In the 1910s, if you strolled through Prague in the evenings, you might have caught a glance of a half-naked (or fully nude) Franz Kafka shamelessly jumping, stretching, and spinning in front of his apartment window.

By his late twenties, Kafka was obsessed with bulking up. “My body is too long for its weakness,” he once wrote; “it hasn’t the least bit of fat to engender a blessed warmth, to preserve an inner fire, no fat on which the spirit could occasionally nourish itself beyond its daily need without damage to the whole.” The author's own doctors agreed with that sentiment. In 1907, a physician said Kafka's body was, “thin and delicate. He is relatively weak.” (To salt the wound further, the same doctor described Kafka’s clavicle as “drumstick-shaped.”)

That, however, started to change after Kafka discovered the work of Jørgen Peter Müller.

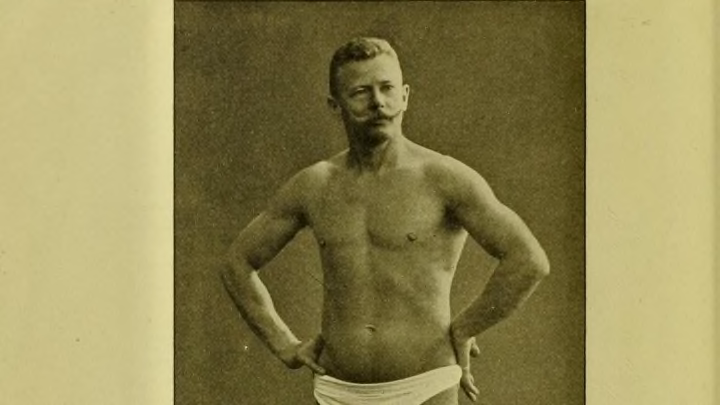

A Danish physical fitness guru known to go skiing in nothing but a loincloth, Müller was arguably then one of the most famous people in all of Europe. In 1904, he published a pamphlet called My System, which promised to transform any weakling’s body into that of a Greek god with just 15 minutes of daily exercise. His fitness books sold in the millions and were translated into at least 25 languages. Müller’s methods were so popular that his name became a verb—"to Müller” was the equivalent of “to exercise.”

As Sarah Wildman writes for Slate, My System is “something like a precursor to Pilates; it borrows from ballet, and it needs no equipment, other than commitment. It is strict but appealingly accessible.” The regimen consists of bodyweight exercises—toe touches, squats, leg raises, modified push-ups—that could be performed from the comfort of a bedroom. No dumbbells required.

The book appeared have been written just for Kafka, who was used to sedentary office drudgery—he had once worked 12 hours each day at an insurance office. “The town office type is often a sad phenomenon,” Müller intones, “prematurely bent, with shoulders and hips awry from his dislocating position on the office stool, pale, with pimply face.”

Seeing himself in Müller's writing, Kafka became something of an calisthenics zealot. Like a modern CrossFit fanatic, Kafka would sing the praises of the routine to everybody—even writing a letter to his fiancée insisting she try it. (It may not surprise you that they never married.) Twice a day, he’d shamelessly “Müller” in front of his window, sometimes completely nude.

To both Kafka's and Müller’s credit, the exercise book gets a lot of things right. It preaches the importance of core and back strength and offers solid exercises to accomplish those goals. Müller also gives health tips that weren't so common back in the day, advising people to drink alcohol in moderation, to hydrate properly, to clean their teeth, and to sleep for eight hours every night. As Wildman notes, “half of his exercises are now part of the standard back-pain recommendations for patients.”

Want to give Kafka’s workout routine a try? Check out Müller’s guide here at the Internet Archive. (Window shades optional, but strongly suggested.)