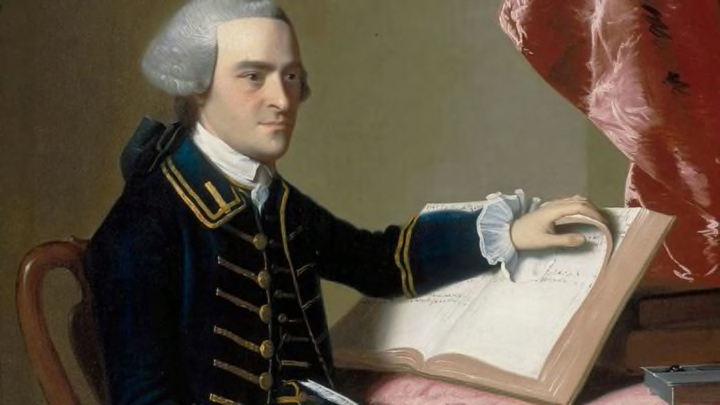

You won’t find his likeness anywhere on American currency. Instead, we’ve given this founding father a linguistic tribute—thanks to one revolutionary document, his very name is now a synonym for signature. Join us as we celebrate this great New England statesman on his birthday.

1. HE WAS ADOPTED BY HIS UNCLE WHEN HE WAS 7.

Born in Braintree, Massachusetts on January 23, 1737 (according to the Gregorian calendar), Hancock was named after his father, the Reverend John Hancock. A Puritan minister, the elder John lived in a manse provided by the congregation he served with his wife, Mary Hawke Thaxter, and their three children; little John was the second. When the Reverend died in 1744, the family found itself homeless, their house promised to his replacement. Mary was moving the family to live with the children’s paternal grandfather, but John wound up under the care of his childless paternal uncle, Thomas Hancock. A powerful Boston merchant, Thomas and his wife, Lydia, handled Mary’s financial needs from afar while raising John as their own son and eventual heir.

2. HE ATTENDED THE CORONATION OF KING GEORGE III.

In 1760, Thomas sent his young protégé to England on a sensitive business trip, where Hancock became a witness to history (though certainly not for the last time). King George II was buried on November 13; among those present at his funeral was 23-year-old Hancock. In a letter to Thomas, the traveler expressed a deep desire to attend another royal event—King George III’s coronation. “I can’t yet determine whether I shall stay to see it,” he wrote, “but rather think I shall, as it is the grandest thing I shall ever meet with.”

Hancock is said to have not only watched the ceremony, but to have been briefly introduced, afterward, to his new monarch—who would one day put a 500-pound bounty on the New Englander.

3. REPORTEDLY, HE WAS A BOSTON TEA PARTY CHEERLEADER.

Hancock himself didn’t take part in the protest, in which Boston natives snuck aboard three British ships on December 16, 1773 and threw 342 chests of East India Company tea overboard—but he was one of the most vocal supporters of the party. George Robert Twelves Hewes, one of the tea-snatchers who illegally boarded the vessels, said that the last thing he recalled of the meeting that preceeded the tea party was Hancock’s shout of “Let every man do what is right in his own eyes.” But some historians think that Hancock’s motives weren’t exactly virtuous; Hancock supposedly made part of his fortune smuggling in Dutch tea, and the Tea Act meant that East India Company tea would be cheaper than the stuff he smuggled in.

4. HANCOCK DESPERATELY WANTED TO FIGHT IN THE BATTLE OF LEXINGTON.

On April 18, 1775, Hancock and fellow revolutionary Samuel Adams were lodging in Lexington, Massachusetts at the former home of Hancock’s grandfather. Little did they know that the shot heard ‘round the world would go off in just a few short hours. On the orders of the British government, General Thomas Gage led 700 red-coated troops to seize a nearby colonial militia’s weapon stockpile—and some believed that he also planned on arresting Adams and Hancock in the process.

Famously, a silversmith named Paul Revere rode out to Lexington that night, warning locals as he went. Revere arrived late at night and was able to give Hancock and Adams the warning, after which he continued to Concord. But on the way he was temporarily detained by the Brits, and after being released, he went back to make sure that Hancock and Adams had indeed escaped.

But to Revere's surprise, Hancock hadn't left. Instead, he loudly insisted on staying put and fighting alongside the militiamen. “If I had my musket,” he said, “I would never turn my back on these troops.” Eventually, Revere and Adams convinced him to flee, arguing that the British would score a huge moral victory by jailing such an influential patriot. This wasn’t an easy sell. As eyewitness Dorothy Quincy—Hancock’s fiancée—noted, “it was not until break of day that Mr. H. could be persuaded.”

