Before these stories ended up on your kid's shelf, they were told to children tucked in bed.

1. Mrs. Piggle Wiggle by Betty MacDonald

Before she tried her hand at children’s books, Betty MacDonald already had a non-fiction book under her belt: The Egg and I, a memoir about her life as the wife of a chicken farmer in Washington state. After its success, she decided to put pen to paper to record some of the bedtime stories she used to tell her two daughters. The result was the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle series.

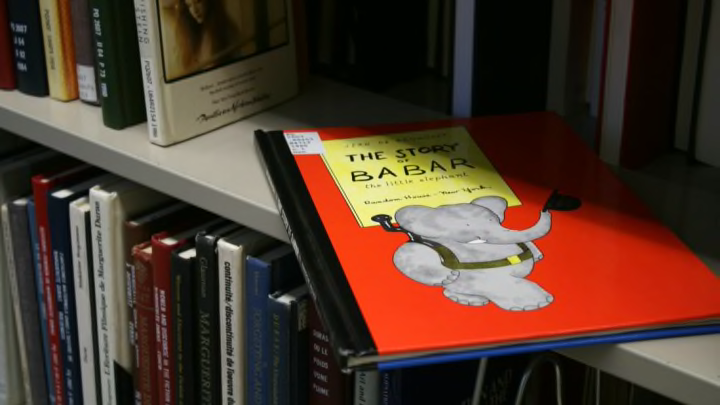

2. Babar by Jean de Brunhoff

In 1930, Mathieu de Brunhoff told his mother he wasn’t feeling well. To help him feel better, Cecile de Brunhoff whipped up a story about an orphaned elephant visiting Paris. Excited about the tale, the boys repeated it to their book illustrator father the next day, who thought the story had legs as a children’s book. Although it was slated to be published in 1931 with a byline for both Jean and Cecile, Cecile declined to take any credit, saying her role in creating the classic character was negligible.

3. Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne

Christopher Robin isn’t just the fictional guardian of the famous honey-loving bear. The Winnie-the-Pooh series was unofficially created bedtime stories Christopher Robin Milne’s father based on some of his son’s toys—a chubby bear, a donkey, a tiger, a kangaroo, and a piglet.

4. The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

According to the Tolkien Society, the author began writing down a bedtime story for his children—which would become The Hobbit—on the blank page of an exam. After it was completed, the publisher asked for a sequel, which inspired Tolkien to spend more than a decade writing The Lord of the Rings.

5. Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief by Rick Riordan

Riordan, already a successful author, created his Percy Jackson character when his son asked for some bedtime stories about Greek mythology. After he ran through all of the standard gods and heroes, Riordan invented Jackson. Because his son had recently been diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia, the author gave these traits to his hero as well.

6. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car by Ian Fleming

In the early 1960s, James Bond author Ian Fleming was recovering from a heart attack. During this down time, he decided to write down a story about a flying car that he had been telling his son, Caspar. Sadly, Fleming never saw the story turn into the huge hit it eventually became not only in bookstores, but also on stage and screen. The author died of a second heart attack in 1964, on Caspar’s birthday. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Magical Car came out just a few months later.

7. Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

Grahame began The Wind in the Willows as a bedtime story for his young son, Alastair, which he later continued over a series of letters while Alastair was away at boarding school. But this may not be as charming as it sounds—some historians suggest that Grahame hid behind the stories in order to avoid dealing with his son’s emotional issues. After Alastair begged his parents to allow him to visit for his birthday, Kenneth wrote, “I wish we could have all been together, but we shall meet again soon and then we shall have treats. Have you heard about the Toad? He was never taken prisoner by brigands at all. It was all a low trick of his ...” Alastair died by suicide in 1920.

8. Pippi Longstocking by Astrid Lindgren

Pippi Longstocking and her famous plaits were born when Astrid Lindgren’s daughter Karin was bedridden due to an illness. “Tell me a story about Pippi Longstocking,” Karin told her mother, pulling a funny name out of thin air. “Since the name was remarkable, it had to be a remarkable girl,” Lindgren later said. Her own bed rest due to a sprained ankle inspired Lindgren write the story down in 1944, and Pippi was published in 1945.

9. Thomas the Tank Engine by Wilbert Awdry

As a boy, Wilbert Awdry sat in bed, listening to steam engines “talking” to each other on the nearby Great Western Railway. Wilbert grew up, got married, and had a son. In 1943, when Christopher Awdry was stuck in bed with the measles, Wilbert remembered the trains from his childhood and created stories about talking trains named Edward, Gordon, and Henry. The stories got more and more detailed, later expanding to include a train named Thomas that young Christopher had gotten for Christmas. Thomas the Tank Engine was published in 1945.

10. The BFG by Roald Dahl

Not only did Roald Dahl tell two of his daughters a bedtime story featuring his famous BFG, he also acted the part. After telling them stories of the big, friendly giant who blew happy dreams into bedroom windows, Dahl would climb a ladder outside of their bedroom and use a bamboo cane to “blow” dreams through the window himself. The girls were too old to believe that the giant from the stories was real, but neither of them wanted to tell their father that. “He seemed to me, even then, to have a vulnerable core. So I said nothing,” his daughter Ophelia once said.

11. Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling

Kipling’s famous series of stories, including “How the Whale Got His Throat” and “How the Camel Got His Hump,” originally began as bedtime stories to Kipling’s daughter. He called them the “Just-So Stories” because his daughter required the stories to be repeated using exactly the same words and rhythm every night—“just so.”

12. The Iron Man: A Children’s Story in Five Nights by Ted Hughes

Hughes said he “just wrote … out” The Iron Man as he told the bedtime stories to his children over the course of a few nights. It was published in 1968 and later adapted into the animated movie The Iron Giant.

13. The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter

In 1893, Beatrix Potter wrote a story for Noel Moore, the young son of her former governess. Moore was bedridden with an illness, and Potter thought the illustrations and accompanying story would help cheer him up.

A version of this story ran in 2013; it has been updated for 2021.