What Long-Dead Bees Can Tell Us About Our Ancestors

To the dedicated detective, everything looks like a clue. Take this approximately 3-million-year-old bees’ nest, for example: Researchers say its very presence speaks volumes about the world in which our early ancestors lived. They published their report today, September 28, in the journal PLOS One.

The ancestor in question is Australopithecus africanus, a small hominid species with both human- and ape-like features that lived in modern-day South Africa. Au. africanus was little to begin with—adult males averaged around 4’6”, females 3’9”—but the first specimen ever found was littler yet. The Taung child, as it came to be known, was first unearthed in 1924, and represented the earliest human ancestor ever found in Africa. Archaeologists found a few more Au. africanus individuals over the next decade, and then the wellspring of remains dried up. We haven’t found any more Australopithecus there since.

But the absence of bodies isn’t the same thing as a dead end. Researchers have simply turned their attention to exploring the world of Australopithecus in other ways: namely, looking at the site itself, at its geology, environment, and all the other fossils found there.

When we think about fossils, we typically think about the remains of plants and animals. But the traces left behind by these organisms can become fossils too. These footprints, burrows, and nests are harder to pin down to a single species, so scientists classify them into groups called ichnogenera.

Fossilized burrows in the ichnogenus Celliforma were most likely made by prehistoric bees. Unlike the humming, social hives of honeybees, each flask-shaped Celliforma nest was dug out of the ground and occupied by a single bee.

These nests are somewhat rare, and they’ve never been seen before in Africa, so researchers were understandably pretty psyched when they found one in Au. africanus territory near the edge of the Kalahari desert.

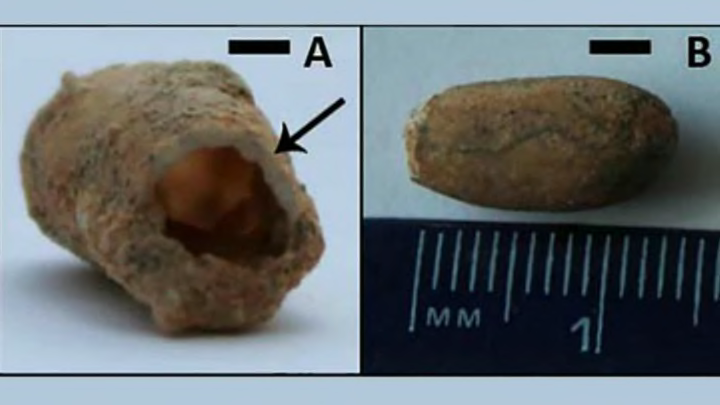

The nest was in great shape, given its age. The outside was covered with 25 small chambers, each of which would have housed a baby bee millions of years ago. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the entire nest revealed a complex system of tunnels and cells within, as well as traces of tiny plant parts that would have once lined its walls.

Parker et al. (2016)

The researchers say the nest’s overall structure is most similar to the homes of modern carder bees, which glaze the interior of their nests with a thin layer of clay, smooth it out with a wax-like substance, then add pieces of plants.

The nest’s structure and contents suggest that it was built in light, dry soil—findings that support previous studies, which hypothesized that Au. africanus may have lived in an arid, savannah-like environment.

"Insect traces are rarely considered in detail," the study authors conclude, "yet they could offer important palaeoenvironmental insights, with the potential to reveal valuable information about hominin palaeoecology."

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.