5. HIS IS, BY FAR, THE BIGGEST SIGNATURE ON THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

At the time, Hancock was acting President of the Second Continental Congress. As such, he was first to sign Thomas Jefferson’s monumental declaration in July 1776. The first printed copies bear only Hancock’s signature and that of Secretary Charles Thompson. These typeset documents were mailed out to the colonies before an identical, handwritten version was created. Eventually, this copy—now on display at the National Archive—acquired 56 signatures, most of which were jotted down on August 2.

You’ll notice immediately that Hancock’s signature dwarfs the competition. The vast majority take up somewhere between one and 2.5 square inches. At a whopping 6.1 square inches, however, Hancock’s signature is the biggest by far. Why did he upstage everyone else? Historians aren’t sure.

Nevertheless, we can at least dispel one common myth about the subject. Popular rumor holds that when Hancock left his extra-large signature, he defiantly shouted “There, I guess King George will be able to read that!” But there’s no confirmed record of him ever actually saying this.

6. HE WAS THE FIRST ELECTED GOVERNOR OF MASSACHUSETTS.

Hancock won the Bay State’s highest office in 1780, claiming more than 90 percent of the vote. He went on to earn five one-year terms before unexpectedly resigning in 1785. Following Shay’s Rebellion, Hancock re-entered the ring, winning yet another gubernatorial race. This time, he held the job he until died in 1793 at age 56.

7. IN 1789, HANCOCK WAS A PRESIDENTIAL “ALSO RAN.”

American politics will probably never see another landslide of this magnitude. In the nation’s first presidential election, beloved war hero George Washington prevailed with a showing for the ages. By constitutional law, each elector was granted two votes. Every single participant cast at least one of these for the General. At day’s end, Washington secured 69 total votes. By comparison, second-place-finisher John Adams nabbed a meager 34. Nobody else even broke single digits—John Jay took home nine, Robert Harrison and John Rutledge each received six, Hancock claimed four, George Clinton netted three, and two apiece went to Samuel Huntington and John Milton. As for the remaining three votes, they were divvied up between as many candidates.

8. HE AND SAMUEL ADAMS HAD A HUGE FALLING OUT.

Early on, Adams, a politician and brewer, saw Hancock as an impressive protégé. Here was a powerful, ambitious fellow upon whom several hundred families were dependent for their livelihoods. In 1766, Adams used his influence to help win the businessman a seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. There, Hancock quickly established himself as one of Britain’s most vocal detractors in the colony.

When the hated Stamp Act was repealed on March 20, 1766, Hancock received much of the credit. In short order, Adams and his supporters—whom he called the “Sons of Liberty”—rushed en masse to their hero’s home. Elated, Hancock surprised the crowd with 125 gallons of free Madeira wine.

Sadly, the once warm Adams-Hancock partnership soon chilled. After George Washington was appointed commander-in-chief of the continental army in 1775, Hancock—who had longed for the job—suspected that Adams had helped tip the scales against him. At the time, Hancock was acting as President of the Second Continental Congress. Upon stepping down from that post, Adams and the rest of the Massachusetts delegation infuriated him by voting against a resolution that would thank Hancock for his service. Things soured still further once Hancock became governor of his home state—and Adams routinely backed his opponents.

Nevertheless, the estranged pair did come together to endorse the new U.S. Constitution in 1787. Furthermore, when Hancock died, it was Lieutenant Governor Adams who took over the gubernatorial position. By order of his friend-turned-foe, the day of Hancock’s burial was solemnly observed as a state holiday.

9. HE WAGED A DECADES-LONG WAR WITH GOUT.

Hancock developed the illness when he was 36. As years went by, his limbs were severely handicapped by the condition—when President Washington visited the Bay State in 1789, the 53-year-old governor had to be carried out to greet him.

10. BOSTON’S TALLEST TOWER WAS NAMED IN HIS HONOR.

This 60-story, glass-sided structure also happens to be the tallest building in all of New England. The establishment was created by John Hancock Financial Services—a company named after the legendary patriot. Built in 1976, the establishment had been officially called “John Hancock Tower” until the company's lease ran out last July. Since then, it’s been re-branded as 200 Clarendon, though many Bostonians persist in using the older name.