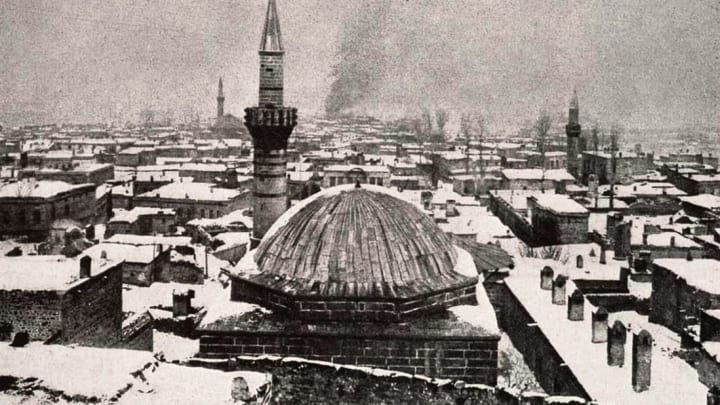

The Russian bombardment opened on February 11 (above, smoke rises on the outskirts of Erzurum) and by February 14 Russians had captured two forts and occupied the strategic heights above the city, extinguishing any hope the city could be held (below, Russian soldiers in front of captured Turkish artillery). The following day Kamil Paşa ordered the remaining forts evacuated, and on February 16 the Ottoman Third Army – now diminished to just 25,000 men – began evacuating the city itself. The road west, including to the strategic port city of Trabzon, now lay open to the Russians; to the south, the conquest of Muş opened the way to Bitlis.

The winter weather in the mountains continued to be a serious threat to both sides: in fact the Russians suffered almost as many casualties to frostbite as they did to combat (4,000 versus 5,000). A British correspondent, Philips Price, described the stark scene in the Russian positions outside Erzurum:

The sun was setting, and every living thing that stood above the snow could be seen for miles, silhouetted against the white. Long trains of camels were sailing up from the northeast to the sound of deep-toned bells. Little camps of round Asiatic tents clustered under some bare willow-trees beside a frozen stream. The smoke of fires rose up, and soldiers could be seen huddling around to keep themselves warm. Bunches of black objects dotted about the plain showed the existence of villages half-smothered in snow. A few black dots languidly moving round their outskirts proved to be the pariah dogs, the sole remaining inhabitants. They were fate and puffy. No wonder, for they had had plenty to eat lately. The sights we had seen earlier in the day, the half-eaten carcases of camels, and the torn bodies of men, had shown us that war means a rich harvest for the Asiatic pariah dog.

Price also described Russian Cossack units harassing the retreating Turks after they abandoned Erzurum:

As our wagons slowly wound up the narrow roads that lead across the chain, we became aware that we were in the rear of an advancing army. Immense quantities of stores and ammunition and columns of infantry reserves were on the road ahead of us, so our pace was slowed down to theirs. As we crossed the last neck of rising ground before sinking down into the Euphrates plain, we heard the rumble of artillery, and far in the distance, with the aid of glasses, we could make out detachments of retreating Turks fighting rear-guard actions. The dark lines moving like worms across the snow-fields were the pursuing Cossack columns.

Cameroon Falls to Allies

The war in Africa was conducted on a scale as small as the European war was large, at least in terms of manpower, as opposing forces of just a few hundred men pursued each other across vast, sparsely inhabited stretches of wilderness. However the outcome of these strange campaigns was never really in doubt: even at this small scale, the German colonial militias were hugely outnumbered by the Allied forces sent against them, and defeat was only a matter of time. German Togoland capitulated at the beginning of the war, in 1914, followed by German Southwest Africa (today Namibia) in July 1915.

On February 18, 1916, another German colony finally fell, with the surrender of the tiny German force holding out at the siege of Mora mountain in northern Kamerun (Cameroon). The German force, originally consisting of just over 200 mostly African native troops, had held out for an astonishing year and a half while surrounded by around 450 Allied troops (150 British, 300 French, mostly colonial troops from neighboring British Nigeria and French Central Africa).

In the first half of 1915 the German troops endured thirst and near-starvation, with small scouting units sneaking through Allied lines to forage for food. The Allies redoubled their efforts in September 1915, inflicting more casualties on the dwindling German force, but the latter were still able to repel repeated infantry assaults.

Meanwhile the rest of the colony had fallen to the Allies, as about 1,000 German soldiers, 6,000 native African soldiers, and 7,000 camp followers fled to neighboring Spanish Rio Muni, then sailing to the Spanish island of Fernando Po (technically in violation of Spanish neutrality, which clearly meant little by this time). With food once again running short and more Allied forces becoming available to join the siege, by early 1916 the German situation was getting desperate.

To bring the standoff to an end the British commander, Brigadier General Frederick Cunliffe, offered the German commander, Captain Ernst von Raben, generous terms of surrender: all the German Askaris (native troops) could return to their homes and the European officers would return to Europe for comfortable prisoner of war camps in Britain. Cunliffe also agreed to give Raben money to pay his loyal Askaris. On February 18, 1915, 155 German troops finally surrendered to the Allies (above, a British native soldier waves a flag of truce; below, British troops in Yaounde, the German capital of Kamerun).

After the war the British and French partitioned German Kamerun, with most of the territory going to form the new French colony of Cameroun, while a strip of territory along the old border went to British Nigeria (see map below; boundary disputes between Cameroon and Nigeria, centering on the oil-rich Bakassi peninsula, continued until 2006, and some Nigerian lawmakers rejected the agreement transferring the peninsula to Cameroon).

See the previous installment or all entries.