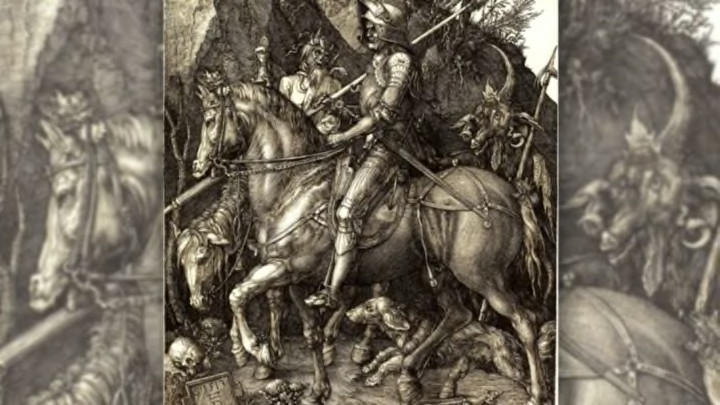

A visual feast and technical marvel, Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil caused a sensation in 16th century Europe and still inspires awe today. But do you know the secrets hidden in its scratches?

1. IT'S NOT A DRAWING.

While it may look like a drawing at first glance, the work is actually a delicately detailed engraving. Printmakers like Dürer used a burin (a "cold chisel") to scratch a hard, flat surface (in this case copper), creating a printing plate. These chiseled niches would hold ink on which paper would be pressed to create a print like Knight, Death, and the Devil (or Ritter, Tod, und Teufel in Dürer’s native German).

2. IT'S PART OF DüRER'S MEISTERSTICHE SERIES.

There's no evidence to suggest Dürer saw Saint Jerome in His Study, Melancholia I, and Knight, Death, and the Devil as companion pieces, but modern art experts group the works because of their technical similarities. Each was created from copper printing plates between 1513 and 1514. They are similar in size and use of contrast, and as you'd expect of pieces called Meisterstiche (or Master Engravings), each is densely detailed with an expert care.

3. THE MEISTERSTICHE SERIES' MEANING IS AN ONGOING SOURCE OF DEBATE.

Despite Dürer not seeing them as a series, some art experts claim Meisterstiche illustrate attributes of medieval scholasticism: theological, intellectual, and moral. Others posit each relates to a stage of mourning "from stoicism (Knight, Death, and the Devil's), to denial (Saint Jerome in His Study) to nightmarish despair (Melancholia I)” in a reflection of Dürer's grief over his mother's death in 1513.

4. DüRER DIDN'T CALL IT KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL.

When the 42-year-old artist completed the engraving in 1513, he called the piece The Rider.

5. KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL MAY HAVE BEEN INSPIRED BY SCRIPTURE.

The three titular figures in this dark scene are believed to illustrate Psalm 23: "Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”

6. OR ERASMUS'S WORK MAY HAVE SERVED AS MUSE.

Some historians argue the Dutch Catholic priest's 1501 book Handbook of a Christian Soldier may have inspired Knight, Death, and the Devil's horseman. One particular passage seems to suit the knight's firm-chinned stare:

"In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary … and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies—the flesh, the devil, and the world—this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil's Aeneas … Look not behind thee."

7. A VENETIAN MONUMENT MAY ALSO HAVE PLAYED A ROLE.

Italian sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio's equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni bears a striking similarity in pose and accouterment to the engraving's noble knight. Erected in 1496, the statue could have been seen and sketched by Dürer when he visited Venice circa 1505-1507.

8. KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL SPEAKS TO DüRER'S OWN FEARS.

Death had lingered around Dürer since he was a child. Of his 17 siblings, only two lived to adulthood. Outbreaks of disease urged him to write, "Anyone who is among us today, may be buried tomorrow," and, “Always seek grace, as if you might die any moment.” Death was a very real and constant threat for the artist, whose devotion to his faith also meant he greatly feared damnation. Knowing this preoccupation, an observer could read Knight, Death, and the Devil as one of the artist's more oblique self-portraits.

9. THE ENGRAVING IS PACKED WITH SYMBOLS.

Snake-shrouded Death and the goat-faced Devil speak for themselves. But the work is loaded with other symbols. The knight's shining armor is believed to signify his solid Christian faith. The hourglass in Death's hand represents man's mortality. The foxtail speared on the knight's lance and kept behind him stands for lies, while the dog running alongside represents veracity and loyalty. The scurrying lizard hints at coming danger. The skull near the bottom may mean death is ahead.

10. DüRER WORKED A COPYRIGHT INTO THE COMPOSITION.

Rather than crudely cutting a signature into the piece (as some impetuous artists might do), the German printmaker incorporated his initials and the date onto a plaque in the picture's lower left side. The way he carved his "AD" served as a sort of logo that allowed him to protect his rights to the sales of his prints as they made their way across Europe.

11. IT'S QUITE SMALL.

Although the work is categorized as a "large print" by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Knight, Death, and the Devil measures in at just 9.6 by 7.5 inches.

12. JORGE LUIS BORGES PENNED TWO POEMS ABOUT THIS PIECE.

Named "Ritter, Tod, und Teufel" (I) and "Ritter, Tod und Teufel" (II), the first shows the Argentine author's admiration for the knight's bravery in the face of death and damnation, while the second reveals he can see himself in that very position.

13. YOU CAN FIND IT IN MUSEUMS ALL OVER AMERICA.

Historians don’t know how many prints Dürer issued of Knight, Death, and the Devil. But several American museums have one in their collection, including the Met, Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, the University of Kansas' Spencer Museum of Art, and the Glessner House Museum.

14. SOMETIMES THEY CAN EVEN BE FOUND IN PAWNSHOPS.

In a 2011 episode of the reality TV series Pawn Stars, Las Vegas pawnbroker Rick Harrison purchased a Knight, Death, and the Devil print for $5500. The expert appraisal suggested he could fetch $20,000 to $50,000 at auction for the rare engraving.

15. PRINTS LIKE THESE HAVE MADE DüRER FAMOUS AND POWERFUL.

Within a few years of Knight, Death, and the Devil's creation, Dürer was one of the most in-demand artists of northern Europe. He boldly rejected job offers to become a court painter and even dismissed those artists as "parasites.” Instead, he moved away from painting to focus on printmaking, churning out hundreds of prints to be sold across the continent. This replication sparked a revolution that made owning art accessible for the masses. While Knight, Death, and the Devil commanded "the cost of a rabbit-fur coat," lesser-known Dürer engravings could be had at much lower prices.

Rather than relying on—and sharing the profits with—a publisher, Dürer employed assistants at his own printing press, propping up ravenous demand in a developing print market. Meanwhile, his keen eye for detail and remarkable carving helped elevate the medium of printmaking from folk art to fine art. Ultimately, his incredible engravings have made him the most famous artist of the German Renaissance.