The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 197th installment in the series.

August 12, 1915: A Sinister Influence

The Austro-German offensive unleashed in May 1915 drove forward relentlessly with new campaigns in June and July, before reaching its climax with the collapse of the Russian frontline and the occupation of Poland in August. Warsaw fell on August 4, followed by three key fortress towns – Ivangorod, Kovno (Kaunas), and Novogeorgievsk – on August 5, August 19, and August 20, respectively. Describing the final days of the siege of Kovno one observer, the Polish Princess Catherine Radziwill, wrote that “the cannonade surpassed in intensity anything ever experienced before. The firing was heard farther than Vilna, and carried terror into the hearts of the unfortunate inhabitants of the country surrounding the besieged town.”

The Russian losses in the first year of war were breathtaking: according to some estimates, by the end of August 1915 the Russians had suffered over 3.7 million total casualties, including 733,000 men killed and up to 1.8 million taken prisoner. Meanwhile the empire’s territorial losses included all of “Congress Poland,” with an area of 49,000 square miles and a population of 13 million, equal to 10% of the empire’s total population, as well as most of the Baltic provinces of Courland and Livonia, now known as Lithuania and Latvia. And still the armies of the Central Powers pressed on, into what is now Belorussia and western Ukraine.

As the Russian Army continued its “Great Retreat,” the blame game was heating up on the home front, and as always in Russia conspiracy theories abounded, accusing key figures of incompetence and even treason. Radziwill quoted a letter from a friend in Petrograd: “I do not know what impression the fall of Kovno may have produced abroad. Here the consternation surpasses everything I have ever seen before… The impression that lies have been told is possessing the mind of the public, which begins to say definitely that somebody has been guilty of systematic deceit.”

At the end of June War Minister Vladimir Sukhomlinov resigned amid insinuations of disloyalty, after totally failing to address critical shortages of artillery shells and rifles. Of course these shortages couldn’t be remedied right away; on August 4, Foreign Minister Sazonov summed up the disastrous situation for the French ambassador, Maurice Paleologue: “What on earth shall we do? We need 1,500,000 rifles merely to arm the regiments at the front. We’re producing only 50,000 a month. And how can we instruct our depots and recruits?” A day later, Paleologue described mounting fury in the Russian Duma, or parliament:

Whether in public or secret session there is a constant and implacable diatribe against the conduct of the war. All the faults of the bureaucracy are being denounced and all the vices of Tsarism forced into the limelight. The same conclusion recurs like a refrain: “Enough of lies! Enough of crimes! Reforms! Retribution! We must transform the system from top to bottom!”

On August 12, 1915, Ruth Pierce, a young American woman in Kiev, noted the rumors of treachery circulating alongside news of incredible losses from the front:

They say there was no ammunition at the front. No shells for the soldiers. They had nothing to do but retreat. And now? They are still retreating, fighting with empty guns and clubs and even their naked hands. And still, trainloads of soldiers go out of Kiev every day without a gun in their hands. What a butchery!... How can the soldiers give their lives so patiently and bravely for a Government whose villainy and corruption take no account of the significance of their sacrifices. The German influence is still strong. They say German money bribes the Ministers at home and the generals at the front.

Indeed, more political casualties would soon follow. Unsurprisingly many critics singled out Russia’s top general, the Grand Duke Nicholas, prompting the Tsar’s momentous, ill-fated decision to relieve his uncle of command and personally direct Russia’s war efforts from now on. However many Russians – aristocrats and ordinary folk alike – blamed a dark, malign presence in the royal court: the mysterious monk named Rasputin.

The Dark Monk

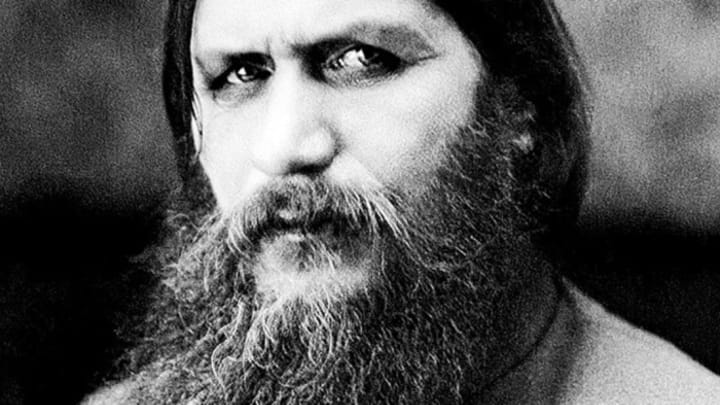

Born in 1869 into a Siberian peasant family, Grigori Rasputin was just one of two out of nine siblings to survive into adulthood. A loner marked by his strange manner and unusual appearance, Rasputin soon became known for his mystic beliefs and supposed miraculous abilities, his charismatic personality amplified by his captivating voice and intense, “penetrating” gaze. After marrying at the age of 18, Rasputin had several children but then suddenly abandoned his family in 1892 and retreated to a monastery, where he embraced his own unusual vision of Orthodox Christianity.

Although often called the “mad monk” or a “holy fool,” Rasputin was actually an itinerant holy man, part of a long Russian tradition of religious wanderers who crisscrossed the empire’s vast expanses, seeking enlightenment through visits to renowned teachers, holy places, and sacred relics. Rasputin soon gained a reputation for his intriguing interpretations of Scripture, expostulated in long sermons delivered, apparently extemporaneously, in his strange Siberian dialect.

