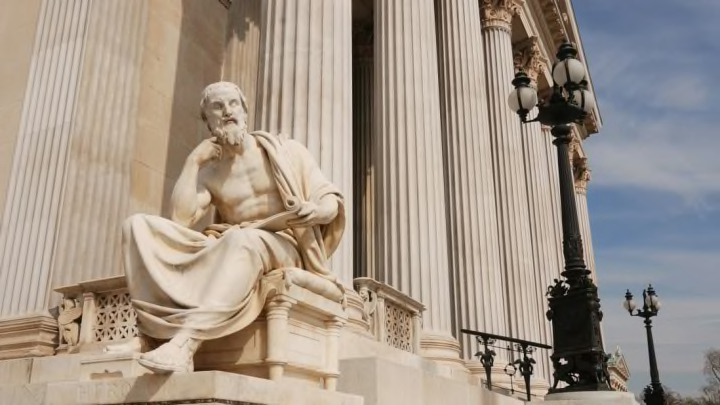

Widely considered one of the first serious works of history, Histories—written in the 5th century BCE by the Greek scholar Herodotus—is a highly influential account of the Greco-Persian wars, and offers one of the best glimpses into ancient cultures. Herodotus was remarkably scrupulous with his research, traveling across Europe and the Middle East to interview countless people. “[M]y rule in this history is that I record what is said by all as I have heard it,” he’d write.

Unfortunately, many of those people, it appears, lied to his face: Despite its merits, Histories is stuffed with whimsical inaccuracies. Consequently, some scholars have given Herodotus—dubbed the “Father of History”—a second sobriquet: “The Father of Lies.” As Tom Holland, a Herodotus translator, told The Telegraph: “The Histories are a great shaggy-dog story.” Here are some colorful passages (some of which may stretch the truth).

1. It was an honor to be eaten after your (sacrificial) death.

Herodotus had this to say of the Massagetae, a group who lived east of the Caspian Sea. “[W]hen a man is very old, all his relatives give a party and include him in a general sacrifice of cattle; then they boil the flesh and eat it. This they consider to be the best sort of death. Those who die of disease are not eaten but buried, and it is held a misfortune not to have lived long enough to be sacrificed.”

2. Egyptians loved cats so much they’d save them from a burning building.

Any devout cat-lover can imagine the following scene: “What happens when a house catches fire is most extraordinary: Nobody takes the least trouble to put it out, for it is only the cats that matter: every one stands in a row, a little distance from his neighbor, trying to protect the cats.”

3. In fact, they mourned their pet's death by shaving their eyebrows.

Perhaps the Egyptians loved their pets a little too much: “All the inmates of a house where a cat has died a natural death shave their eyebrows, and when a dog dies they shave the whole body including the head.”

4. In Babylon, women were auctioned into marriage based on looks.

“Once a year all the girls of marriageable age used to be collected together in one place, while the men stood round them in a circle; an auctioneer then called each one in turn to stand up and offered her for sale, beginning with the best-looking and going on to the second best as soon as the first had been sold for a good price.” (However, Herodotus noted that this practice was obsolete by his time; as with his other "facts," the veracity is debated.)

5. The desert was full of gigantic, terrifying ants.

Herodotus had this to say about India: “There is found in this desert a kind of ant of great size bigger than a fox, though not so big as a dog … These creatures as they burrow underground throw up the sand in heaps, just as our own ants throw up the earth, and they are very much like ours in shape.” (In 1996, a team of explorers theorized that Herodotus's ants, which were also said to dig up gold, were actually large marmots—which have been known to kick up gold dust in an area near the Indus River as they build their burrows.)

6. And hippos were basically a big, leathery horse.

Consider this description of a hippo, which Herodotus clearly never saw: “This animal has four legs, cloven hoofs like an ox, a snub nose, a horse’s mane and tail, conspicuous tusks, a voice like a horse’s neigh, and is about the size of a very large ox. Its hide is so thick and tough that when dried it can be made into spear-shafts.” (To say the least, Histories is not a very good biology resource.)

7. In Babylon, strangers were required to give you unsolicited medical advice.

Babylon sounds like an ill introvert’s nightmare: “They have no doctors, but bring their invalids out into the street, where anyone who comes along offers the sufferer advice on his complaint, either from personal experience or observation or similar complaint in others … Nobody is allowed to pass a sick person in silence; but one must ask him what is the matter.”

8. The Persians were extremely good at delivering mail.

“No mortal thing travels faster than these Persian couriers," Herodotus writes. "The whole idea is a Persian invention, and works like this: riders are stationed along the road, equal in number to the number of days the journey takes—a man and a horse for each day. Nothing stops these couriers from covering their allotted stage in the quickest possible time—neither snow, rain, heat, nor darkness.” (If that sounds familiar, it's because these lines inspired the USPS’s unofficial "neither snow nor rain ..." motto [PDF]).

9. Some women in Libya wore adornments indicating their number of sexual conquests.

Herodotus describes the Gindane people of Libya like this: “The women of this tribe wear leather bands round their ankles, which are supposed to indicate the number of their lovers: each woman puts on one band for every man she has gone to bed with, so that whoever has the greatest number enjoys the greatest reputation because she has been loved by the greatest number of men.” (Incidentally, Herodotus also believed the Gindanes lived among the mythical Lotus Eaters, who were famous for their apathy.)

10. In Bulgaria, death was a cause for celebration!

According to Herodotus, the Trausi, a tribe living in the Rhodope mountains of southeastern Europe, celebrated birth and death a little differently: “When a baby is born the family sits round and mourns at the thought of the sufferings the infant must endure now that it has entered the world, and goes through the whole catalogue of human sorrows; but when somebody dies, they bury him with merriment and rejoicing, and point out how happy he now is and how many miseries he has at last escaped.”

11. Ethiopia was full of hole-dwelling people who shrieked like bats.

The Garamantes were a tribe in Libya. According to “The Father of History,” they passed their time by hunting quick-footed trolls: “[They] hunt the Ethiopian hole-men, or troglodytes, in four-horse chariots, for these troglodytes are exceedingly swift of foot—more so than any people of whom we have information. They eat snakes and lizards and other reptiles and speak a language like no other, but squeak like bats.”

12. Egyptians overcame baldness with the power of the sun.

“I noticed that the skulls of the Persians are so thin that the merest touch with a pebble will pierce them, but those of the Egyptians, on the other hand, are so tough that it is hardly possible to break them with a blow from a stone. I was told, very credibly, that the reason was that the Egyptians shave their heads from childhood, so that the bone of the skull is hardened by the action of the sun—this is also why they hardly ever go bald, baldness being rare in Egypt than anywhere else.”

13. Sea nymphs could save the day! (Maybe.)

Even for Herodotus, some stories were just too crazy to accept—like this tale describing a naval fleet caught in a rough weather: “The storm lasted three days, after which the Magi brought it to an end by sacrificial offerings, and by putting spells on the wind, and by further offerings to Thetis and the sea-nymphs—or, of course, it may be that the wind just dropped naturally.”

There you have it: If you want to know where Herodotus draws the line, it’s weather-conjuring sea-nymphs.