Scientists Develop Germ-Fighting Fake Mucus

We really don’t talk enough about the wonders of mucus. The goo produced by your nose, mouth, eyes, guts, and other parts is one of your greatest defenders, working hard to keep you safe in a germ-filled world. Now scientists have harnessed some of that power, creating a synthetic mucus that may help fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The research will be presented this week at the Experimental Biology 2017 meeting in Chicago.

Each of us produces about a gallon of mucus per day, enough to provide a thin coating over 2000 square feet of our innards. It’s a surprisingly versatile substance, for us and other animals. Last year, acoustic scientists reported that dolphins’ snot may be an essential ingredient in producing the clicks and whistles they use for echolocation. More recently, drug researchers found a powerful flu-fighting compound in the slime secreted by a tiny Indian frog.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Katharina Ribbeck is a tissue engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“I am so excited about mucus,” she said in a statement, “because I am convinced it can help us find new strategies for protecting us from infections, in particular those that relate to an overgrowth of harmful microbes.”

"Over millions of years, the mucus has evolved the ability to keep a number of these problematic pathogenic microbes in check,” she said, “preventing them from causing damage. But the mucus does not kill the microbes. Instead, it tames them."

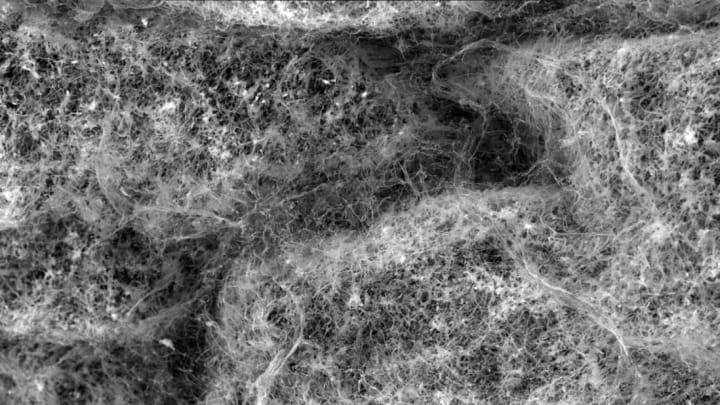

Ribbeck and her colleagues focused on strand-like mucus molecules called mucins (shown above), specifically one called MUC5B that’s found in our spit. They pitted MUC5B against two common oral bacteria: the cavity-causing Streptococcus mutans and the beneficial Streptococcus sanguinis. Left to their own devices, harmful S. mutans rapidly overwhelmed S. sanguinis and created a dangerous imbalance. But when the researchers introduced the bacteria to an artificial mucus solution containing MUC5B, the two species played nicely, living in relative harmony.

"We conclude from these findings that MUC5B may help prevent diseases such as dental caries [cavities] by reducing the potential that a single harmful species will dominate," said Ribbeck.