Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 303rd installment in the series. Read an overview of the war to date here.

MARCH 3, 1918: THE TREATY OF BREST-LITOVSK

After seizing power in November 1917, Bolshevik leaders including Lenin, Kamenev, and Zinoviev made it a top priority to end the war with the Central Powers, fulfilling one of the party’s key political promises (especially for millions of Russian soldiers, their most important constituency). But even these cynical apparatchiks, who claimed to harbor no illusionary nationalist sentiments, found that making peace was easier said than done.

Bolshevik negotiators first sat down with their opposite numbers at Brest-Litovsk during an armistice declared in December 1917, but were just as reluctant as the previous, short-lived republic to give up the huge chunks of territory demanded by Germany and its allies as the price of peace. Instead lead negotiator Trotsky, who opposed major territorial concessions, proclaimed his slogan “no war, no peace,” signaling his plan to use equivocation and delay to drag out negotiations until the Central Powers either agreed to compromise or, hopefully, succumbed to the worldwide communist revolution the Bolsheviks were sure was imminent.

However, German chief strategist Erich Ludendorff was in no position to dally, as he urgently needed to free up around a million troops for his planned spring offensive on the Western Front, aiming to defeat Britain and France before American troops began to arrive in substantial numbers. After signing separate peace treaties with Ukraine, the Baltic states, and Finland, in February 1918 the impatient Germans reopened the offensive against the dissolving Russian Army, brushing aside what few pockets of resistance remained and threatening to take even more territory than they had demanded in peace negotiations—and quite possibly toppling the Soviet regime while they were at it.

Realizing they now faced an existential threat, Lenin dismissed the objections of Bolshevik colleagues including Trotsky and Bukharin and their allies in the Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SR), arguing that their main goal had to be consolidating power in Russia, even if it meant giving up huge amounts of territory to the Central Powers. With Petrograd itself now under threat, in late February Lenin finally carried the day with a majority vote in the Bolshevik central committee (albeit by the thinnest of margins).

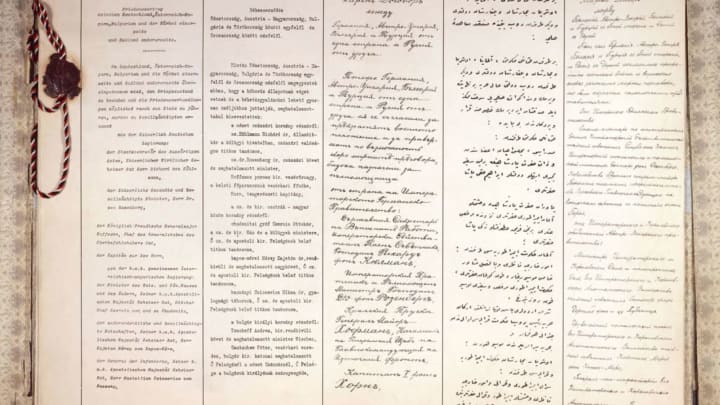

The result was the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed on March 3, 1918 in the city of the same name—one of the most punitive peace agreements in history, in which the Russians gave up Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, the latter divided into Courland and Livonia (top, the treaty translated into five different languages). Supposedly independent, all these new nations actually became German satellite states, as reflected in the fact that several “invited” Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II to assume the throne in a “personal union.”

Brest-Litovsk also rewarded Germany’s allies, though more modestly: Austria-Hungary received part of Ukraine and a guarantee of Ukrainian food supplies, staving off starvation in the Dual Monarchy at least temporarily, while in the Caucasus the Ottoman Empire won back the lost province of Kars, Batum and Ardahan. The Turks also helped themselves to Azerbaijan, giving the Ottoman Empire access via the Caspian Sea to the Turkic homeland in Russia’s former Central Asian provinces, another step toward fulfilling Enver Pasha’s dream of “Pan-Turanism,” or reuniting the Turkic peoples under Ottoman leadership. The Turks immediately set about occupying the ceded areas and other territory as well, soon spelling the end of the short-lived Transcaucasian Federation, which had refused to recognize the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. However, the Turks and Germans couldn’t agree who would get Georgia (so it went to the stronger Germans, who took Crimea and sent troops to occupy Georgia via the Black Sea in May-June 1918).

The treaty was a body blow for Russia, as the Central Powers intended, marginalizing and isolating the vast eastern realm from the rest of Europe and forcing it back on its sparsely populated Siberian hinterland. Among other losses, the ceded territories included over a quarter of the Russian Empire’s prewar population, half of its industrial production, and almost 90 percent of its active coalmines, as well as vital rail hubs and the Ukrainian breadbasket, one of the most fertile agricultural areas on Earth. In fact, the economic clauses of the treaty allowed German business interests to take over much of the Russian economy’s private sector and exempted them from the Bolsheviks’ sweeping

“nationalization” of Russian industry and commerce.

