Six decades years since its premiere on CBS on December 9, 1965, A Charlie Brown Christmas remains one of the most beloved holiday specials of all time. Like Charlie Brown himself, the flaws—scratchy voice recordings, rushed animation—have proven endearing. Take a look at some facts behind the show that killed aluminum trees, the struggles to animate Chuck’s round noggin, and why Willie Mays is the unsung hero of Peanuts.

- Charles Schulz wasn’t really interested in getting into animation.

- Willie Mays played a part in getting it made.

- CBS and Coca-Cola only gave them $76,000 to produce A Charlie Brown Christmas.

- A Charlie Brown Christmas was going to have a laugh track.

- Snoopy’s voice is just sped-up nonsense.

- Charles Schulz hated jazz.

- Charlie Brown’s head was a nightmare to animate.

- Charles Schulz was embarrassed by one scene.

- A Charlie Brown Christmas almost got scrapped by Coke.

- CBS hated A Charlie Brown Christmas.

- Half the country watched A Charlie Brown Christmas.

- A Charlie Brown Christmas killed aluminum tree sales.

- There’s a live-action play version of A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Charles Schulz wasn’t really interested in getting into animation.

Since the debut of Peanuts in 1955, Charles Schulz and United Press Syndicate (which distributed the comic strip) had gotten a steady stream of offers to adapt the characters for film and television; the artist was also directly petitioned by young readers, who would write Schulz asking when Snoopy would come to some kind of animated life. His stock reply: “There are some greater things in the world than TV animated cartoons.”

He relented for Ford Motors—he had only ever driven a Ford—and allowed Charlie Brown to appear in a series of commercials for the Ford Falcon in the early 1960s. The spots were animated by Bill Melendez, who earned Schulz’s favor by keeping the art simple and not using the exaggerated movements of the Disney films—Bambi, Dumbo—Melendez had worked on previously.

Willie Mays played a part in getting it made.

Schulz capitulated to a full-length special based on the professional reputations of his two collaborators. The cartoonist had seen and enjoyed executive producer Lee Mendelson’s documentary on baseball player Willie Mays, A Man Named Mays; when Mendelson proposed a similar project on Schulz and his strip, he agreed—but only if they enlisted Melendez of the Ford commercials. The finished documentary and its brief snippet of animation cemented Schulz’s working relationship with the two and led Schulz to agree when Mendelson called him about a Christmas special.

You May Also Like ...

- Good Grief! 18 Facts About Charles Schulz’s Peanuts Comics

- Charlotte Braun, the Peanuts Character Who Met a Gruesome End

- 10 Facts About Snoopy

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

CBS and Coca-Cola only gave them $76,000 to produce A Charlie Brown Christmas.

When Coke executives got a look at the Schulz documentary and caught Charlie Brown on the April 1965 cover of Time, they inquired about the possibility of sponsoring an hour-long animated holiday special. Melendez felt the short lead time—only six months—made that impossible. Instead, he proposed a half-hour, but had no idea how much the show should be budgeted for; when he called colleague Bill Hanna (of Hanna-Barbera fame) for advice, Hanna refused to give out any trade secrets. Melendez wound up getting a paltry $76,000 to cover production costs. (It evened out: Schulz, Mendelson, and Melendez wound up earning roughly $5 million total for the special through 2000.)

A Charlie Brown Christmas was going to have a laugh track.

In the ‘60s, it was standard procedure to lay a laugh track over virtually any half-hour comedy, even if the performers were drawn in: The Flintstones was among the series that used a canned “studio audience” to help cue viewers for jokes. When Mendelson told Schulz he didn’t see the Peanuts special being any different, the artist got up and left the room for several minutes before coming in and continuing as if nothing had happened. Mendelson got the hint.

Snoopy’s voice is just sped-up nonsense.

The early Peanuts specials made use of both untrained kids and professional actors: Peter Robbins (Charlie Brown) and Christopher Shea (Linus) were working child performers, while the rest of the cast consisted of “regular” kids coached by Melendez in the studio. When Schulz told Melendez that Snoopy couldn’t have any lines in the show—he’s a dog, and Schulz’s dogs didn’t talk—the animator decided to bark and chuff into a microphone himself, then speed up the recording to give it a more emotive quality.

