The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 89th installment in the series.

October 18-20, 1913: Serbs Back Down, But Kaiser Warns of Coming Race War

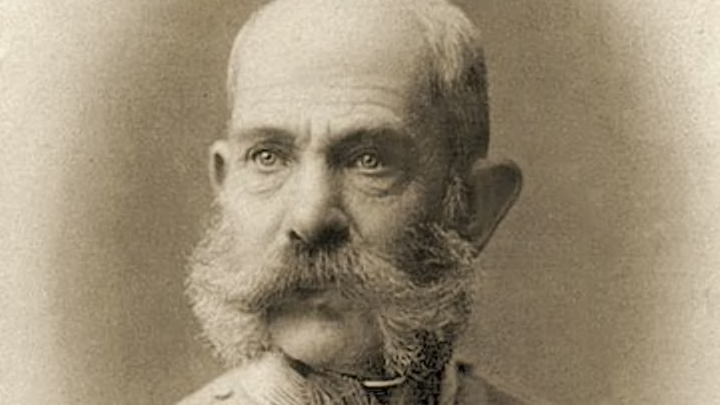

In October 1913, Franz Josef (top)—Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, Croatia, Galicia and Lodomeria, and Grand Duke of Krakow—was 83 years old and no longer in the best of health. The elderly monarch understandably hoped to live out his twilight years in peace, enjoying the company of his longtime companion (and perhaps mistress) the beautiful actress Katharina von Schratt, taking the air at the resort town of Bad Ischl or tea at the imperial palace of Schönbrunn in Vienna.

But Franz Josef was also a dutiful sovereign, motivated by feelings of responsibility to his subjects and the ancient house of Hapsburg to preserve and pass on his imperial inheritance intact. This meant seeing off various internal and external dangers, many of them linked, including nationalist movements among Austria-Hungary’s many minority populations and military threats from Russia and Italy—Great Power rivals who hoped to dismember the Empire and annex bordering territories.

What’s more, it was widely feared that Russia was encouraging its Balkan client state, Serbia, to trigger the Empire’s final crackup by stirring up dissent among its southern Slav populations; these fears were only heightened by Serbia’s expansion in the Balkan Wars and its continued meddling in the new nation of Albania, culminating in an invasion in September 1913. By openly defying Austria-Hungary, Serbia threatened to diminish the Empire’s prestige and even call into question its status as a Great Power.

All this was daunting enough, but Franz Josef’s task was further complicated by differences of opinion among his top officials and advisors. On one hand, chief of staff Conrad von Hötzendorf argued that Serbia indeed posed an existential threat to Austria-Hungary, which could only be ended by war, and by October 1913, the bellicose chief of staff had also persuaded Franz Josef’s foreign minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold, that Serbia had to be dealt with militarily; in their view, the Serbian invasion of Albania offered an ideal opportunity to settle accounts. Opposing Conrad was the heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who warned that attacking Serbia would bring Austria-Hungary into conflict with Russia, with potentially disastrous consequences.

But in the authoritarian Dual Monarchy the ultimate decision lay with Franz Josef. After initially siding with Franz Ferdinand, in mid-October the Emperor, doubtless dismayed by Belgrade’s defiant responses to several “friendly warnings” from Berchtold, decided to split the difference: Austria-Hungary would once again threaten to mobilize its troops against Serbia if the latter didn’t withdraw its troops from Albania immediately. Hopefully Serbia would comply, resolving the problem without war—but at the end of the day the old Emperor was ready to fight to protect his Empire’s interests.

On October 18, 1913, Berchtold sent a note to the Serbian government in Belgrade stating: “It is indispensable in the eyes of the Imperial and Royal government that the Serbian government shall proceed to the immediate recall of the troops… who… occupy territories forming part of Albania… Failing this, the Imperial and Royal government will to its great regret find itself compelled to have recourse to the appropriate means to assure the fulfillment of its demand.” He gave the Serbs one week to comply.

The Serbs, who faced more rebellions in Macedonia as well as continuing hostility from Bulgaria, caved almost immediately: On October 20, the Serbian ambassador to Vienna, Jovan Jovanović, promised Berchtold that the Serbian armies were being withdrawn behind the borders agreed at the Conference of London, and on October 25 Belgrade followed up with a second note announcing that the withdrawal was complete. Yet another Balkan crisis had been resolved peacefully.

But several unfortunate precedents had been set. For one thing, while Berchtold carefully lined up support from Austria-Hungary’s German ally, he didn’t consult with the other Great Powers before delivering the ultimatum. This meant Britain, France, Italy, and Russia never had a chance to intervene, for example by warning Serbia to withdraw or persuading Austria-Hungary to moderate its stance, as Italy had in the crisis of July 1913. Because everything worked out, the other Great Powers didn’t protest (too much) and Berchtold drew the conclusion that Austria-Hungary could go it alone in the Balkans, dealing with Serbia one-on-one without interference from the other Great Powers. In July 1914 this assumption would prove sadly mistaken.

Meanwhile, Germany’s leaders—already paranoid about being “encircled” by France, Russia, and Britain—feared losing their only ally, as the rise of Slavic nationalism threatened Austria-Hungary with dissolution. The only remedy for Serbian defiance, they felt, was war. On October 18, 1913, Kaiser Wilhelm II told Conrad, who was visiting Germany for the centennial celebration of Napoleon’s defeat at Leipzig: “I go with you. The other [Powers] are not prepared, they will not do anything about it. In a few days you will be in Belgrade. I was always a supporter of peace, but there are limits.”

As always, Germany’s leaders were haunted by anxiety about a looming “racial war” between Teutons and Slavs. Meeting with Berchtold during a visit to Vienna on October 26, Wilhelm shared his fear about the “powerful forward surge of the Slavs,” warning that “War between East and West was in the long run inevitable.” He elaborated: “The Slavs are born not to rule but to obey,” and if Serbia didn’t comply with Vienna’s demands, “Belgrade shall be bombarded and occupied until the will of His Majesty [Franz Josef] has been carried out. And you can be sure that I will back you and am ready to draw the saber any time your action makes it necessary.”

See the previous installment or all entries.