The glass display cases called "curio cabinets" got both their form and their name from the historic "Cabinets of Curiosity." Though ubiquitous today, curio cabinets come from a rich history of passionate collectors and exultant status-seekers, looking for the flashiest proclamations of their presence in society.

Cabinets of Curiosity were also known as Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, or Wonder-Rooms. They first became popular during the Northern Renaissance, but that popularity didn't reach its apex until the Victorian era. Where amateur and professional scientists once kept their most prized specimens hidden away, society-folk now possessed the flashiest and rarest finds, and proudly displayed them for all to see. Though the traditional Wonder-Rooms—where entire rooms were filled with glass cases and collections—still existed in Victorian times, they were mostly the realm of royalty and academic institutions. The tradition of a personal collection to show off reached the newly burgeoning middle class, and the singular glass "curio cabinet" with one's most prized collection items skyrocketed in popularity.

Among those collections, there are many fascinating and unexpected finds. Here are a few collectors and their curious collections.

1. Beatrix Potter

Lactarius blennius, Beech Milkcap

Best known for her self-illustrated children’s stories, such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, Beatrix Potter was also an accomplished amateur mycologist, or one who studies fungus. She collected many volumes of illustrations and observations on lichens and mushrooms, and collected many dried specimens. In addition to mycology, she was also taken by the world of entomology—the study of insects—and botany, and acquired many insect and plant specimens, though she did not often keep them in her personal collection for long; many of the biological specimens given to her were passed along to London’s Natural History Museum. However, several cabinets of fossils and archaeological artifacts were kept in her possession and displayed proudly, even when she moved to the countryside to raise her award-winning sheep herd.

In addition to the Natural History Museum and National Art Library, a few of Potter’s archeological specimens, many of her original illustrations and paintings, and first-edition copies of all of her publications are found at the Armitt Collection in Ambleside, of which she was a member from its founding in 1912.

2. Franklin Delano Roosevelt

President Roosevelt was a philatelist—that is, he collected stamps. Beginning in childhood, FDR loved stamps, and had amassed a huge collection by the time he came to office. When asked how he remained calm and collected in such troubled times as the Great Depression, Roosevelt said, “I owe my life to my hobbies—especially stamp collecting.” In fact, the president loved stamps to the point where the Postmaster General had to get his approval on every new design while he was in office. Roosevelt even had a hand in designing many of the stamps issued during his term, and was known to sit down with the Postmaster General to collaborate on new stamp concepts, especially during his worst times in office. His passion for stamps (and his ability to indulge in them to a degree very few other philatelists got to) is what kept him “level-headed and sane” during the most stressful periods, according to his son.

Though he was most well-known for his stamp collecting, and influenced the field of philately more than any other group collectors, Roosevelt also had large collections of ship models and naval art, coins, and Hudson River Valley art. While some of his stamp collection has been dispersed to private collectors and museums across the country, the majority of his other collections are now found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

3. Sowerby Family

Wikimedia Commons

With four generations of conchologists (those who study shells), the Sowerby family amassed an incredible collection of shells and mollusc specimens. Confusingly for taxonomy historians and antiquarians, the son, grandson, and great-grandson of the naturalist patriarch (James de Carle Sowerby) had exactly the same name: George Brettingham Sowerby. They were almost always noted only as “G.B. Sowerby” in mollusca monographs and scientific papers, and even when the date of publication was known for the paper, the generations overlapped in their work. At least two of the three G.B. Sowerbys also illustrated both conchological and other zoological collections from various expeditionary voyages.

While initially known for their illustrations of the collection of the Earl of Tankerville during the 1810s, the Sowerbys later amassed a large collection of their own shells, and illustrated many times the number of specimens they personally owned. Unfortunately, the location of many of the Sowerby shells is unknown. However, their more than 4000 mollusca illustrations live on—as do many of the names given to the new species first detailed by the Sowerby family.

