10 Facts About Ansel Adams

By Jake Rossen

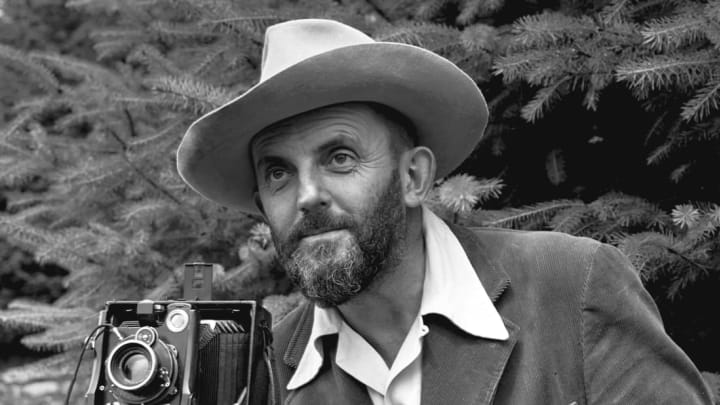

Famed photographer Ansel Adams drained the color from life to great effect. His black-and-white photographs of famous landscapes like Yosemite National Park have been seen by millions, reproduced on calendars and posters, and recognized by presidents as being crucial to conservation efforts. If you’re curious to learn more about Adams (who was born on this day in 1902), take a look at some of these lesser-known facts about both his life and his life’s work.

1. An earthquake broke his nose.

Born in San Francisco to Charles and Olive Adams on February 20, 1902, Ansel was just 4 years old when San Francisco was struck by the great earthquake of 1906. During an aftershock, he lost his balance and fell face-first into a garden wall, breaking his nose. The damage was so severe that it would become a remarkable feature of Ansel’s face. Between his nose—which caused him a lot of problems socially—and a disdain for the formalized education he was receiving, Adams eventually elected to be tutored at home by his father and aunt before he got a “legitimizing diploma” and graduated with an approximately eighth grade education.

2. He originally wanted to be a concert pianist.

Adams was a solitary kid, studying at home and wandering trails by himself. He began practicing the piano at the age of 12, and by 18, he decided he would make it a profession and began a path to becoming a concert pianist. Throughout the 1920s, however, Adams’s frequent visits to the Sierra Nevada region stirred an interest in photography. After contributing images to the Sierra Club newsletter and opening a one-man exhibition in 1928, he decided, in 1930, to make photography his full-time career.

3. A granite summit made him famous.

As he became more interested in photographic pursuits, Adams got assistance from Albert Bender, an art patron in San Francisco who told Adams that he would help him circulate a portfolio of his work. One of the last images needed to complete the sampler was of the Half Dome, a sheer granite summit in Yosemite that extends 5000 feet above the valley. In April 1927, Adams climbed to a rock cliff known as the Diving Board and managed to get the shot he wanted. The image, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, became one of his best-known works.

4. His work appeared on a coffee can.

Adams often agreed to commercial work in order to subsidize his more creative pursuits, trying to strike a balance between paying bills and garnering satisfaction from his environmental awareness ambitions. In 1969, the Hill Brothers Coffee Company licensed Winter Morning, Yosemite Valley for their 3-pound coffee tins. The containers can bring up to $1500 when they come up for auction.

5. He didn't shy away from critiques of World War II.

Though Adams is best known for his nature photography, the outbreak of World War II drew his eye to an entirely different topic. He photographed the interment camp at Manzanar, one of many such sites that detained Japanese-Americans, depicting their prejudiced treatment at the hands of the U.S. government while being forced to exist in war relocation centers. Adams donated the collection, which included more than 200 photographs, to the Library of Congress in 1965, writing that “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment ... All in all, I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use.”

6. He was presented with the Medal of Freedom.

Collectively, Adams’s art was a giant portrait of conservation efforts intended to reveal the beauty of national landmarks and the value in preserving them for future generations. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor awarded to civilians, to acknowledge his efforts on behalf of environmental causes. Carter dubbed Adams a “national institution.”

7. HE "mutilated" some of his own negatives.

In order to stir up interest for his Portfolio VI book collection in 1974, Adams purposely limited the number of copies available by advertising that no more reproductions could ever be struck from the original negatives—he had run them across a check canceling device, destroying them. Adams later regretted the decision, writing in his autobiography that “negatives should never be intentionally destroyed.”

8. He had problems with a couple of presidents.

Adams’s political views on environmental conservation were embedded in the fabric of his identity. When politicians didn’t agree, he had no problem butting heads. Adams refused to take a presidential portrait of Richard Nixon due to Nixon's reluctance to support public lands. After meeting Ronald Reagan in 1983, Adams expressed disinterest in any further communication, telling The Washington Post that the president had no “fundamental interest or knowledge in the environment.” An earlier exchange with Playboy was more cutting: “I hate Reagan,” Adams said.

9. He didn't see any financial rewards until late in life.

“Professional nature photographer” was not considered a lucrative vocation when Adams was devoted to his craft. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when an associate advised him to stop selling prints and focus on his book collections, that Adams became financially solvent.

10. He had too many photos to print.

When Adams died in 1984, curators of his extensive 40,000-plus photo archives marveled at the fact that the photographer never found time to print many images they considered to be masterpieces. Thousands of portraits and color photos were tucked in shoeboxes, with some later appearing in collections of his work. Adams, a perfectionist, insisted on developing and exposing prints himself. He had taken so many photos that there simply had not been enough hours in the day to process them all.