We're currently in the midst of a pretty intense El Niño. Here are a few things you might not have known about the weather phenomenon—and what we can expect from this year's incarnation.

1. EL Niño MEANS “THE LITTLE BOY” or “CHRIST CHILD.”

In 1892, a Peruvian naval captain named Camilo Carrillo reported on an abnormally warm current that ran along the western coast of South America. As he explained to his government, it usually showed up around Christmastime and remained for several months. So, in honor of Jesus’s birth, fishermen from Peru and Ecuador nicknamed it El Niño.

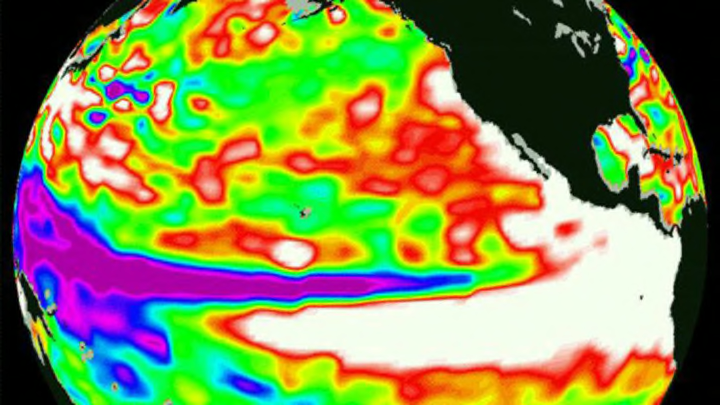

As the years went by, the term’s definition changed. Currently, in North America (other regions are broadly similar), El Niño is defined as “a five consecutive three-month running mean of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region that is above the threshold of +0.5°C.” In English, this means that the average temperature of the water is half a degree higher than normal for five months in a region of the Pacific about halfway between Peru and Papua New Guinea. In certain areas, this triggers an increase in precipitation, floods, and hurricanes.

2. IT'S PART OF A LARGER CYCLE.

Surface winds (also known as trade winds) normally blow across the Pacific from east to west. This pushes warmer, sun-heated water toward Asia while cooler H2O rises up from the depths near North and South America. The line of motion also means that the sea’s surface is generally about half a meter higher over by Indonesia than it is around Ecuador.

But sometimes, those winds are too weak to do their job. When that happens, the eastern Pacific becomes unusually warm, while the west suffers through a cold spell—and you get an El Niño. Conversely, extra-strong trade winds make the Pacific really, really cool, as even more cold water is coming from the depths. Such occurrences are called La Niña, or “the Little Girl.”

El Niño and La Niña represent two sides of the same coin. Each is a phase in a larger cycle known as El Niño Southern Oscillation (or ENSO). Ordinarily, the former stage lasts for nine to 12 months, while the latter has a one- to three-year lifespan.

3. WE'VE IDENTIFIED A FEW DISTINCT TYPES.

No two El Niños are exactly alike. In recent years, climate experts have noticed that they can come in several different varieties. The kind described above is a Conventional or Eastern Pacific El Niño. Every so often, though, you’ll wind up with a Central Pacific El Niño, which warms the mid-Pacific to a greater degree than the east or west. It looks like there’s an entire spectrum of El Niños beyond these simplistic categories.

4. EL Niños TEND TO CREATE SEVERE AUSTRALIAN DROUGHTS.

Down under, most extreme dry periods have been associated with an El Niño—but it’s hard to predict exactly how badly Australia’s rainfall will be affected by any given one. During the 1997-’98 El Niño (which was the 20th century’s strongest), significant drops in precipitation only took place in eastern Australia and Tasmania. Years later, though, the rather mild 2002-’03 El Niño sparked an enormous, nationwide drought.

5. THEY PROBABLY HELP SPREAD MOSQUITO-BORNE DISEASES.

In the early 20th century, the Punjab region of India was site of regular malaria epidemics, and, according to the World Health Organization, “recent analyses have shown that the malaria epidemic risk increases around five-fold in the year after an El Niño event” (similar observations were made in Sri Lanka). At present, the number of malaria-infected Venezuelans and Columbians goes up by 33 percent after an El Niño. Other mosquito-transmitted ailments—like Rift Valley fever and dengue—also experience a post-El Niño boom.