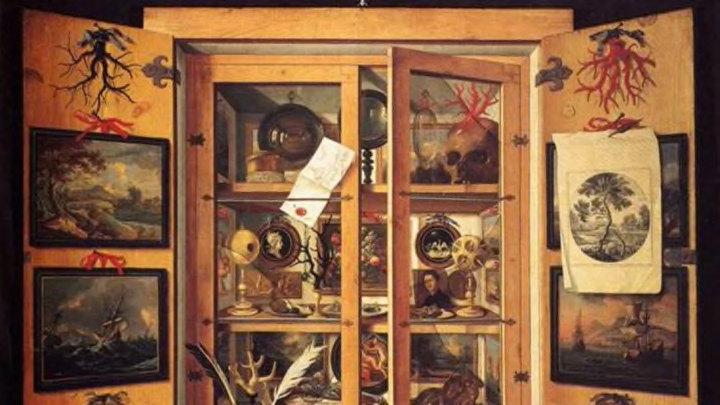

4. Ole Worm

Wikimedia Commons

One of the most notable “cabinets of curiosity” belonged to 17th century naturalist, antiquarian, and physician Ole Worm. A rich man by inheritance, Ole Worm collected specimens from the natural world, human skeletons, ancient runic texts, and artifacts from the New World. As an adult, Worm was the personal physician to King Christian IV of Denmark, but continued to collect and write about everything he found interesting.

Worm’s thoughts on various objects in his collection were at once rational and pre-modern. While he scoffed at those who passed off narwhal tusks as “unicorn horns”—and would set other naturalists straight when they asserted they had such a horn—he conjectured that perhaps the traits attributed to the mythological unicorn horn (such as being a universal antidote) still held true to the tusk. He used his collection to teach others, and his specimens and illustrations showed that two myths of the era were demonstrably false: lemmings did not appear from thin air, but reproduced like normal animals, and the bird of paradise did, indeed, have feet.

Outside of his Cabinet, Ole Worm owned a now-extinct Great Auk, kept for several years (until its death, and subsequent inclusion in the Cabinet) as a pet. An illustration of this bird while it was still alive is the only known representation of the species from life; all other representations have been created from dead specimens or were drawn from accounts made by sailors who had encountered the live animals.

5. Tradescant family

Another family with all-too-similar names, the John Tradescants were at least referred to as “Tradescant the Elder” and “Tradescant the Younger” in contemporary texts. During the course of the 17th century, the Tradescants amassed a huge collection from the natural world, as well as the world of anthropology. As the younger John travelled west, to Virginia, and collected objects and specimens in that direction, the elder travelled east, to Russia, and expanded the collection in that direction, too. Both Tradescants gathered objects from nature, weapons, armor, traditional garments, jewels, royal artifacts, and any other objects that caught their fancy. Eventually, the collection was arranged in such a way to form the first truly public museum—the Tradescant Ark. Unlike other cabinets of curiosity, anyone could tour it, not just aristocracy or friends of the family. All were welcome, assuming you could afford the 6p entry fee!

Though the elder John amassed a small fortune as a master gardener for royalty across Europe, the collection also included many priceless objects donated by society elites. After John the Younger’s death in 1662, Elias Ashmole published a catalogue of the objects in the museum, but had the book written in a format that appealed to popular culture, not just academics. Ashmole eventually took over the collection, and it formed the basis of the eponymous Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology at Oxford University. Though the museum no longer bears their name, the Tradescants are still honored in the name of the Tradescantia genus of flowering spiderworts.

6. Lady Charlotte Guest

Despite being brought up in a family that discouraged education for girls, Lady Charlotte Guest found her own way to learn a half-dozen languages, and knew the mythology and history of cultures around the world, by the time she married at 21. Her passion for learning and languages meant that she would eventually become best known for translating English books to Welsh, and publishing a collection of traditional Welsh folk tales in English, entitled Mabinogion.

However, her pursuits spanned far beyond the world of language. Her love of history and her upper-class upbringing stirred a fascination with ceramics and china from a young age. After being widowed at age 40, she found that one of her sons’ tutors, Charles Schreiber, had a similar passion, and soon re-married. She and her second husband travelled far and wide within Europe to collect some of the oldest and rarest ceramics and chinaware. Their huge collection was considered an honor to be shown while Schreiber lived, as he was a notable Dorset elite, and MP for Poole.

