We’ve Been Seriously Underestimating the Number of Viruses on Earth

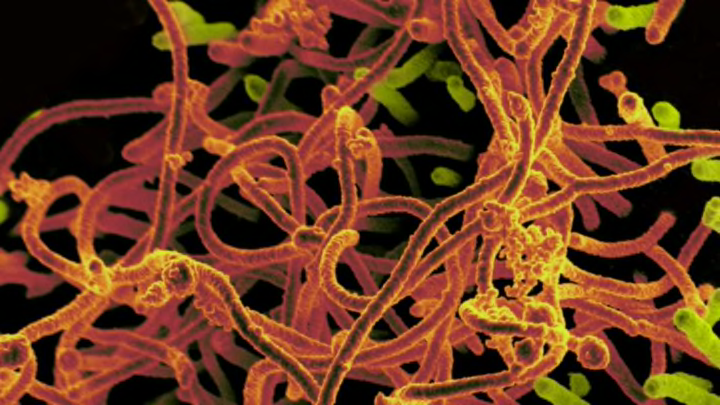

We don’t mean to alarm you, but there are viruses everywhere—and they have been tricky to categorize. (They're not all bad! We’re not even sure if they’re alive!) The most recent report, published August 17 in Nature, has found that there are exponentially more viruses on this planet than we ever believed.

Viruses’ slippery nature can also make them difficult to understand. Because they can’t reproduce outside of a living host, scientists have often relied upon those hosts as a starting point. They culture hosts and viruses in the lab and painstakingly monitor their interactions. But the massive computing power of modern technology has offered virologists another way.

Researchers from the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Joint Genome Institute created a new model for counting viruses. They tapped into the DOE’s Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD), which offers complete genetic data on tens of thousands of plants, animals, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. They were especially interested in metagenomes—that is, all of the genetic material in a sampled environment.

The team dug through 5 terabytes of metagenomic information from more than 3000 different environments, looking for viruses and their hosts, then compared their findings with the genetic codes of known species. The samples came from 10 different habitat types, including the ocean, the soil, thermal springs, plants, and the human body.

They found what amounts to a viral cornucopia. Those 3042 samples were home to at least 125,000 different viruses, one of which is the largest-known bacteriophage (bacteria-eating) virus ever seen. Half of the viruses could be sorted into family groups, and many of those groups were genetically unlike any viruses known today. The researchers say their findings multiply the number of known viruses in our planet's virome, or viral ecosystem, by a factor of 16.

The research also yielded some interesting insights about viruses’ hosts. Some researchers have argued that any cellular organism, including a bacterium, is susceptible to parasite infection. The new findings seem to support that hypothesis; not only did they double the number of known microbe phyla (groups) that can be infected, but they even identified viruses that can infect more than one phylum.

The team then mapped their findings, and saw that similar viruses tended to prefer similar types of habitats even when they occupied different parts of the globe. Perhaps most surprising of all, the researchers say, was discovering that unrelated people in different places can share very similar viral ecosystems.

Image credit: Paez-Espino et al., 2016. Nature

“Ultimately, large-scale computational exploration of uncharted viral sequence space will assist in addressing the remaining mysteries of viral ecology,” they write.

We can hope.

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.