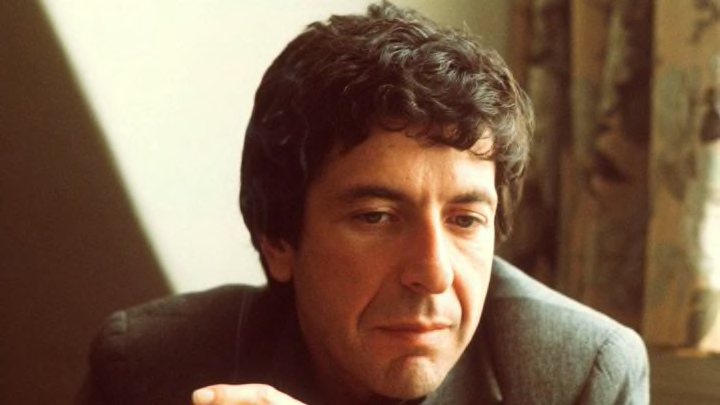

In the late 1970s, Leonard Cohen sat down to write a song about god, sex, love, and other mysteries of human existence that bring us to our knees for one reason or another. The legendary singer-songwriter, who was in his early forties at the time, knew how to write a hit: He had penned "Suzanne," "Bird on the Wire," "Lover, Lover, Lover," and dozens of other songs for both himself and other popular artists of the time. But from the very beginning, there was something different about what would become "Hallelujah"—a song that took five years and an estimated 80 drafts for Cohen to complete.

In the 35 years since it was originally released, "Hallelujah" has been covered by more than 300 other artists in virtually every genre. Willie Nelson, k.d. lang, Justin Timberlake, Bono, Brandi Carlile, Bon Jovi, Susan Boyle, Pentatonix, and Alexandra Burke—the 2008 winner of the UK version of The X Factor—are just a few of the individuals who have attempted to put their own stamp on the song. After Burke’s soulful version was downloaded 105,000 times in its first day, setting a new European record, “Hallelujah” soon became a staple of TV singing shows.

It's an impressive feat by any standard, but even more so when you consider that "Hallelujah"—one of the most critically acclaimed and frequently covered songs of the modern era—was originally stuck on side two of 1984’s Various Positions, an album that Cohen’s American record label deemed unfit for release.

“Leonard, we know you’re great,” Cohen recalled CBS Records boss Walter Yetnikoff telling him, “but we don’t know if you’re any good.”

Yetnikoff wasn’t totally off-base. With its synth-heavy ’80s production, Cohen’s version of “Hallelujah” doesn’t announce itself as the chill-inducing secular hymn it’s now understood to be. (Various Positions was finally released in America on the indie label Passport in 1985.) Part of why it took Cohen five years to write the song was that he couldn’t decide how much of the Old Testament stuff to include.

“It had references to the Bible in it, although these references became more and more remote as the song went from the beginning to the end,” Cohen said. “Finally I understood that it was not necessary to refer to the Bible anymore. And I rewrote this song; this is the ‘secular’ ‘Hallelujah.’”

The first two verses introduce King David—the skilled harp player and great uniter of Israel—and the Nazarite strongman Samson. In the scriptures, both David and Samson are adulterous poets whose ill-advised romances (with Bathsheba and Delilah, respectively) lead to some big problems.

In the third verse of his 1984 studio version, Cohen grapples with the question of spirituality. When he’s accused of taking the Lord’s name in vain, Cohen responds, hilariously, “What’s it to ya?” He insists there’s “a blaze of light in every word”—every perception of the divine, perhaps—and declares there to be no difference between “the holy or the broken Hallelujah.” Both have value.

“I wanted to push the Hallelujah deep into the secular world, into the ordinary world,” Cohen once said. “The Hallelujah, the David’s Hallelujah, was still a religious song. So I wanted to indicate that Hallelujah can come out of things that have nothing to do with religion.”

Amazingly, Cohen's original "Hallelujah" pales in comparison to Velvet Underground founder John Cale’s five-verse rendition for the 1991 Cohen tribute album I’m Your Fan. Cale had seen Cohen perform the song live, and when he asked the Canadian singer-songwriter to fax over the lyrics, he received 15 pages. “I went through and just picked out the cheeky verses,” Cale said.

Cale’s pared down piano-and-vocals arrangement inspired Jeff Buckley to record what is arguably the definitive “Hallelujah,” a haunting, seductive performance found on the late singer-songwriter’s one and only studio album, 1994’s Grace. Buckley’s death in 1997 only heightened the power of his recording, and within a few years, “Hallelujah” was everywhere. Cale’s version turned up in the 2001 animated film Shrek, and the soundtrack features an equally gorgeous version by Rufus Wainwright.

In 2009, after the song appeared in Zack Snyder's Watchmen, Cohen agreed with a critic who called for a moratorium on covers. “I think it’s a good song,” Cohen told The Guardian. “But too many people sing it.”

Except “Hallelujah” is a song that urges everyone to sing. That’s kind of the point. The title is from a compound Hebrew word comprising hallelu, to praise joyously, and yah, the name of god. As writer Alan Light explains in his 2013 book The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of "Hallelujah,” the word hallelujah was originally an imperative—a command to praise the Lord. In the Christian tradition, it’s less an imperative than an expression of joy: “Hallelujah!” Cohen seemingly plays on both meanings.

Cohen’s 1984 recording ends with a verse that begins, “I did my best / It wasn’t much.” It’s the humble shrug of a mortal man and the sly admission of an ambitious songwriter trying to capture the essence of humanity in a pop song. By the final lines, Cohen concedes “it all went wrong,” but promises to have nothing but gratitude and joy for everything he has experienced.

Putting aside all the biblical allusions and poetic language, “Hallelujah” is a pretty simple song about loving life despite—or because of—its harshness and disappointments. That message is even clearer in Cale’s five-verse rendition, the guidepost for all subsequent covers, which features the line, “Love is not a victory march.” Cale also adds in Cohen’s verse about sex, and how every breath can be a Hallelujah. Buckley, in particular, realized the carnal aspect of the song, calling his version “a Hallelujah to the orgasm.”

“Hallelujah” can be applied to virtually any situation. It’s great for weddings, funerals, TV talent shows, and cartoons about ogres. Although Cohen’s lyrics don’t exactly profess religious devotion, “Hallelujah” has become a popular Christmas song that’s sometimes rewritten with more pious lyrics. Agnostics and atheists can also find plenty to love about “Hallelujah.” It’s been covered more than 300 times because it’s a song for everyone.

When Cohen died on November 7, 2016, at the age of 82, renewed interest in “Hallelujah” vaulted Cohen's version of the song onto the Billboard Hot 100 for the first time. Despite its decades of pop culture ubiquity, it took more than 30 years and Cohen's passing for “Hallelujah”—the very essence of which is about finding beauty amid immense sadness and resolving to move forward—to officially become a hit song.

“There’s no solution to this mess,” Cohen once said, describing the human comedy at the heart of “Hallelujah. “The only moment that you can live here comfortably in these absolutely irreconcilable conflicts is in this moment when you embrace it all and you say 'Look, I don't understand a f***ing thing at all—Hallelujah! That's the only moment that we live here fully as human beings.”