As any toddler chasing pigeons in the park knows, it’s not hard to figure out which birds can fly and which can’t. Sorting the flighted from the flightless is a little harder when those birds are dead—and even harder when they’re extinct. Now one fossil expert has developed a system that may help. He published his findings in The Auk: Ornithological Advances.

Junya Watanabe studies paleontology, evolutionary biology, geology, and mineralogy at Kyoto University. His research into the evolutionary history of birds has brought him up close with the anatids, a large family that includes ducks, geese, and swans. Today, most of these birds are happily flapping around, but that may not have always been the case.

Experts have found more than 15 fossilized anatid species that would have been unable to fly. We think. We’re not sure, because until now, we haven’t really had a good way of sussing out what flying looks like in animals that have been gone for millions of years.

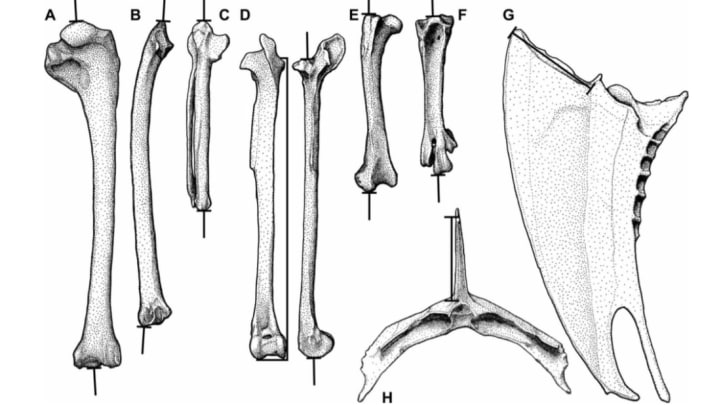

To look back into the past, Watanabe started in the present. He took precise measurements of 787 different modern anatids from 103 different species—some volant (flighted), some flightless—focusing on their legs, wings, and breastbones. Then he fed those stats into an algorithm that compared the proportions of each bird’s body with its flying ability.

The results showed physically tiny but evolutionarily significant differences between the species that could fly and those that couldn’t. Like the doomed dodos of yore, today’s flightless birds generally have chunkier legs and smaller wings than their airborne cousins.

By using the same algorithm on 16 species of fossilized anatids, Watanabe could easily spot which birds might have flown, long ago. His results confirmed other scientists’ suspicions about birds like Ptaiochen pao, whose name derives from the Greek and Hawaiian words for “destroyed stumbling goose.”

Helen James is curator of birds at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. She said Watanabe’s new system will be especially helpful in cases where only part of a fossilized bird has been found.

“Other researchers will appreciate that he offers a way to assess limb proportions even in fossil species where the bones of individual birds have become disassociated from each other,” she said in a statement. “Disassociation of skeletons in fossil sites has been a persistent barrier to these types of sophisticated statistical analyses, and Dr. Watanabe has taken an important step towards overcoming that problem.”