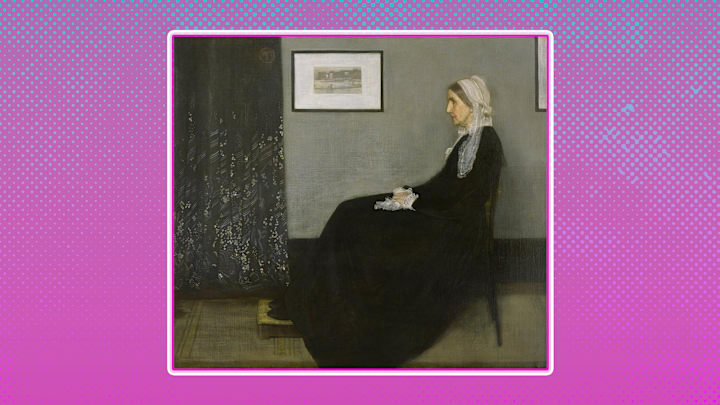

American artist James McNeill Whistler is best remembered for his portrait of his beloved mother, fittingly known as Whistler’s Mother. But while affection grew for this painting, its true intentions—and even its real name—got lost.

- Whistler painted it on a whim.

- Whistler’s mother originally stood in the painting.

- It’s bigger than you may think.

- Whistler didn’t call the piece Whistler’s Mother.

- Whistler’s mother was one of his biggest fans.

- American audiences got a good look at the painting during the Great Depression.

- The painting played a role in World War I.

- Whistler’s Mother received mixed reviews.

- The Royal Academy initially rejected it.

- An iconic museum redeemed the painting’s reputation.

- Different museums have hosted the painting over the years.

- Whistler designed the frame, too.

- Whistler’s Mother has a companion piece.

- It has become one of the most famous American artworks overseas.

Whistler painted it on a whim.

In 1871, the Massachusetts-born painter had received a commission from a member of Parliament to paint his daughter, Maggie Graham. When several sittings failed to provide any form of a finished painting, Maggie flaked on Whistler after he had already prepared a canvas, so he asked his mother to literally stand in. Or, as his mother explained in one of many letters that unintentionally wrote the history of this piece, “If the youthful Maggie had not failed Jemie,” as she called her son, “in the picture which I trust he may yet finish from Mr. Grahame [sic], he would have had no time for my portrait.”

Whistler’s mother originally stood in the painting.

Standing still for long stretches proved difficult for the aging lady, and she later wrote to her sister, “I stood bravely, two or three days, whenever he was in the mood for studying me as his pictures are studies, and I so interested stood as a statue! But realized it to be too great an effort, so my dear patient Artist who is gently patient as he is never wearying in his perseverance concluding to paint me sitting perfectly at my ease.”

It’s bigger than you may think.

With the entire painting measuring 56.8 inches by 64.2 inches, Whistler’s mother is almost life-size within the frame.

Whistler didn’t call the piece Whistler’s Mother.

Following a theme of naming his paintings like musical compositions, Whistler dubbed this portraitArrangement in Grey and Black - Portrait of the Painter’s Mother. Eventually, it became known as Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1. Whistler’s Mother is a nickname popularized by the public.

Whistler’s mother was one of his biggest fans.

A true Victorian, Anna McNeill Whistler was religious and always tried to be a good housewife and mother. After being widowed at 45, she was deeply devoted to her surviving children. In 1864, she moved to London to be closer to them, eventually becoming aware of James’s bohemian lifestyle. Though we might assume the debauchery of that life would fluster the devout mum, she supported her son by being his model, his caretaker, and even on occasion his art agent. Anna once wrote of him, “The artistic circle in which he is only too popular, is visionary and unreal tho so fascinating. God answered my prayers for his welfare by leading me here.”

American audiences got a good look at the painting during the Great Depression.

During the Depression, the painting traveled America in a 13-city tour, which included a stop at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. From this exposure, America fell hard for Whistler's Mother. She was not only featured on a 1934 stamp, but also inspired an 8-foot-tall bronze statue erected high on a hill overlooking Ashland, Pennsylvania. Built by the Ashland Boys’ Association in 1938 as an ode to mothers everywhere, the pedestal of this monument quotes the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, reading, “a mother is the holiest thing alive.”

The painting played a role in World War I.

In 1915, the painting was put on posters distributed by the Irish Canadian Rangers 199th Overseas Battalion to encourage volunteers to enlist.

Whistler’s Mother received mixed reviews.

Debuting in London when flamboyance and romanticism were all the rage, Whistler's Mother was not what the art world wanted. The London Times sneered, “An artist who could deal with large masses so grandly might have shown a little less severity, and thrown in a few details of interest without offence.”

Conversely, a Paris critic was modestly impressed, writing, “It was disturbing, mysterious, of a different color from those we are accustomed to seeing. Also the canvas was scarcely covered, its grain almost invisible; the compatibility of the grey and the truly inky black was a joy to the eye, surprised by these unusual harmonies.”

The Royal Academy initially rejected it.

The members of the academy couldn’t wrap their heads around the painting’s perceived severity. But Whistler had an ally in English artist and director of the National Gallery William Boxall, who pushed the academy to reconsider, and the academy ultimately accepted Whistler's Mother, albeit begrudgingly. While the portrait hung in their esteemed halls, it was tucked away in a poor location. Whistler felt this burn so much that he never submitted another work to the academy.

An iconic museum redeemed the painting’s reputation.

In 1891, the prestigious Parisian museum Musée du Luxembourg purchased the work. Whistler was elated, writing, “Just think—to go and look at one’s own picture hanging on the walls of Luxembourg—remembering how it was treated in England—to be met everywhere with deference and treated with respect … and to know that all this is … a tremendous slap in the face to the academy and the rest! Really it is like a dream.” He was right. Following the Luxembourg’s acquisition, his reputation improved, as did his popularity among patrons.

Different museums have hosted the painting over the years.

Though it has occasionally crossed the sea for American exhibitions, Whistler’s Mother has been the property of the French government for over a century. But its home within France has shifted. In 1922, the painting moved from the Luxembourg to the Louvre. Sixty-four years later, the popular portrait settled in the Musée d’Orsay, which is still its permanent home (when it’s not touring to other museums around the world.)

Whistler designed the frame, too.

The frame’s golden hue reflects the modest gold wedding band on his mother's finger.

Whistler’s Mother has a companion piece.

Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle was one of the few instantly taken by Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1. So, he sat for the lesser known but similarly staged Arrangement in Grey and Black No 2. As Whistler later recounted, “He liked the simplicity of it, the old lady sitting with her hands in her lap, and said he would be painted. And he came one morning soon, and he sat down, and I had the canvas ready, and my brushes and palette, and Carlyle said, ‘And now, mon, fire away!’”

It has become one of the most famous American artworks overseas.

Described as the Victorian Mona Lisa, Whistler’s Mother has become so iconic and so ubiquitous in global culture that it has been favorably compared to The Scream, the actual Mona Lisa, and American Gothic.

Discover More Stories About Art:

A version of this story was published in 2015; it has been updated for 2024.