Scientists Grow Working Human Brain Circuits

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have successfully grown the first-ever working 3D brain circuits in a petri dish. Writing in the journal Nature, they say the network of living cells will allow us to study how the human brain develops.

Scientists have been culturing brain cells in the lab for some time now. But previous projects have produced only flat sheets of cells and tissue, which can’t really come close to recreating the three-dimensional conditions inside our heads. The Stanford researchers were especially interested in the way brain cells in a developing fetus can join up together to create networks.

“We’ve never been able to recapitulate these human-brain developmental events in a dish before,” senior author Sergiu Pasca, MD said in a statement.

Studying real-life pregnant women and their fetuses can also be ethically and technically tricky, which means there’s still a lot about our journey into the world that we don’t know.

“[This] process happens in the second half of pregnancy, so viewing it live is challenging,” Pasca said.

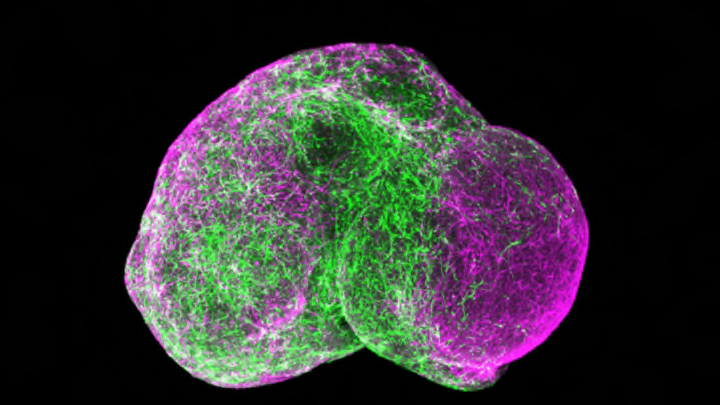

The latest project builds on earlier work from Pasca and his colleagues. In 2015, they devised a way to encourage pluripotent stem cells to grow, not into flat sheets, but into dense little spheres that can connect in three dimensions. The researchers used these spheres to grow two types of neurons, each found in a different region of the brain. Once the cells were functional, the researchers gently introduced the two groups to one another and watched to see what would happen.

Two cell groups, playing nice. Image credit: Pasca Lab at Stanford University

The results were extraordinary. Within three days, the two batches had begun reaching toward and networking with one another. Experiments on the new circuits showed that the still-growing cells were sending signals back and forth, strengthening connections between two areas of the brain. It was like watching a brain come into being.

“Our method of assembling and carefully characterizing neuronal circuits in a dish is opening up new windows through which we can view the normal development of the fetal human brain,” said Pasca. “More importantly, it will help us see how this goes awry in individual patients.”