Introduced to high society, Rasputin soon gained followers among Russian aristocrats, especially women, who seemed especially entranced by the rough-hewn mystic from the east. In fact “entranced” may be the best word to describe his effect on them: many contemporaries claimed that Rasputin could hypnotize people simply by looking into their eyes. When he was finally introduced to the Tsarina Alexandra in November 1905, he found another willing acolyte – rendered particularly vulnerable to mystic suggestion by her troubled family life.

Most notably, Alexandra’s son Alexei – the heir to the throne – suffered from hemophilia, probably due to centuries of royal inbreeding by the crowned heads of Europe. In 1907 Rasputin supposedly saved the Tsarevich’s life during a bout of uncontrollable bleeding through prayer. In subsequent years the Tsarina would turn to Rasputin again and again for his healing power and holy wisdom, urging her husband Tsar Nicholas II to do the same (below, Alexandra and her children with Rasputin in 1908).

As always in court life, an outsider with special access to the sovereign soon attracted hostile attention from other courtiers, who felt excluded. Rumors began to circulate about the unkempt holy man’s depravity: supposedly he engaged in orgies with his many female followers, taking the virtue of aristocratic women unhinged by religious ecstasy. Some even suggested he was Alexandra’s lover. Whatever the truth of these allegations (no evidence has ever been presented either way) they reflected both Rasputin’s psychological hold on the unstable empress, and the growing hatred and distrust of him in the rest of Russian society. However his opponents were powerless, for now at least, because of Alexandra’s protection; in May 1914 a failed assassination attempt against Rasputin only served to convince the Tsarina of his holiness.

After war broke out in August 1914, Rasputin wielded more and more power over the empress, who now spent long periods away from her beloved husband, leaving her in the company of the persuasive holy man and his other followers. Members of the court who tried to warn Tsar Nicholas II against Rasputin’s growing influence, including the Grand Duke Nicholas, found themselves the object of whispered accusations, as Alexandra (at Rasputin’s behest) gradually undermined the Tsar’s trust in them.

By the summer of 1915, the disastrous military situation gave the Tsarina and Rasputin the perfect opportunity to finally remove the hated Grand Duke Nicholas from power. Almost certainly at Rasputin’s suggestion, the Tsarina urged her husband to remove his uncle from command and take his place as the commander-in-chief of the Russian armies. In one typical note she encouraged his autocratic tendencies and implied that the Grand Duke was out of favor with God himself because of his dislike of Rasputin: “Sweetheart needs pushing always & to be reminded that he is the Emperor & can do whatsoever pleases him… I have absolutely no faith in N – know him to be far from clever and, having gone against a Man of God, his word can’t be blessed.”

By mid-August it would appear Tsar Nicholas II finally succumbed to his wife’s endless campaign against the Grand Duke, despite the advice of literally everyone else in his own inner circle. In a diary entry on August 12, 1915 the tsar’s mother, the dowager empress Maria, wrote of her own shock: “He started to talk about assuming supreme command instead of Nikolai. I was so horrified I almost had a stroke… I added that if he did it, everyone would think it was at Rasputin’s bidding…”

The tsar’s mother was right to be horrified. By taking personal command of the Russian armies, the monarch would be absent from Petrograd, where only he could direct the affairs of government and manage political relations with an increasingly obstreperous Duma; disastrously he planned to put his German-born wife, already widely distrusted because of her supposed German sympathies, in charge of day-to-day administration. He also left her even more under the influence of Rasputin, who was soon rumored to be the third most powerful person in the empire, after the royal couple themselves. Finally, as commander-in-chief Nicholas II would now be directly responsible for any future military reverses. It was with good reason that Sazonov noted, “The Tsar's sudden decision to remove the Grand Duke Nicholas from the Supreme Command and to take his place at the head of the Army caused a great outburst of public anxiety.”

Tragically, last-ditch attempts to counter Rasputin’s influence came to naught: on August 19, 1915 two of his most determined political opponents, chief of the royal chancery Prince Vladimir Orlov and the former governor of Moscow, Vladimir Dzhunkovsky, were relieved of duty after publishing a newspaper article exposing Rasputin’s relationship with the Tsarina. Meanwhile the Tsar’s own Council of Ministers sent a letter to the Tsar, protesting: “We venture once more to tell you that to the best of our judgment your decision threatens with serious consequences Russia, your dynasty and your person.” The ministers repeated their protest in person at a meeting with Tsar Nicholas II at the royal retreat in Tsarskoe Selo on August 21, where the powerful agriculture minister, Krivoshein, warned that the empire was “rolling down the hill not only towards a military but towards an internal catastrophe.”

But the monarch brushed these objections aside, once again at the urging of the Tsarina Alexandra, who argued that it would set a terrible precedent to bend to the will of his cabinet or the Duma: “The Tsar cannot yield. He will only be asked to surrender something more. Where will it end? What power will be left the Tsar?” On August 23 Nicholas II officially dismissed Grand Duke Nicholas, who was sent to take command of the Russian forces facing the Turks in the Caucasus (still a very important position, but a demotion nonetheless). From now on the Tsar would spend almost all his time isolated at the supreme military command headquarters, or Stavka, located at the provincial town of Mogilev – while the situation in the Russian capital slid towards chaos.

See the previous installment or all entries.