Scientists Finally Identify the ‘Tully Monster’

It’s all right, everyone. We can breathe easy now, because scientists have finally identified the creature known as the Tully monster. The monster’s fossilized remains have puzzled paleontologists for nearly 60 years, but at last we have an answer. The researchers published their findings today in the journal Nature.

The first Tully monster remains were spotted in Illinois in 1958 by an amateur fossil collector named Francis Tully. What he found was so bizarre and hard to categorize that Tully settled on “monster.” Scientists determined that the Tully monster (now with the scientific name Tullimonstrum gregarium) had oozed or trod or swum the Earth 307 million years ago—240 million years before T. rex. As paleontologists continued to sweep Illinois’s Mazon Creek, where the first fossil was found, they found many, many more.

Holotype fossil. Image credit: © Paul Mayer, The Field Museum

Ghedoghedo via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

In 1989, T. gregarium became the state fossil of Illinois, despite the fact that nobody really knew what its was. Theories abounded, of course. Most assumed that the Tully monster was a soft-bodied invertebrate, but beyond that there was little agreement. Was it some kind of snail? A worm? A cuttlefish?

No, no, and no. A team of scientists from Chicago’s Field Museum, Yale, the American Museum of Natural History, and Argonne National Laboratory found that the monster was, in fact, a vertebrate: a really, really weird-looking jawless fish somewhat similar to modern lampreys.

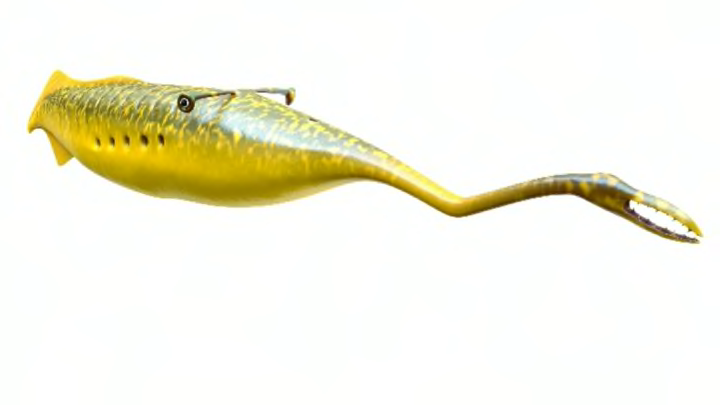

They came to this conclusion after reviewing digitized data and x-rays of more than 1200 T. gregarium fossils from the Field Museum’s collection. They determined that the creature was submarine-shaped, with fins, eyestalks, and an extra-long snoot ending in spiky teeth.

Co-authors Scott Lidgard and Paul Mayer both work at the Field Museum. “Mazon Creek is an amazing window into deep time,” Lidgard said in a press statement. “Only a tiny fraction of all the kinds of creatures that have ever existed become fossils, and it’s mostly hard parts like bone and shell that survive to tell the tale. Mazon Creek gives us an extraordinarily clear view of past life, preserving even insects, jellyfish, and the Tully monster. Research like this is a great way of learning where our world today comes from.”

“The Tully monster is a wonderful fossil that captures the imagination of every school kid,” Mayer added. “When I talk to school groups, I used to use the Tully monster as an example of a mystery that paleontologists have been trying to solve ever since it was discovered. Now I’ll have to change my talk and use it as an example that highlights the importance of how amateur paleontologists and researchers from different backgrounds can work together using new technologies and museum collections to solve a mystery.”