After his death in 1884, Lady Guest made the collection public, viewable for free. When she, too, passed away, she bequeathed the ceramics and china to the Victoria and Albert Museum. During her lifetime, she also amassed a large collection of board games, cards, and fans in her travels, which she donated to the British Museum.

7. Johann Hermann

Wikimedia Commons

Just like many university students, Johann Hermann started on one path, but ended up going somewhere completely different. Though initially studying philosophy, mathematics, and literature, Hermann eventually turned toward botany and medicine, receiving his M.D. in 1762 from the University of Strasbourg. Despite being a physician—and soon a Professor of Medicine at Strasbourg—he never stopped collecting specimens for his personal natural history cabinet, or cataloging the natural history around his region. He was soon made curator of the Botanical Gardens at the University of Strasbourg, and would head weekly natural history excursions into Alsace and Vosges.

During the French Revolution, Hermann was transferred to the School of Medicine at Strasbourg, and despite attempted suppression by the revolutionaries, he continued to maintain his collection, take students on cataloging excursions, and tend to the gardens at the University. Due to losing public and school funding for these projects, he put all of his own energy and wealth into them. Hermann even saved the statues of the Strasbourg Cathedral (due to be demolished by the Revolution, as they were “frivolous”) by burying them within the gardens.

After his death in 1800, Johann Hermann’s 18,000 natural history volumes formed the basis of the Natural History Museum of Strasbourg. His zoological and botanical collections formed the basis of the Zoological Museum of Strasbourg, and the gardens at the University of Strasbourg are still open to the public.

8. Robert Edmond Grant

Another physician who preferred the natural history world over medicine, Robert Edmond Grant collected one of the largest Cabinets of invertebrates in England during the first half of his life.

The Edinburgh-born Grant was a student of Erasmus Darwin’s writings—though the two never met—and learned the importance of dissection from none other than Georges Cuvier and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in the late 1810s. He later used his practice in dissection to teach Charles Darwin how to dissect marine invertebrates under a microscope, in their natural habitat. Though the two later had a falling-out over research domains, Darwin continued to use the methods and habits that Grant had taught him, as he came to his eventual conclusions on evolution.

Grant taught comparative zoology at University College London between 1827 and his death in 1874, but during the second half of his life, the enrollment in his courses was too low to pay him a living wage. Rather than sell off his collection (which, despite personally collecting, he believed belonged to those who could learn from it), or take up practicing medicine in London, he chose to live in the slums.

Interestingly, Robert Edmond Grant would probably object to being included in this list of curious collections. He campaigned for the Zoological Society collections to be curated and run by professionals rather than by aristocratic amateurs, and for the British Museum to become a research institution rather than simply a place to admire and gawk at the unusual and bizarre.

9. Joseph Mayer

At the other end of the spectrum from Robert Edmund Grant was Joseph Mayer, a well-to-do goldsmith of 19th century Liverpool, and a proponent of amateur contribution and control of large collections of antiques and curiosities. He collected potteries and Greek coins as a youth and jeweler’s apprentice, but eventually sold off his Greek coins to the French government.

The rest of Mayer’s collection kept growing, encompassing cultural artifacts, Wedgewood pottery, historic ceramics, ancient enamels, and the collections of many older amateur antiquarians who lived in the Merseyside and Cheshire regions. His successful goldsmithing business and the sale of his Greek coin collection gave him the funds to begin some of the first serious excavations of Anglo-Saxon artifacts inside England—up until Mayer, there was very little interest in that field, with antiquarians looking to Continental Europe and Egypt. Not that he didn’t love Egypt; one of the first truly Ancient Egyptian collections was held by Mayer for a time.

