The Great Canoe at New York City's American Museum of Natural History is one of the largest dugout canoes on Earth. Suspended from the ceiling of the Grand Gallery, it appeared weightless. Visitors entering from 77th Street may have assumed the canoe was built for the space, like the museum's massive blue whale model. But the real history of the vessel can be traced back 150 years to the Pacific Northwest. Now, as the artifact moves locations for the first time in 60 years, AMNH is working with First Nations advisors to strengthen the connections between the new exhibit and its past.

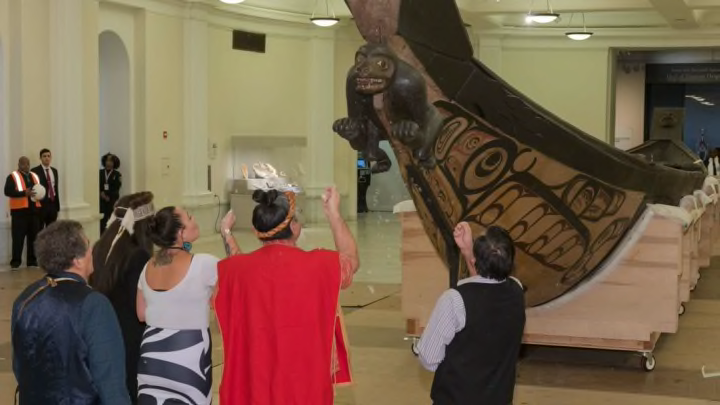

On January 28, 2020, the Great Canoe was rolled in a custom cradle from the Grand Gallery to the neighboring Northwest Coast Hall. Design elements of the Great Canoe indicate it came from the Heiltsuk and Haida nations on Canada's Pacific coast, but the identities of its builders and many other details of its construction remain a mystery. A group of representatives from First Nation communities in British Columbia kicked off the event with traditional song and prayer. They concluded the ceremony by circling the boat and blowing tufts of eagle down over it. The Indigenous representatives then explained the significance of canoes to all First Nations in the region.

"Canoes are absolutely central to the cultures of all the people who are represented here today," Nuu-chah-nulth artist and cultural historian Haa'yuups, or Ron Hamilton, who's co-curating the renovation of the Northwest Coast Hall, said. "All of our people made their livings not long ago in and out of the sea [...] From birth until death, our people lived in and out of canoes."

Even to cultures built around sea travel, the canoe at AMNH is exceptional. It measures 63 feet long and was dug out of a single Western red cedar tree. The body was carved in the 1870s, and it's possible that the orca and raven illustrations and the seawolf figurehead were added after its initial construction. AMNH trustee Heber Bishop acquired the piece for the museum in the late 19th century, and following a journey that included travel on a ship, train, and horse-drawn carriage, it arrived in New York in 1883. The Great Canoe was displayed in the Northwest Coast Hall from 1899 to 1960, when it was moved to the Grand Gallery where it resided most recently. January's move marks the boat's return to the hall after a six-decade absence.

The relocation is part of the museum's two-and-a-half-year revitalization of the Northwest Coast Hall. The exhibit includes hundreds of objects and nearly a dozen totem poles, all of which originate from the same general region of the world as the canoe. Like the canoe, the stories of many of these artifacts have been lost or misinterpreted over the years—largely because none of their original owners were involved in getting them onto the museum floor.

AMNH is determined not to repeat the mistakes of the past with this new project. By seeking the counsel of 10 First Nation advisors, each coming from a different nation represented in the hall, the museum hopes to reflect their cultures in a rich, accurate light. "[Collaboration] is something we definitely try to encourage, specifically in relation to conservation," museum curator of North American ethnology Peter Whitely tells Mental Floss. "We really want it to be a participatory collaboration, because long-term, it's our responsibility to these communities to continue a pattern of mutual engagement."

Jisang, or Nika Collison, of the Ts'aah clan of the Haida Nation, spoke of her role as advisor following the canoe move ceremony. The museum sends her digital images of the artifacts being restored—that way, when she's home, she can consult with other members of her community and dig up context for each piece. "We get these great big files with these digital photos so you can go home and work with the carvers or the weavers that know things," she said. One photo she received showed a wolf mask missing its ears: "My brother was going through it, and he said, 'I think I found the ears,' because they were labeled as a separate piece."

The Northwest Coast Hall is currently closed for the revitalization effort, and in 2021, it will reopen with the Great Canoe in its new position suspended from the ceiling. In the meantime, advisors will continue working with the museum to update the collection. "We’re putting our treasures back together," Collison said, "because that’s the history of museums, that a lot of things came in without our knowledge to go along with it."