Chicago White Sox pitcher Ken Kravec was warming up on the mound when he noticed the rush of people on the field. Preparing for a second game in a doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers, the White Sox had lost the first by a score of 4-1. The crowd had been rowdy and insolent throughout, but this was something else.

As Kravec stood on the mound, thousands of attendees descended from the bleachers and slid down poles marking foul ball territory. They dug up dirt in the field and began running off with bases. A few tried removing home plate. Kravec soon joined his teammates in the dugout, where both the White Sox and the Tigers were staring in disbelief at the mayhem.

The source of their unrest was happening in center field. It was a bonfire made up of thousands of records, mostly disco, that the team had invited fans to bring with them for a reduced admission price. Management had expected perhaps 35,000 people. Nearly 50,000 showed up. On July 12, 1979, Disco Demolition Night would go down as one of the most infamous evenings in the history of Major League Baseball. It was not only the destruction that stirred controversy, but the concern that the demonstration had a far more disturbing subtext.

In the mid- to late-1970s, attendance at many major league baseball stadiums was down. Teams around the country tried a variety of stunts to stir interest, including Cleveland’s notorious 10-cent beer night in 1974 that sparked a mountain of misbehavior. The White Sox were in particularly dire need of something to reinvigorate their franchise. In 1979, an average of just 10,000 to 16,000 people were coming to their games, though Comiskey Park could seat 45,000.

Team owner Bill Veeck tried to turn the games into a spectacle. There was a scoreboard that could set off pyrotechnics and other attention-grabbing additions, but nothing seemed to stick. The action on field was equally tepid. Midway through the season, the Sox held a disappointing 35-45 record.

Veeck’s son, Mike Veeck, was assistant business manager for the team. Like many Chicago residents, he had heard local radio shock jock Steve Dahl on WLUP, an FM rock station serving the area. Dahl was prone to disparaging the then-popular genre of disco on air, playing records and then keying up an explosion sound effect. Dahl had lost his previous job on WDAI after it went all-disco, giving him an origin story of sorts for his contempt.

Dahl, of course, wasn’t entirely alone in his disco dismissal. A trendy and dance-friendly format, disco had been dominating airwaves and Billboard charts, with Donna Summer and the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack on heavy rotation and acts ranging from KISS to the Rolling Stones recording disco singles. Even 1977’s Star Wars scored a hit with a disco tie-in album. In the first half of 1979, 13 of the top 16 tracks were disco. Rock enthusiasts like Dahl thought the genre was inferior to their preferences and decried its widespread success.

Though Veeck had no particular opinion about disco, he saw an opportunity to partner with Dahl for a stunt. At Comiskey Park, attendees could get in for just 98 cents if they brought in one disco record for what was dubbed Disco Demolition Night. Once employees collected the records, Dahl would appear between the doubleheader with the Tigers and proceed to queue up an explosion.

Dahl agreed and promoted the appearance heavily on the air. The Veecks contacted Chicago police and asked for increased security as they expected up to triple their usual attendance as a result of the promotion—upwards of 35,000 people. With interest in the Sox low all season, it’s not clear that authorities took the request seriously.

They should have. Come July 12, people began lining up for the evening doubleheader as early as 4 p.m. A cursory glance at the crowd revealed that many of them were not baseball fans. There were a large number of teenagers as well as several attendees wearing concert T-shirts, a hint that the promotion had attracted people looking for a spectacle rather than a sporting event. Inside, many clung to their records instead of tossing them in the bins near the gates. As seats began filling up inside, thousands of people were armed with vinyl records. The scene had the makings of an active demonstration, not a passive entertainment.

