Gary VandenBerg, the assistant manager of the Piggly Wiggly grocery store in Appleton, Wisconsin, was accustomed to fielding customer requests and making sure everyone left happy. But in December of 1973, VandenBerg was confronted with a peculiar situation.

His store was running out of toilet paper. Fast.

Customers plucked rolls from shelves as quickly as they could be stocked. A woman came in looking to purchase 10 cases. Store management decided to triple their normal order. It wasn’t enough. The Piggly Wiggly had been inexplicably besieged by people hoarding bathroom tissue.

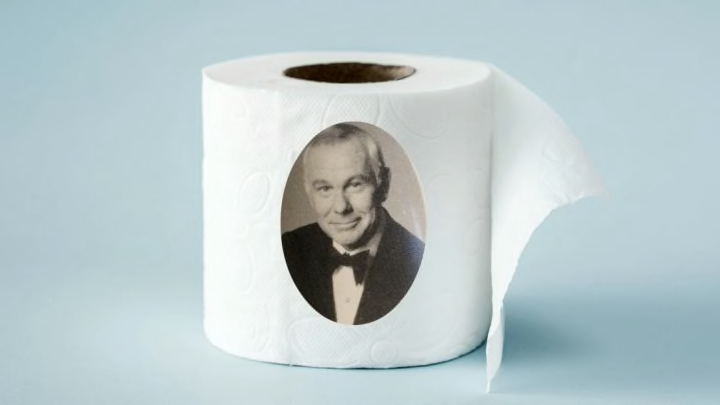

Just a few days later, this local epidemic would soon turn into a national concern. And Johnny Carson would be to blame.

In 1973, the United States was beginning to grow accustomed to shortages. Oil prices had soared due to an embargo; the stock market was plunging.

In the midst of this, Harold V. Froehlich—a Republican congressman from the heavily-forested eighth district of Wisconsin—began receiving complaints from constituents that pulp paper was getting harder to come by. Around the same time, Froehlich noticed some news reports of a tissue shortage in Japan. He investigated and believed the source of the claim was companies who were exporting more pulp paper out of the United States to avoid federal price tolls on domestic sales.

Believing this could lead to a serious paper shortage of all types, Froehlich issued a press release on November 16, 1973. Few news outlets paid much attention. Then Froehlich discovered the federal government’s National Buying Center had failed to secure their normal number of bids for a four-month toilet paper supply intended for soldiers and bureaucrats. Froehlich issued a second press release on December 11, this one focusing more on the potential for a shortage of not only paper, but the one consumer product that no American could live without: “The U.S. may face a serious shortage of toilet paper within a few months,” he wrote. “We hope we don’t have to ration toilet tissue … a toilet paper shortage is no laughing matter.”

Froehlich’s intention was to bring attention to what he perceived to be an industrial problem by pointing out a shortage that would affect every household in the country.

It worked. News media began to cover the story on television and in print. The more outlets that picked it up, the more words like “potentially” were lost in translation. Almost immediately, consumers were buying shopping carts full of TP out of fear they might soon not be able to buy any.

On December 19, roughly a week after Froehlich’s second and more dire warning, Tonight Show host Johnny Carson made mention of the story in his monologue. "Of all the shortages we have ... there's a gasoline shortage," he said. "You know what else is disappearing from the supermarket shelves? Toilet paper! Ah, ha, ha! You can laugh now! There is an acute shortage of toilet paper in the good old United States. We gotta quit writing on it. But I wanna tell ya, it is serious. I just saw a commercial ... where a Mrs. Olsen comes in with a shopping bag and a housewife says, 'Forget the coffee, just give me the shopping bag.'"

With an audience of roughly 20 million viewers, Carson’s mention activated a national paper panic. Millions of people cleaned retail shelves of rolls. A store in Seattle ordered 21 cases but received only three, adding to the hysteria. One woman reported asking for toilet paper rather than gifts for her party. Stores tried setting limits of two to four rolls per customer. Others raised prices from 39 to 69 cents per roll—not to gouge customers, but to dissuade them from buying too much. Other paper products like towels and cups were also in short supply. There were even rumors that a toilet paper black market had emerged, where hoarders were offering rolls at a mark-up.

“I’m used to being able to go when I want to, but suddenly I think I’m going to have to start curbing my habits,” one woman said.

The more toilet paper that was purchased, the more customers unable to find toilet paper were convinced there really was a shortage. Froehlich was right about the crisis—only he was the one who had unintentionally caused it.

The toilet paper frenzy continued into 1974—but eventually, consumers realized Froehlich’s concerns simply weren’t materializing. Respected CBS broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite urged calm on his newscast and aired footage from the Scott Paper Company that demonstrated toilet paper was coming off the factory line without delay. Even Froehlich walked back his comments, though his third press release didn’t get nearly the same attention as the one where he raised the potential for bathrooms devoid of toilet tissue.

When he returned from his holiday break, Carson felt compelled to issue an apology. “For all my life in entertainment, I don’t want to be remembered as the man who created a false toilet paper scare,” he told viewers. “I just picked up the item from the paper and enlarged it somewhat … there is no shortage.” The furor soon wound down.

Strangely, it would not be Carson’s only brush with bathroom controversy. In 1977, the host was able to win a lawsuit against Earl J. Braxton, a Michigan businessman who marketed portable toilets under a name that was familiar to Tonight Show viewers: Here’s Johnny.