By Brittany Shoot

Betty Friedan was always cold. Cooped up in a rented stone house, the onetime newspaper reporter wore gloves at her typewriter, laboring over freelance articles in the quiet moments she could catch between tending to her two grade-school boys.

Her husband, Carl, was more than unsupportive—he was abusive, a cheat who flew into a rage whenever dinner was delayed. But Friedan, who was pregnant with their third child, knew that escaping the marriage would be difficult. Cut off from Manhattan and even from the nearest library, the freelance work she attracted didn’t pay well enough to make leaving an option. Mostly, she wrote for other reasons. Once a brilliant academic with a promising career, Friedan was stuck in housewife hell, bored out of her mind. She needed the escape.

In 1957, Friedan picked up an assignment from her college alumni magazine. It seemed fun. What she didn’t know was that the project would not only make her a household name—it would change the fate of American women.

"Just Be A Woman"

Born and raised in Peoria, Ill., Bettye Goldstein was a gifted student. She skipped second grade and eventually graduated with honors from Smith College, where she was an outspoken war critic and the editor in chief of the school newspaper. From there, her academic dreams took her to the University of California, Berkeley, where she studied under the renowned developmental psychologist Erik Erikson.

But even in the Bay Area’s liberal atmosphere, the pressure to conform to the era’s strict gender roles was palpable. Threatened by her success, Friedan’s boyfriend pushed her to turn down a prestigious science fellowship. As she’d later write in her autobiography, Life So Far, “I had given up any idea of a ‘career’, I would ‘just be a woman.’ ” Friedan abandoned her academic pursuits and took a newspaper job. But as her relationship with her boyfriend fizzled, Friedan’s love of reporting grew. When a colleague at UE News, the labor paper she was working for, set her up with his childhood friend, theater director Carl Friedan, they fell for each other. The couple married in 1947 and settled in New York City’s Greenwich Village.

It wasn’t long before the marriage soured. Betty kept up with household chores. She got pregnant. But nothing she did was good enough for Carl. She managed to finagle more than a year of maternity leave from her job after giving birth, but when she became pregnant again two years later, the union refused her additional leave. Instead, she was fired on the spot.

Meanwhile, the Friedans needed more space for their expanding family. They rented a stone barn–turned-house in Rockland County, 30 miles outside Manhattan. Shortly after their move, Carl became abusive. Isolated in the suburbs, Betty continued to squeeze in time for freelance work. As tension escalated, Betty stood her ground—if she was going to free herself from her husband, she’d need to earn more money.

With her 15-year college reunion approaching, Friedan was asked to conduct a survey of her Smith classmates. How had her fellow alumnae used their education? How satisfied were they with their lives? Collaborating with two friends, she crafted open-ended questions to elicit honest reactions from the more than 200 women to whom she sent surveys.

Friedan hoped the data might refute the findings in Ferdinand Lundberg and Dr. Marynia Farnham’s popular book Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, which made arguments like “The more educated the woman is, the greater chance there is of sexual disorder.” She knew education didn’t cause women’s sexual dysfunction, but how could she prove it?

As the completed surveys poured in, Friedan got her answer: The forms were filled with heartbreak and honesty. Women from all over the country confided the abject misery of their everyday lives, and the answers betrayed widespread feelings of resentment and isolation. Many women said they were undergoing psychoanalysis but said the treatments were only making their symptoms worse. Most male doctors were telling their female patients that the complaints were unwarranted or expected. Indeed, Lundberg and Farnham considered these complaints part of “a deep illness that encouraged women to assume the male traits of aggression, dominance, independence, and power.” Many doctors even urged patients to dive deeper into domesticity and to more fully embrace chores as a source of self-actualization. And yet, in their answers, none of the women extolled the virtues of vacuuming.

As Friedan read the reports, she thought about the ads that bombarded women on a daily basis: Be a supportive wife! Cook better meals! Scrub that tub! The messaging in women’s magazines was as biased as the doctors’. No wonder women felt trapped. Each was convinced that she was the only woman in the world who couldn’t find joy hiding beneath a stack of dirty dishes.

Armed with the survey results and her own media analysis, Friedan headed to Smith for the 1957 reunion. There, she planned to report her findings and speak in-depth with her former classmates about their collective ennui. But she was startled by the scene on campus: None of the current students she spoke with seemed keen to pursue interests or careers outside of suburbia. Perhaps they were buying into the arguments that magazines like Look were promoting at the time, stating that the modern housewife “marries younger than ever, bears more babies, looks and acts more feminine than the emancipated girl of the Twenties or Thirties.” The young women at Smith seemed more accepting of “their place” than when Friedan had graduated, a decade and a half earlier.