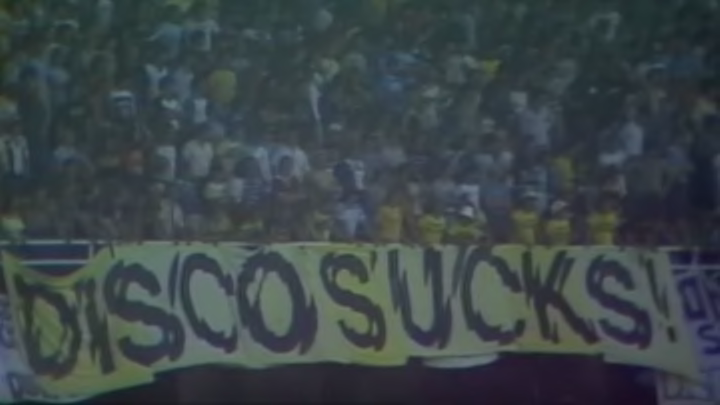

As the White Sox and Tigers played their first game, spectators began tossing drinks and records onto the field. Chants of “disco sucks” filled the stadium. Firecrackers snapped in the air. When the game wrapped, Dahl emerged on the field in military fatigues, while a pile of disco records sat in center field. Inciting the crowd more, Dahl grabbed a microphone and let loose anti-disco invective before giving the signal to immolate the records. A fuse was lit and soon the pile was on fire.

Rather than pacify the crowd, the sight of the blaze seemed to embolden them. Kravec and the other players watched as people swarmed the field, sliding down poles and risking injury by jumping from the deck to the grass. Records were hurled, sticking into the ground. People tried to climb inside the skybox occupied by the wife and children of team manager Don Kessinger. Cherry bombs were ignited and exploded. The air took on a smoky atmosphere of flying projectiles, with an estimated 7000 people—almost the typical crowd of a regular season game—trampling the diamond.

Some players armed themselves with bats, their nearest available weapon. Announcer Harry Caray took to the public address system to call for order, which went ignored.

The crowd, however raucous, was largely nonviolent and no fights were reported. When police finally arrived 30 minutes later to restore order, 39 people were arrested for disorderly conduct. A vendor with a broken hip was the worst injury recorded. The main damage was to the field itself, which had been cratered by the explosion.

With no other alternative, the Sox were forced to forfeit the game, though the team wanted to call it a rain delay. The only rain had been from the beer bottles.

The official attendance was reported as 47,795, though Mike Veeck believed the crowd was as large as 60,000. Many had climbed over gates and overwhelmed ushers, crashing the stadium and getting in without paying admission. Disco Demolition Night had quickly turned from a purportedly clever marketing idea to a nightmare. Dahl would later admit to being more than a little scared by the whole ordeal.

The forfeit was the first by a major league team in five years. Soon, Bill Veeck would be out as president, selling the team in 1981; Mike Veeck didn’t get another job in baseball for 10 years—both situations reportedly due in large part to the near-riot that had transpired. But that would not be the only fallout from the stunt.

As ushers admitted fans into the stadium, they noticed a number of the records being turned in were by black artists—not just disco, but soul, R&B, and other genres. Steve Wonder and Marvin Gaye were among the performers destined for the bonfire. Because disco was popular among minority groups including Latinos and the gay community, observers believed Dahl had stirred up something more sinister than a simple distaste for disco music.

“People started running up on me, yelling ‘Disco sucks!’ in my face, getting in my face, confronting me as a person that ‘represents’ disco, and there were thousands of people running around in this stadium buck wild,” Vince Lawrence, an usher at the stadium that night, told Yahoo! Entertainment in 2019. “I started going, ‘Wait a minute, why am I disco?’” Lawrence, who is black, was actually wearing a shirt endorsing Dahl’s radio station.

Later, Lawrence said he was surprised most of the media coverage had been about the damage done to the baseball field, not the undercurrent of the protest. “It was evident that it was seen as OK, because the next day it was in the paper everywhere, all over the news, but the biggest complaint about the issue was not, ‘Hey, why the heck is it OK to just actively destroy somebody’s culture?’ That wasn’t the story. The story was like, ‘Hey, the lawn on this baseball field got f***ed up.'"

In interviews, Dahl refuted any claims he had intended to stir up any racial animosity. He simply hated disco and decided to engage in the kind of promotional stunt common among disc jockeys at the time. But the controversy returned in summer 2019, when the White Sox offered a T-shirt “commemorating” the demolition stunt. The move was criticized for being in poor taste.

As a tool to diminish disco, Dahl and Veeck’s themed evening was somewhat successful. Radio stations took to playing less of it and record labels began to shy away from the genre, forcing it underground. Of course, it’s likely disco would have been a cultural fad regardless. But what is superficially an outrageous story about a sporting stunt gone awry has also been looked at as a rejection of what disco represented: a diversity in tastes and spirit. It's for that reason Disco Demolition Night remains an infamous black eye in baseball history.