Unsurprisingly, the humiliating treaty was deeply unpopular in Russia, as attested by the fact that none of the Bolshevik leadership wanted to accept responsibility for it—Trotsky gave up his position as foreign minister to avoid signing it—as well as the decision by the Bolsheviks’ Left SR allies to resign from the Sovnarkom, the Soviet governing body, in protest. However, the Russian Army had basically ceased to exist while Allied offers to help the Bolsheviks resurrect the Eastern Front, perhaps with the help of freed Czech POWs in the Czech Legion, were too little, too late, so there was no one to resist the steady advance of the Central Powers’ forces into the ceded areas.

The treaty, which made Russia into a German client state and freed the Germans to focus on the Western Front, marked the final rupture between the Allies and Lenin’s Bolsheviks, who had already alienated France and Britain by repudiating around $6.5 billion of foreign debt accumulated by the former Tsarist regime as well as the Provisional Government and the Republic. The Bolsheviks, who renamed themselves the Communist Party on March 8, deepened the rift with propaganda and financial support for revolutionary subversion around the world, inciting soldiers to mutiny and encouraging local communist movements to overthrow the governments of the Allies and Central Powers alike (the Germans were particularly incensed that Bolshevik agitation continued uninterrupted despite the peace treaty).

For their part the Bolsheviks still distrusted German intentions, fearing the erstwhile foe might yet decide to topple the Soviet regime, which was, after all, openly plotting revolution in Germany. Thus on March 9, 1918 the Bolsheviks relocated the Soviet capital from vulnerable Petrograd to more distant Moscow, the medieval seat of Russian power, symbolically undoing Peter the Great’s mission to make Russia part of Europe along the way.

Like the rest of Russia Moscow was in the grips of chaos, but the Bolsheviks, safe behind the massive stone walls of the Kremlin, didn’t seem to mind, according to Pitrim Sorokin, a moderate socialist politician who described conditions in the new (old) capital:

"Throngs of refugees pouring into the town, Bolshevist officials trying to force communist doctrines on people who abhor them, peasants illegally bringing in and selling food and bread, and thereby saving the population from starvation, wrangling politicians and intellectuals, all these, together with the excited masses, give the impression of a furiously boiling pot. Many houses have been burned, many more damaged, many walls marked with bullets and bombs … Something had to be done to stay the hand of destruction, and quickly, for the morale of the populace was beginning to break down. Crazed with hunger, peasants and workers had already begun to strike, riot, and plunder. The Bolsheviki did nothing to restore peace."

In March, Sorokin and his wife tried to leave Moscow for a quieter town on the Volga, but met a typical scene that has come to symbolize the chaos of the Russian Civil War:

"At the station nobody could tell us when the train would start, but a huge crowd was waiting to rush it as soon as it arrived. After seven hours it rolled into the station, and then ensued a spectacle quite indescribable. The whole enormous crowd rushed madly forward, jamming, pressing, fighting, shrieking, climbing one man on top of another, and finally seizing places, in the train, on top of the wagons, on the platforms between wagons, and even on the brake beams underneath. As for my wife and me, we got no places at all, but were obliged to go back to our lodgings."

Conditions elsewhere were little better and often much worse, as the Bolsheviks and their White foes together unleashed a reign of terror against enemies real and imagined across Russia. The Bolshevik regime’s campaign of mass murder was excused by emergency decrees originally issued during the renewed German offensive, ordering Red Guards and the new cheka secret police to execute suspected enemy agents on the spot without trial, let alone a right of appeal.

Although the Red Terror didn’t officially begin until September 1918, mass executions were already commonplace by the spring of that year; ultimately the communist regime would execute around 200,000 alleged traitors, former Tsarist officials, and “class enemies” before the terror ended in 1920. The female soldier Maria Bochkareva, better known as Yashka, who narrowly escaped execution in early 1918, described one killing field where the Bolsheviks had murdered scores of political opponents and other undesirables:

"We were led out from the car, all of us in our undergarments. A few hundred feet away was the field of slaughter. There were hundreds upon hundreds of human bodies heaped there … We were surrounded and taken toward a slight elevation of ground, and place in a line with our backs toward the hill. There were corpses behind us, in front of us, to our left, to our right, at our very feet. There were at least a thousand of them. The scene was a horror of horrors. We were suffocated by the poisonous stench. The executioners did not seem to mind so much. They were used to it."

On this occasion Bochkareva was saved by a mid-ranking communist official who pulled her out of the lineup at the last minute; she would later be executed by the Bolsheviks in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia on May 16, 1920.

The anti-Bolshevik Whites committed very similar atrocities in areas they controlled. Forcing prisoners to disrobe before they were shot seems to have been a favored tactic to humiliate and dehumanize them on both sides, although the executioners may also simply have wanted warm coats and boots for themselves. Eduard Dune, a Latvian volunteer in the Red Guard, remembered coming across a mass grave where White partisans had murdered scores of prisoners:

"They pointed to a little hillock in the distance, saying that it was the mass grave of our men. None of the wounded had been taken prisoner; there were only dead men … Somehow I couldn’t believe a man could kill an unarmed prisoner, still less one who was wounded … On one occasion the special train did stop between two stations after we noticed three corpses tied to a pillar with telephone wire. Their bodies were covered with blood, and they were dressed in their underpants and sailors’ striped undershirts."

See the previous installment or all entries, or read an overview of the war.