Charles Schulz hated jazz.

The breezy instrumental score by composer Vince Guaraldi would go on to become synonymous with Peanuts animation—but it wasn’t up to Schulz. He left the music decisions to Mendelson, telling a reporter shortly after the special aired that he thought jazz was “awful.”

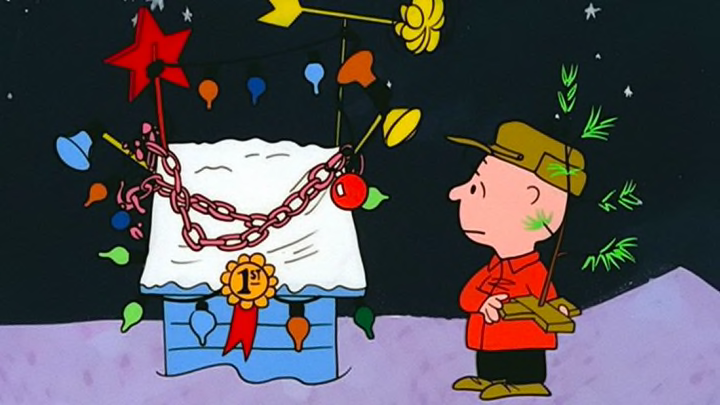

Charlie Brown’s head was a nightmare to animate.

Because Melendez was unwilling to stray from Schulz’s distinctive character designs—which were never intended to be animated—he found himself in a contentious battle with Charlie Brown’s noggin. Its round shape made it difficult to depict Charlie turning around; as with most of the characters, his arms were too tiny to scratch his head. Snoopy, in contrast, was free of a ball-shaped cranium and became the show’s easiest figure to animate.

Charles Schulz was embarrassed by one scene.

Careful (or repeated) viewings of the special reveal a continuity error: in scenes where Charlie Brown is standing near his tree, the branches appear to grow from moment to moment. The goof annoyed Schulz, who blamed the mistake on two animators who didn’t know what the other was doing.

A Charlie Brown Christmas almost got scrapped by Coke.

In 2015, Mendelson told USA Today that an executive from McCann-Erikson—the ad agency behind Coke—paid him an impromptu visit while he was midway through production. Without hearing the music or seeing the finished animation, the ad man thought it looked disastrous and cautioned that if he shared his thoughts with Coca-Cola, they’d pull the plug. Mendelson argued that the charm of Schulz’s characters would come through; the exec kept his opinion to himself.

CBS hated A Charlie Brown Christmas.

After toiling on the special for six months, Melendez and Mendelson screened it for CBS executives just three weeks before it was set to air. The mood in the room was less than enthusiastic: the network found it slow and lacking in energy, telling Melendez they weren’t interested in any more specials. To add insult, someone had misspelled Schulz in the credits, adding a t to his last name. (Schulz himself thought the whole project was a “disaster” due to the crude animation.)

Half the country watched A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Viewers weren’t nearly as cynical about Charlie Brown’s holiday woes as his corporate benefactors. Preempting a 7:30 p.m. EST episode of The Munsters, A Charlie Brown Christmas pulled a 50 share, meaning half of all households with a television turned on were watching it. (That amounted to roughly 15 million people, behind only Bonanza.) CBS finally acknowledged it was a winner, but not without one of the executives getting in one last dig and telling Mendelson that his “aunt in New Jersey didn’t like it.”

A Charlie Brown Christmas killed aluminum tree sales.

Aluminum Christmas trees were marketed beginning in 1958 and enjoyed fairly strong sales by eliminating pesky needles and tree sap. But the annual airings of A Charlie Brown Christmas swayed public thinking: In the special, Charlie Brown refuses to get a fake tree. Viewers began to do the same, and the product was virtually phased out by 1969. The leftovers are now collector’s items.

There’s a live-action play version of A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Up until 2013, anyone staging a live-action rendition of A Charlie Brown Christmas for their local school or theater had one thing in common: they were copyright infringers. The official rights to the story and characters weren’t offered until the 21st century. Concord Theatricals fields licensing requests for the play, which includes permission to perform original songs and advertise with the Peanuts characters—Snoopy costume not included.

A version of this story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2025.