Leonardo da Vinci was indisputably a genius, but his singular artistic vision may have been the result of seeing the world differently in more ways than one. A new paper argues that he had strabismus, a vision disorder where the eyes are misaligned and don’t look toward the same place at the same time. This disorder, visual neuroscientist Christopher Tyler argues, may have helped the artist render three-dimensional images on flat canvas with an extra level of skill.

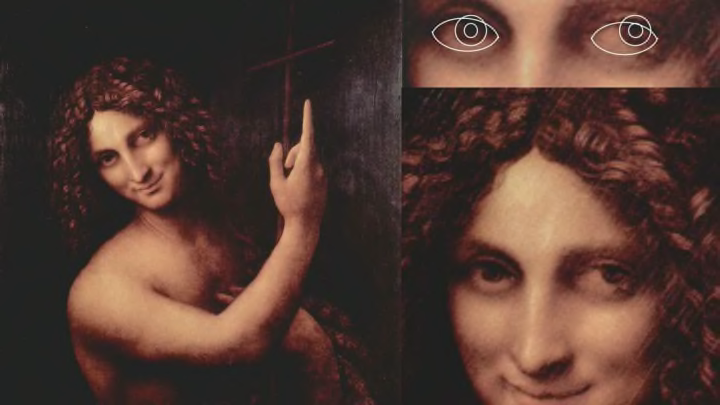

Tyler is a professor at City, University of London who has written a number of studies on optics and art. In this study, published in JAMA Ophthalmology, he examined six different artworks from the period when Leonardo was working, including Young John the Baptist, Vitruvian Man, and a self-portrait by the artist. He also analyzed pieces by other artists that are thought to have used Leonardo as a model, like Andrea del Verrocchio’s Young Warrior sculpture. Leonardo served as the lead assistant in the latter artist’s studio, and likely served as the model for several of his works. Leonardo was also a friend of Benedetto da Maiano, and possibly served as a model for his 1480 sculpture of John the Baptist. Tyler also looked at the recently auctioned Salvator Mundi, a painting that not all experts believe can be attributed to Leonardo. (However, at least one scientific team that examined the painting says it’s legit.)

With strabismus, a person’s eyes appear to point in different directions. Based on the eyes in Leonardo’s own portraits of himself and other artworks modeled after him, it seems likely that he had intermittent strabismus. When he relaxed his eyes, one of his eyes drifted outward, though he was likely able to align his eyes when he focused. The gaze in the portraits and sculptures seems to be misaligned, with the left eye consistently drifting outward at around the same angle.

“The weight of converging evidence suggests that [Leonardo] had intermittent exotropia—where an eye turns outwards—with a resulting ability to switch to monocular vision, using just one eye,” Tyler explained in a press release. “The condition is rather convenient for a painter, since viewing the world with one eye allows direct comparison with the flat image being drawn or painted.” This would have given him an assist in depicting depth accurately.

Leonardo isn’t the first famous artist whose vision researchers have wondered about. Some have speculated that Degas’s increasingly coarse pastel work in his later years may have been attributed to his degenerating eyes, as the rough edges would have appeared smoother to him because of his blurred vision. Others have suggested that Van Gogh’s “yellow period” and the vibrant colors of Starry Night may have been influenced by yellowing vision caused by his use of digitalis, a medicine he took for epilepsy.

We can never truly know whether a long-dead artist’s work was the result of visual issues or simply a unique artistic vision, but looking at their art through the lens of medicine provides a new way of understanding their process.