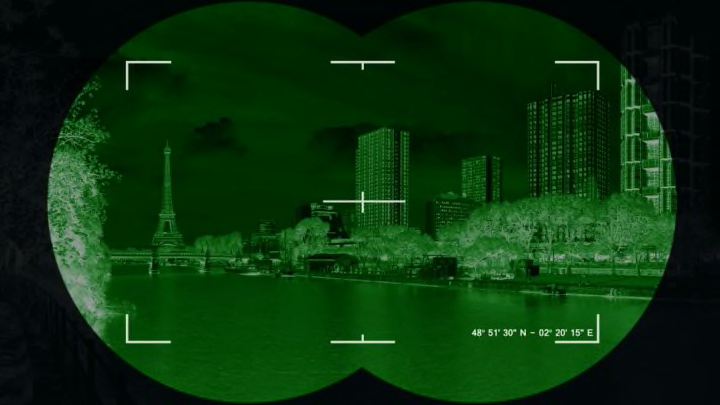

The characteristic green tint is by design, for a few reasons. First, device makers have experimented with a few different colors and found that the different shades that make up the monochrome night vision image are most accurately perceived and distinguished when they’re green. In other words, while the night vision images you’ve seen in Silence of the Lambs and Call of Duty might seem a little clunky, green presents a night vision device wearer with the most accurate and user-friendly picture possible. What’s more, because the eye is most sensitive to light wavelengths near 555 nanometers - that is, green - the display can be a little dimmer, which conserves battery power.

Who Invented Night Vision?

The first practical night vision devices were developed in Germany in the mid-1930s and were used by both German tanks and infantry during World War II. U.S. Military scientists had simultaneously developed their own night vision devices that first saw use during WWII and the Korean War.

These “Generation 0” devices used active infrared to brighten up a scene. Soldiers carried an IR illuminator to shoot a beam of near-infrared light that then reflected off objects and bounced back to the lens of their scope and created a visible image of what they were looking at. The illuminators used by the German Nachtjägers, or "night hunters", were about the size of dinner plates and required a large power supply carried on the soldier’s back.

The technology made huge leaps in the following decades, and by the time the U.S. entered the Vietnam War, many troops were outfitted with passive "starlight scopes" that used image-intensifying tubes to amplify available ambient light (usually from the moon and stars, hence the name) and produce an electronic image of a dark area.

This “Generation 1” technology is still around today in the more budget-friendly consumer-grade night vision devices. Military and police forces have upgraded to successive generations of tech with new improvements over the years, but image intensifying night vision - there’s also another flavor, thermal imaging, but image intensification is almost always the kind you see in movies and games - still works on the same basic principles as these early models.

I Can See Clearly Now

The lens or lenses at the end of a night vision scope or pair of goggles gather available light, including some from the lower spectrum of invisible infrared, and focus it on a photocathode on the device’s image intensifier tube, which transforms the photons, or light particles, into electrons.

As the electrons move through the tube, they flow through a microchannel plate, which is a disc with millions of tiny holes, or microchannels, in it. As the electrons strike electrodes on the microchannels, bursts of voltage cause the motion of electrons to increase rapidly, forming a dense clouds of electrons that intensifies the original image.

At the far end of the tube, the electrons hit a screen coated with a phosphor, which is a substance that radiates visible light after being energized. (We talked about phosphors in relation to glow-in-the-dark toys a while ago.) The energy from the electrons excites the phosphor which converts the electrons back into photons. These are in the same alignment as the photons that originally entered the tube, and form the greenish image on the screen inside the viewing lens of the device.