Typically, pets—not people—are microchipped. But as NBC News reports, one Wisconsin-based company plans to become the first business in the country to offer the tiny implants to its employees.

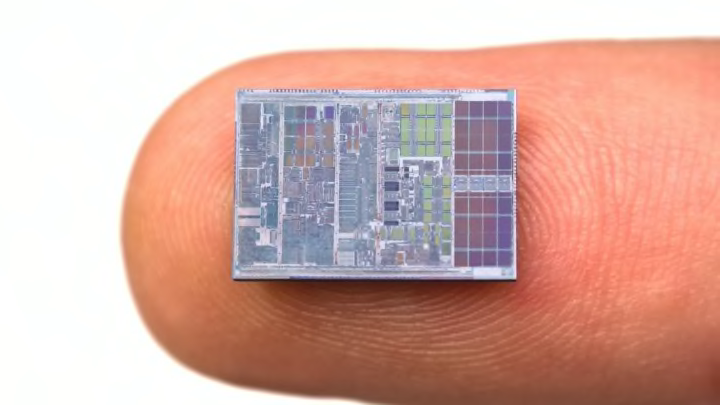

Three Square Market (32M), a software design firm in River Falls, Wisconsin, will begin providing the chips starting August 1. The rice-sized implants—which cost around $300 each—will be implanted in the hands of staffers between the thumb and the forefinger, and will allow them to purchase vending-machine snacks, open secured doors, or log into their computers with the wave of a hand. The company says the chips are optional.

32M is partnering with Swedish-based BioHax International to install the chips, which were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2004. The chips utilize electromagnetic fields to identify electronically stored data, and near-field communications, a technology that's used in contactless credit cards.

Fifty company members—including CEO Todd Westby—are expected to volunteer to receive the implants, according to a company statement. The company will foot the bill for the implants.

32M's microchipping program may sound unconventional, but the company—which owns machines that can use microchips—says it's simply riding the wave of the future.

"We see chip technology as the next evolution in payment systems, much like micro markets have steadily replaced vending machines," 32M's Westby said in the statement. "As a leader in micro market technology, it is important that 32M continues leading the way with advancements such as chip implants."

As microchipping becomes more common, Westby added, people will use the technology to shop, travel, and ride public transit.

The company says the chips are easily removable and can't be hacked or used to track recipients. However, some experts have argued the technology is an invasion of privacy, and that it could lead to heightened employee scrutiny.

"If most employees agree, it may become a workplace expectation," Vincent Conitzer, a computer science professor at Duke University, told NBC News. "Then, the next iteration of the technology allows some additional tracking functionality. And so it goes until employees are expected to implant something that allows them to be constantly monitored, even outside of work."

[h/t NBC News]