Place Holders

It was clear to Friedan that she had uncovered a major crisis facing middle-class American women, but you wouldn’t have known it from the reaction she received. Academics were skeptical and outright dismissive of her survey results. Magazine editors (most of whom were men) were uninterested in challenging the status quo—or sacrificing advertising revenue for the sake of a story. A handful of editors initially bought her pitches, only to deem the finished pieces too scandalous to publish. At Ladies’ Home Journal, editors reframed one of her articles to say the exact opposite of what Friedan had found, so she killed the story.

Friedan soldiered on. She conducted more interviews with alumni groups and students at other schools, neighbors, counselors, and doctors. She published where she could. Eventually, she persuaded Good Housekeeping to give her a platform by agreeing to play by its rules: Every column had to be presented with an optimistic slant. But as she continued to write, it became clear that only a book could adequately describe “the problem that [had] no name.”

In late 1957, Friedan managed to land a $3000 book advance from W. W. Norton. She hired a baby-sitter three days a week and annexed a desk in the New York Public Library’s Allen Room, assuming the book would take a year to complete. She couldn’t have predicted how long her manuscript would hold her hostage.

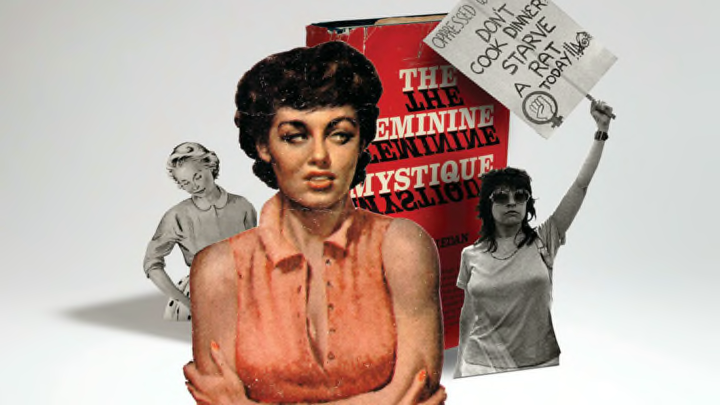

Five years later, her dogged determination paid off. In 1963, The Feminine Mystique, the now-classic treatise on the pervasive unhappiness of American housewives, made its debut on the New York Times bestseller list. It was the definition of irony. The writer who previously couldn’t publish an article had a book that kept falling off the bestseller list because printers couldn’t keep up with demand. But what was it about the book that made it so compelling? It’s hard to see now, but The Feminine Mystique came out well before psychology was a hip way of examining social phenomena. And even though Friedan leaned heavily on academic research, hers was the first popular examination of women’s depressing post-WWII private lives. Friedan forced America to confront a problem it had all too happily ignored, and, as the New York Times put it, “the portrait she painted was chilling.” The book turned Friedan into an instant celebrity. She went on a nationwide publicity tour, appearing in televised press conferences and doing talk shows. But what the camera didn’t catch was all the heavy makeup Friedan wore to conceal her bruises and black eyes. Life at home had not gotten easier.

Leading the Revolution

Buoyed by her success, Friedan moved back to Manhattan and distanced herself from her husband. Her move coincided with a larger cultural shift, as the women’s movement began to coalesce around the country. Focusing on many of the issues raised in The Feminine Mystique, including sex discrimination, pay equity, and reproductive rights, second-wave feminists won major battles in courtrooms and offices over the next several decades. Sexual discrimination in the workplace was outlawed. Title IX was passed to ensure that girls and women would not be excluded from school athletic programs. Marital rape became a punishable crime. Domestic violence shelters were established for the first time. Contraceptives were made widely available. Abortion was legalized in the United States. As second-wave leaders bulldozed their way through the 1970s, women were finally allowed to sit on courtroom juries in all 50 states, to establish credit without relying on a male relative, and the enlistment qualifications for the Armed Forces became the same for men and women.

Friedan’s leadership was vital in the transformative years that followed her book’s publication. In 1966, she helped found the National Organization for Women (NOW) and campaigned vigorously for Congress to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. And in 1969, a year history remembers as explosive and pop culture considers transcendent, Betty Friedan finally took her own words to heart—freeing herself from her loveless and abusive marriage.

In the ensuing years, Friedan remained involved in the women’s rights movement. She led the 50,000-person Women’s Strike for Equality in 1970. In the following decades, she helped found other notable women’s rights organizations, including the National Women’s Political Caucus. She wrote five more books. And by 2000, The Feminine Mystique had sold more than three million copies and been translated into numerous languages.

When Betty Friedan passed away on her 85th birthday, she was eulogized by NOW cofounder Muriel Fox, who said, “I truly believe that Betty Friedan was the most influential woman, not only of the 20th century, but of the second millennium.” Friedan had started a revolution by asking her friends and contemporaries the simple question no one had been bold enough to ask: Are you happy? And as she worked to answer the question for herself, she freed generations of women to come.

This article originally appeared in mental_floss magazine in our ongoing "101 Masterpieces" series. You can get a free issue here.