6. ONE SURVEY FOUND THAT EL Niño MIGHT PROVOKE CIVIL WARS.

In 2011, Columbia University economist Solomon Hsiang and two colleagues reviewed 234 civil wars that have broken out in some 175 countries since 1950 and uncovered a disturbing pattern: Tropical countries were twice as likely to have a skirmish in years that had been preceded by an El Niño. According to Hsiang, “Since 1950, one out of five civil conflicts have been influenced by El Niño.” Why is this so? Droughts caused by the weather phenomena may be partly responsible, as they tend to exacerbate longstanding food shortages. “This represents the first major evidence that global climate is a major factor in organized patterns of violence,” Hsiang says.

7. EL Niño FORCES SEA BIRDS TO WIND UP IN UNUSUAL PLACES.

Peruvian boobies aren't usually found as far north as Panama. Under normal circumstances, the birds hunt anchovies off the coasts of Chile, Ecuador, and—of course—Peru. But regional fish populations take a big hit during El Niño, forcing some avians to seek food elsewhere. Early in 2014, El Niño-like conditions broke out, and by that July, several transplanted boobies had been spotted in Panama. Similarly, they descended on the country after the 1982-’83 El Niño, with 3500 roosting on Pachecha Island alone.

8. MIDWESTERN TORNADOES BECOME LESS COMMON DURING EL Niño.

On the plus side, El Niño years make life a little easier in the plains states. La Niña warms and moistens wind currents that regularly swing upwards from the Gulf of Mexico—thus increasing the local tornado tally. Meanwhile, an El Niño has the opposite effect.

9. AN 1876 EL Niño CREATED A DROUGHT THAT KILLED 18 MILLION PEOPLE.

Wikimedia Commons // Public domain

In 1876, an intense El Niño-triggered dry spell broke out in India and north China. Throughout both areas, crops were decimated, and—due to the weakening of central government in China and colonial trade policies in India—neither government was adequately prepared for the disaster. As a result, roughly 12 million Chinese and 6 million Indians had died of hunger by 1879.

10. THE 1982-’83 MODEL COST THE GLOBAL ECONOMY OVER $8 BILLION.

Indonesia and Australia were hit with forest fires. Large typhoons struck Hawaii and Tahiti. A mass exodus of sardines had a major impact on the fishing industry in Ecuador and Peru. There was extensive flooding in the southern U.S. It was not a great time for international commerce.

11. CERTAIN ECONOMIES ACTUALLY BENEFIT FROM THEM.

Following the 2010 El Niño, Argentina’s GDP rose by 1.08 percent, Canada’s by 0.85 percent, and Mexico’s by 1.57 percent. How did that happen? The El Niño led to a decrease in east coast hurricanes, which was great for the Mexican oil industry. A warm weather influx meant that Canada’s fisheries could yield a greater output. Finally, heightened precipitation helped Argentinian soybean growers.

12. ONE CALIFORNIAN WAS WRONGLY BLAMED FOR THE 1997-’98 EL Niño.

A few months into the 1997-'98 El Niño, one resident of Nipomo, California began to get weird phone calls. “It was always something like, ‘Why are you doing this?’” he remembers. One person politely asked the retired submarine crewman to steer clear of Cayucos. Another screamed obscenity after obscenity at 2 a.m. Before the whole thing blew over, David Letterman contacted him with an invitation to appear on The Late Show.

The man’s name? Alfonso Niño. In the phonebook, he was listed as Al.

13. THEY'RE BECOMING MORE COMMON.

Climatologists largely agree that the frequency of El Niños is rising—and they might be getting stronger. Of the 20th century’s 23 El Niños, the four most powerful all took place after 1980.

14. SO FAR, THE 2015 SEASON HAS BEEN INTENSE.

Combing the El Niño archives can tell us some interesting things about the one we’re now experiencing. For example, the average August-through-October sea surface temperature is the second-highest on record, exceeded only by what was documented during the 1997 El Niño.

Another tool tells a similar story. The Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI) is a standard unit of measurement that records the mean sea level pressure from Indonesia to the eastern Pacific. According to recent EQSOI data, only the 1997 El Niño was more extreme than 2015’s is. And according to NOAA, it’s already having global impacts, including flooding in Somalia, a very dry Southern Africa, coral bleaching, and increased forest fires in Indonesia (the most since 1997). They also say that the United States won’t know the full effect until spring next year.