When Werner Herzog Ate His Own Shoe

By Jake Rossen

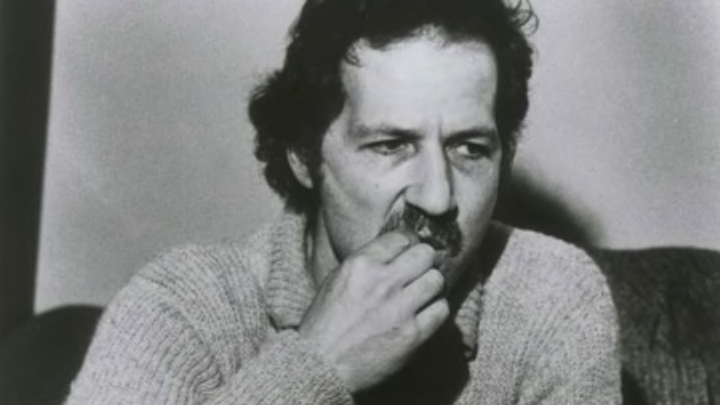

Werner Herzog could not understand Errol Morris. The German-born filmmaker had already made Aguirre, the Wrath of God and was infamous for his relentless approach to getting movies produced. To Herzog, lack of equipment was no excuse: borrow cameras if you can, steal them if you must.

In Morris, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, he saw a highly intelligent and ambitious young man who was too easily distracted. Morris was an accomplished cellist who gave up the instrument; he had conducted several interviews for a book on serial killers that he had also abandoned. He wanted to make a documentary film, but complained that raising financing would be problematic.

Herzog told him it was just an excuse. To antagonize Morris, he offered a wager. “I’ll eat the shoes I’m [now] wearing the day I see your film for the first time.” They were Clarks, made of leather and cut high over the ankle.

In spring 1979, at the Berkeley premiere of Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven, Herzog sat down and began to chew on his own left shoe.

Herzog and Morris had met at the Pacific Film Archive, a screening room and movie library, in the mid-1970s. Morris was enamored with Herzog, who made films on his terms; Herzog admired Morris’s abilities to extract information from interview subjects. The two visited serial killer Edmund Kemper in prison and once discussed plans to dig up killer Ed Gein’s mother in Wisconsin to see if Gein had desecrated her corpse. (Herzog showed up, shovel in hand; Morris did not.)

In the late 1970s, Morris completed work on his documentary feature, Gates of Heaven, about a pet cemetery and the grief-stricken owners of the recently departed. Herzog was busy with pre-production on a feature, Fitzcarraldo, when he received word from Pacific Film's Tom Luddy that Morris's movie was due to be screened at UC Berkeley’s theater in April 1979.

Luddy remembered the bet; Morris did not. Instead of being amused, Morris recalled feeling irritated that Herzog was going to go through with the stunt, believing it was drawing publicity away from the film. Herzog, for his part, argued that he would be good exposure for Gates of Heaven and might result in Morris landing a distributor.

On April 11, Herzog touched down in San Francisco and met with a colleague, Les Blank, who planned to document the result of his lost wager for a short film. (Titled Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, it was released the following year.) Herzog showed off the same Clarks he claimed he was wearing when he challenged Morris: the two headed for Berkeley’s Chez Panisse restaurant, where acclaimed chef Alice Waters was prepared to help the director make his footwear palatable.

The restaurant had been serving duck that day, and Herzog latched onto the idea of boiling the shoe in duck fat in an attempt to soften it. Before putting it in the pot, he stuffed it with garlic and added rosemary, onions, and Tabasco sauce. He tied the laces together in an attempt to capture the flavor and left it to marinate for five hours.

When Herzog carried the pot on stage before the premiere of the film, he announced that the duck fat solution had been a failure: instead of softening the leather, it had toughened it. The rubber sole was declared inedible, having melted off “like cheese on a pizza.”

As he interacted with the audience, Herzog began to snip off tiny pieces of the shoe with poultry shears, chewing what he could before washing it down with beer.

Herzog made a joke about the meal being no different from fast-food chicken and declared that his “clown” show was worthwhile if it inspired filmmakers to take the initiative. The action eventually moved back to the restaurant, where an increasingly inebriated Herzog continued to nibble on small portions. He vowed to save the right shoe in the event a major studio like Fox picked up Morris’s film.

Gates of Heaven did eventually receive a wide release, launching Morris’s career and eventually being named one of Roger Ebert’s favorite American films of all time. But an annoyed Morris wasn’t present for Herzog’s stunt. (The two eventually reconciled.)

In the years since, Herzog claims not to remember the taste of his shoe, the six beers having wiped his memory of the evening. But he’s never expressed any regret over the spectacle. “Anyway,” he told an interviewer, “there should be more shoe-eating.”