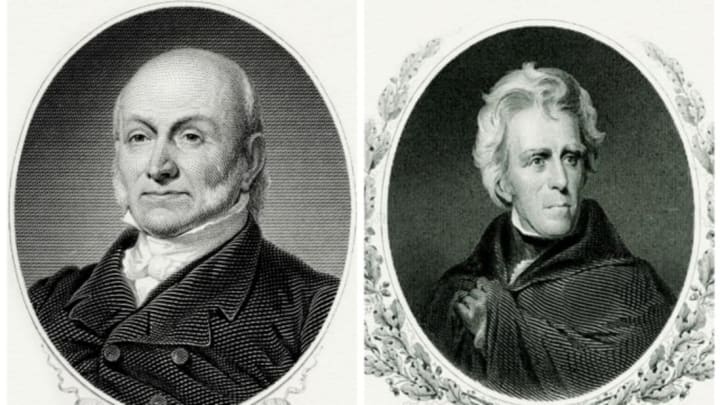

The Time Andrew Jackson Won the Vote but Lost the Presidency

In 1824, Andrew Jackson found himself in a confusing situation: He won both the popular vote and got the most votes in the electoral college, but lost the election anyway.

That year, there were four main contenders for president, all from the Democratic-Republican party: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of the Treasury William Harris Crawford, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, and Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson.

At the time, a candidate needed 131 electoral college votes in order to win the presidency. After all of the ballots were counted, Jackson had received 99 votes to John Quincy Adams’s 84. The remaining votes were split between Crawford and Clay—41 and 37 respectively.

Though Jackson clearly received the most votes—both popular and electoral—he didn’t reach that magic 131 number. Because no one did, the election was kicked to the House of Representatives. According to the 12th Amendment, which refined the process of voting for the president and vice president, the House could only consider the top three candidates, which meant Clay was out.

And that’s when things got interesting. Clay didn’t particularly care for John Quincy Adams, but we know the two of them met privately before the House voted. It’s since been alleged that the pair made what is now known as a “Corrupt Bargain”—Clay promised to work behind the scenes to get the House vote to go Adams’s way, and in return, Adams guaranteed Clay the Secretary of State position.

Both men denied making such a deal, but the proof may have been in the pudding. Clay began actively campaigning for Adams, working hard to turn his votes into votes for Adams. In the end, Adams carried 13 states, Jackson took seven, and Crawford four. As the results were announced, there was so much booing, hissing, and general uproar from the public galleries in the House that the Speaker of the House—Henry Clay—had them all thrown out.

Jackson eventually had his revenge, though. In the 1828 election, he handily defeated the incumbent John Quincy Adams, and served two terms to Adams’s one.