Niccolò Machiavelli is arguably the most influential political thinker from the Italian Renaissance. Following the publication of his political theory masterwork The Prince in 1532, his name became synonymous with ruthless political machinations. But was this Florentine philosopher really that bad?

1. Niccolò Machiavelli had a front-row seat to Renaissance power struggles.

Machiavelli was born in 1469 in the independent Republic of Florence. Long before he became known as the first modern political theorist (not to mention an inspiration for House of Cards), Machiavelli worked as a diplomat in the service of the Florentine government. In 1498, at only 29 years old, he was appointed as the head of the Second Chancery, which put him in control of the city's foreign relations. His number-one concern was the potential return of the Medici family—the most infamous power brokers in Renaissance Italy—who had been ousted from Florence in 1494. Machiavelli oversaw the recruitment and training of an official militia to keep them at bay, but his army was no match for the Medici, who were supported by Rome's papal militia. When the Medici retook Florence in 1512, their first order of business was to fire—and, just for the heck of it, torture—Machiavelli.

2. Niccolò Machiavelli wrote The Prince to regain his lost status.

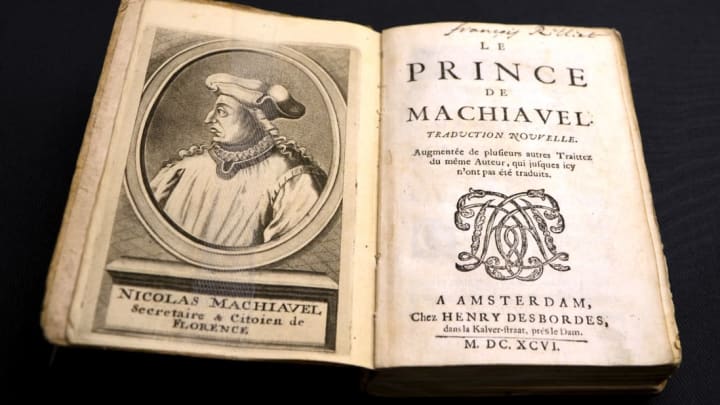

As a diplomat and a scholar in an age of constant warfare, Machiavelli observed and absorbed the rules of the political game. After he lost his job as a diplomat (and even served a short time in jail), he turned to scholarship, poring over the Latin texts of ancient Roman political philosophers for inspiration. By the end of 1513, he had completed the first version of what would become his masterwork: The Prince, a handbook for the power-hungry. The book offered tips to rising politicians for seizing power, and advice to incumbent princes for keeping it.

Ironically, Machiavelli dedicated the book to the Medici, hoping it would bring him back into their good graces. It remains unclear whether it was ever read by its intended audience, and Machiavelli never got to see The Prince go viral. It was published in 1532, five years after its author's death.

3. Niccolò Machiavelli compared the need for love to the value of fear.

One of The Prince’s primary lessons was that leaders must always try to strike a balance between seeking the love of their subordinates and inspiring fear. If a leader is too soft or kind, the people may become unruly; too cruel, and they might rebel. Machiavelli had a clear preference. "Since love and fear can hardly exist together,” he wrote, “if we must choose between them, it is far safer to be feared than loved."

4. The Prince’s ruthlessness made it notorious.

Machiavelli’s political thesis became notorious because it focused almost entirely on helping rulers get what they want at whatever cost—in other words, the end always justified the means. Other political thinkers, while acknowledging Machiavelli’s brilliance, were appalled by his mercenary take on statesmanship. In the 18th century, French essayist Denis Diderot described Machiavelli's work as "abhorrent" and summed up The Prince as "the art of tyranny." Friedrich Schiller, a proponent of liberal democracy, referred to The Prince as an unwitting satire of the kind of monarchical rule it supposedly espouses (“a terrible satire against princes”). David Hume, the Scottish polymath and inveterate skeptic, called Machiavelli "a great genius" whose reasoning is "extremely defective.” Wrote Hume, "There scarcely is any maxim in his Prince which subsequent experience has not entirely refuted.”

But 20th-century British philosopher Bertrand Russell disagreed, saying that Niccolò Machiavelli was merely being honest on a subject that most preferred with a good sugarcoating. “Much of the conventional obloquy that attaches itself to his name, is due to the indignation of hypocrites,” Russell wrote [PDF], “who hate the frank avowal of evil-doing.”

5. Shakespeare called villains Machiavels.

Machiavelli’s notoriety spread so quickly that by the 16th century his name had found its way into the English language as an epithet for crookedness. In Elizabethan theatre, it came to denote a dramatic type: An incorrigible schemer driven by greed and unbridled ambition. In the prologue for The Jew of Malta, playwright Christopher Marlowe introduces his villain as “a sound Machiavill.” Even William Shakespeare used the term as a derogatory shorthand. “Am I politic? Am I subtle? Am I a Machiavel?” one character in The Merry Wives of Windsor asks rhetorically, before adding an indignant, “No!”

6. The Prince was banned by the pope.

When Machiavelli was out of a job, he did what most Renaissance thinkers did: He found a patron. Pope Clement VII, a Medici who had been elected in 1523, was happy to support the scholar. The pope even commissioned one of Machiavelli’s longest works, the Florentine Histories, which Machiavelli presented in 1526. But after the posthumous publication of The Prince in 1532, the papacy’s attitude toward Machiavelli’s work chilled. When Pope Paul IV established Rome's first Index of Forbidden Books in 1557, he made sure to include The Prince for its promulgation of dishonesty and dirty politics. (Machiavelli’s passion for classical writers and their pagan culture didn’t appeal to Pope Paul, either [PDF].)

7. Niccolò Machiavelli collaborated with Leonardo da Vinci.

In 1503, when Machiavelli was struggling to fortify Florence against its enemies, he turned to the ultimate Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci.

According to a 1939 biography of Leonardo, the two "seem to have become intimate" when they met in Florence. Machiavelli used his power to procure commissions for Leonardo and even appointed him Florence's military engineer between 1502 and 1503. Machiavelli was hoping to harness Leonardo’s ingenuity to capture Pisa, a fledgling city-state which Florentine leaders had been eager to subdue for decades. As expected, Leonardo came up with a revolutionary plan. He contrived a system of dams that would block off one of Pisa’s main waterways, which could have brought Pisa to the brink of a drought and given Machiavelli all the leverage he could have asked for. But the plan failed. The dam system ended up interrupting Florence's own agriculture, and so the government terminated the project. Leonardo left his post after only eight months.

Some scholars believe that the encounter with Leonardo left a deep mark on Machiavelli’s political thinking. They point to Machiavelli’s repeated emphasis on the power of technological innovation to decide a war, a view which they believe Leonardo had inspired. Machiavelli’s writing is rife with idiosyncratic expressions that seem to have almost been lifted from Leonardo's notebooks.

8. Niccolò Machiavelli actually believed in a just government.

Scholar Erica Benner argues that, despite his reputation, Machiavelli wasn’t amoral. Although The Prince openly encouraged politicians to take and offer bribes, cheat, threaten, and even kill if necessary, Machiavelli knew that even rulers had to obey some sense of justice, Benner wrote in The Guardian. He recognized that the race for power comes with very few scruples, but he also recognized that without respect for justice, society falls into chaos.

This article was originally published in 2018.