Despite the massive number of Egyptian acquisitions, Joseph Mayer’s passion was in England, and he’s been most known for his contributions to the field of Anglo-Saxon archaeology, and his contributions to the communities he lived in. Despite being an amateur collector and not thinking that he should leave the scholarly work and curation of artifacts to universities and researchers, Mayer and Robert Edmond Grant would have shared at least one conviction—that everyone is served when all levels of society are given access to lectures about the massive eclectic collections living right next door. Both the Mayer Trust (Joseph Mayer’s legacy) and the Grant Museum of Zoology (Grant’s legacy) give public lectures and provide for the public education to this day.

10. Ida Laura Pfieffer

Wikimedia Commons

One might assume that if you’re sailing at sea for over 100,000 km, travelling overland for 30,000 km, and spending your entire life after your sons have grown as a nearly nomadic explorer, there’s not much point in collecting things—after all, where would you keep them? Austrian lady Ida Laura Pfieffer saw things differently, though, and while making her record-setting and ground-breaking voyages and treks between 1842 and 1858, she collected and carefully documented thousands of plant, insect, marine, and mineral specimens, which currently reside in the Natural History Museums of Berlin and Vienna. Her 1856 collection of Malagasy (Madagascar) plants and insects was one of the first substantial looks at how unique the island was on a floral and entomological level, and many of her specimens were brand new species, even though she didn’t know it at the time.

On top of her biological specimens, Mrs. Pfieffer also collected an invaluable account of many of the world’s cultures, from the unique perspective of a female travelling solo, in a time when that was nearly unheard of for proper women. Despite her modesty, the fact that she was a mother of grown sons, and a widower (not simply a single lady riding the waves—far more taboo), her travels and travelogues were initially questioned and looked down upon as “lesser.” By the end of her life, though, she was highly respected and sought after by many notable exploration and geographical societies. Because of her gender, she had gained access to many places and cultures that shunned and attacked men, and gave a new perspective to many cultures that had been previously documented only by male explorers.

11. Athanasius Kircher

Wikimedia Commons

It takes quite a person to have a mineral named after them more than 300 years after their death, but in August 2012, kircherite gave Athanasius Kircher just such a distinction. Not that he was without distinction in his own time—he was a distinguished Jesuit polymath, wrote dozens of books on his observations of the natural and historical world, and had a massive and well-known Cabinet of Curiosities in Rome. Though he was not much of an inventor himself, he investigated everything he could, and his publications on many inventions (such as the “magic lantern”) gave much wider circulation and publicity to otherwise-unknown innovation.

Kircher was one of the first to take a scholarly interest in decoding Egyptian hieroglyphs, and he collected Egyptian statuary and artifacts in addition to manuscripts and transcriptions of carved hieroglyphic writing. Chinese artifacts, samples of minerals from his varied travels throughout Europe (including rocks taken while dangling from a rope inside the cone of Vesuvius), odd devices, and rare European antiquities rounded out the Museum Kircherianum—which Kircher founded in the 1670s—when his private residence was no longer large enough to house his entire collection. This museum was technically open to the public, but for most of its existence Athanasius found great pleasure in demanding scholarly letters of “recommendation” from nobility and clergy who would come through town and think to stop by. Even the pope wasn’t exempt from this requirement!

A notable exemption from Kircher’s Museum was one of the things he’s most known for: the “Katzenklaver,” or “cat piano.” While he illustrated the concept, it was in a work on how musical theories were universal in birdsong, instrumental pieces, and nature—thankfully for the cats, there’s zero evidence of him having created the “instrument,” or even having wanted to.

While Kircher himself was much more well-known than the Tradescant family thanks to his publications, his museum was less visited, especially after the Jesuits who owned the building it was housed in decided to move the curiosities to a less busy part of town. The plague ravaging Europe and Rene Descartes causing his personal popularity to dwindle probably didn’t help business, either. Despite the frustration with his treasures being moved towards the end of his life, Kircher continued to amass more objects and correspond with many academics and religious scholars until his death in 1680. It would take until nearly the 1700s before all of his artifacts (or at least the ones that were not sold off) were catalogued, and researchers are still coming across correspondences of his that had either been forgotten or never recorded in the first place.