John James Audubon’s Made-Up Bulletproof Fish

Even legendary naturalists like to have their fun. John James Audubon is best known today for his bird paintings and descriptions, but in his heyday, Audubon studied pretty much every animal he could find, and piles of field drawings accumulated in his Kentucky home. It was these drawings that would later serve as the vehicle for Audubon’s best-known (and possibly only) practical joke.

As Allison Meier explains for Hyperallergic, the hijinks began in 1818 when Audubon welcomed fellow naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque into his home. Constantinople-born Rafinesque was an accomplished collector of specimens, a seasoned traveler, and an author. He was also—as historians tell it—pretty annoying.

Rafinesque had a passion for discovering new species. He dug enthusiastically into Audubon’s stacks of sketches and notes, exclaiming each time he encountered a species he’d never seen before.

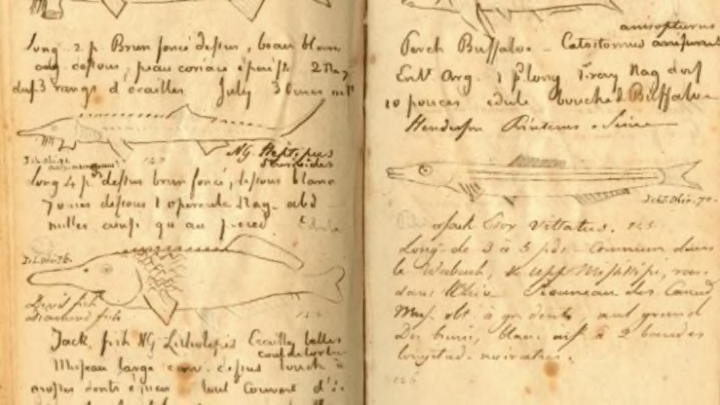

The travelling naturalist was staying with Audubon and his family for three weeks. At some point during that (possibly overlong) visit, Audubon decided to have a little fun at his guest’s expense. He slipped a variety of new drawings into the stacks. They looked like all the others, but they illustrated a fish species that did not exist. The phony field notes described an “Ohio red-eye” (Aplocentrus calliops), a “Flatnose Doublefin” (Dinectus truncates), and, most memorably, the “Devil-Jack Diamond fish” (Litholepsis adamantinus), which Audubon claimed was four to ten feet long and covered with bulletproof scales.

Rafinesque fell for the scam species hook, line, and sinker. Not only did he take Audubon at his word, but he would even go on to reproduce the drawings and ludicrous descriptions in his own field journals, citing them as fact. Still, as a man of conscience, Rafinesque did note that he had never seen most of these fish with his own eyes.

Image courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library, digitized by Smithsonian Institution Archives

It’s not known if Rafinesque ever discovered that he’d been had. But the prank was not without consequences. Nine years later, Audubon published his landmark book The Birds of America, which featured life-size paintings of 435 species. But five of those species could not be confirmed. By this time, word of Audubon’s fictional fish had reached certain scholars, and they wondered if his “mystery birds” were yet more fabrications. Audubon insisted that they weren’t, but his prank had cost him some credibility. Let’s hope Audubon was a little nicer to house guests after that.