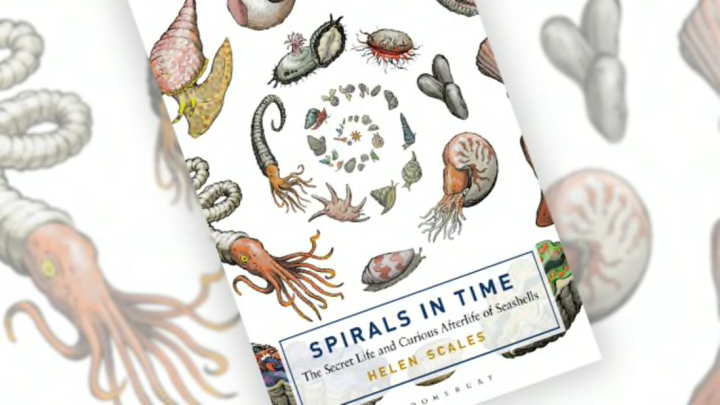

When wandering the beaches this summer, have more to say about the shells you find than why you can hear the ocean in them. Marine biologist Helen Scales’s Spirals in Time: The Secret Life and Curious Afterlife of Seashells is packed full of interesting facts about seashells and the creatures that create them. Here are just a few you can use to wow fellow sunbathers this summer.

1. MOLLUSKS MAKE ONLY ONE SHELL.

Mollusks use calcium carbonate and proteins, secreted from their mantles, to build their shells. As a mollusk grows, so does its exoskeleton. “They are among the few animals on the planet that wander around carrying with them the same body armor they had as babies; the pointy tip or innermost whorl is the mollusk’s juvenile shell,” Scales writes. “Day by day, the mollusk shell slowly expands, making room for the soft animal growing inside.”

2. MOST SHELLS OPEN TO THE RIGHT.

Although there are some species with shells that are always sinistral, or left opening, nine out of 10 shells are dextral, meaning they open to the right. Because of their rarity, “shell collectors go crazy” for sinistral specimens, Scales says, “so much so that over the years clandestine trades have prospered in fake lefties.”

Though shell collectors might love them, there are dire consequences to being a sinistral animal: Mating with dextral mollusks is pretty much impossible. To see what happens when lefties and righties tried to mate, researchers placed pairs of left- and right-opening Roman snails in tanks. “No matter how much the left-right partners are feeling in the mood,” Scales writes, “the slurp of a baby snail’s feet never issues from mating cubicles.”

3. SHAPE MATTERS.

Seashells can be plain and smooth (think clamshells) or come adorned with spikes and ridges and protrusions. Both shapes serve a purpose. Elaborate shells come from the tropics, where predation is fierce. Geerat Vermeij, professor of paleoecology at UC Davis and author of A Natural History of Shells, believes that mollusks in the tropics evolved these ornaments to ward of predators—a much better option than creating a big, thick shell, which will keep predators at bay but is also a pain to make and drag around. He also thinks that “the pleats and corrugations on many tropical shells are a cost-effective way of creating a strong body armor that’s difficult to break into while keeping the weight down,” Scales writes. "Thickening and flaring out the aperature of seashells is another way of deterring predators.”

Sleeker mollusks, meanwhile, can use their streamlined shape to move without detection and to get away quickly. A shell’s shape can also keep the mollusk from sinking in sand and mud, or to keep them anchored in it.

4. THE PATTERNS ON SHELLS AREN’T RANDOM.

Recent research suggests that the elaborate colors and patterns on shells are, Scales writes, “not frivolous playthings but important registration markers for shell-making that have been subject to the forces of natural selection, and have evolved over time.” In other words, mollusks might use the patterns to figure out where to put their mantles to continue making their shells. Scientists still aren’t sure what kinds of pigments the mollusks are using.

5. THE OLDEST KNOWN HERMIT CRAB USED AN AMMONITE SHELL.

There are nearly 1000 species of hermit crab existing today, which rely on old seashells from dead mollusks to protect their soft abdomens. (Interestingly, according to Scales, hermit crabs never kill the current occupants of the shells; they wait until the mollusk has died, and let other animals do the eating, before they take over.) The oldest known hermit crab fossil was discovered in 2002, in the Yorkshire, England village of Steepton. Paleontologist Rene Fraaije spotted the crab in the shell, which, Scales writes, belongs to an ammonite, “an extinct cephalopod that swam through far more ancient seas, in the Lower Cretaceous around 130 million years ago. After it died it sank down to the seabed where a crab scuttled past, picked it up and climbed inside.” It’s the only one found in an ammonite so far.

6. NO TWO ARGONAUT SHELLS ARE THE SAME.

For a long time, scientists believed that argonauts stole their thin, iridescent shells from other animals. Jeanne Power, who invented the aquarium in 1832 so she could study argonauts, discovered that the animals are born without shells and, when they reach about the size of a pinky nail, begin to make their shells. But unlike other mollusks, which secrete their shells with their mantles, female argonauts use glands in two of their arms to make, and repair, their shells. (Male argonauts don’t make shells.) Because of all that repair work, no two argonaut shells are the same.

Argonauts—the only octopuses that still have a shell—can come completely out of their shells, which have ribs and ridges that reduce drag as they move through the water. They use their suckers to hang on, and they’ll never completely abandon their shells. If you take its shell away, an argonaut will die.

7. ONE OF THE OLDEST KNOWN SHELL COLLECTIONS WAS FOUND AT POMPEII.

The collection was preserved in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD and consisted of “shells that came from distant seas, certainly as far as the Red Sea, that seem to have been kept for the simple reason that they looked pretty,” Scales writes.

8. THAT SHELL YOU BOUGHT ON VACATION? IT WASN’T COLLECTED ON A BEACH.

“Plenty of shells are left behind by mollusks that died of disease, predation, old age, or some other fate, but those ones don’t stay pristine for long,” Scales writes. “Chances are that your gleaming shell was taken from a living animal; it was collected and killed and its shell removed and sold into the shell trade, so that ultimately you could buy it.” No one is sure how many shells are traded each year, though it’s thought that around 5000 species of mollusk are targeted. And that trade is very likely affecting wild populations; in some areas, species of mollusk have smaller shells than they did in the past, “a strong indication that not all is well and the larger specimens have been depleted.” When buying shells, be sure to avoid large species like the nautilus (which take a long time to reach maturity, don’t have many young, and are already over-hunted)—or don’t buy at all.