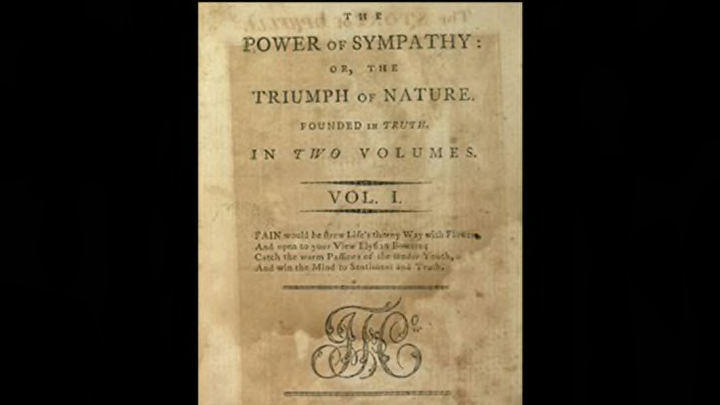

On this date in 1789, Boston bookseller Isaiah Thomas and Company published The Power of Sympathy: or, The Triumph of Nature. Released just six years after the official end of the Revolutionary War, the book—a cautionary tome, published in two volumes, about the dangers of giving in to passion and featuring unwitting incest and suicide—is generally considered to be the first American novel. Within its pages, the author not only defended novels as a whole—which, at the time, were thought to be morally bereft—but also his novel, promising that it was moral as could be: “The dangerous consequences of SEDUCTION are exposed,” the author wrote, and the "Advantages of FEMALE EDUCATION set forth and recommended.” Here are a few things you might not have known about the book.

1. IT’S A TEXTBOOK EXAMPLE OF AN 18TH CENTURY WRITING DEVICE.

The Power of Sympathy is a book written as a series of letters between characters, a type of literary device known as the epistolary technique. Other examples of the form—which was popular from the 18th century right up to the present day and could include any type of document, from diary entries to newspaper clippings—include Clarissa (1748), Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782), and Dracula (1897).

2. ONE PLOTLINE WAS VERY SIMILAR TO A LOCAL SCANDAL.

Just five months before Sympathy was published, Boston resident Fanny Apthorp committed suicide, and her reasons for doing so became a central plotline in the first volume of the book. The location of the scandal was changed from Boston to Rhode Island, and its participants were given new monikers—but according to William S. Kable, then an associate professor of English at the University of South Carolina who wrote the introduction to a 1969 edition of Sympathy, that only “[threw] a very thin veil of fiction” over the actual scandal [PDF]:

In the story, Ophelia (Frances Theodora Apthorp) is seduced by her sister’s husband, Martin (Perez Morton). After their illicit relationship produces a child, Ophelia’s father, Shepherd (Charles Apthorp) is bound and determined to bring about a settlement. Just before a scheduled confrontation of the various parties, Ophelia (Fanny) poisons herself.

Morton—a friend of future president John Adams—didn’t appear to suffer from the affair, personally or professionally: He and his wife, Sarah Wentworth Morton, later reconciled, and he served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives just five years after the scandal.

3. IT WAS PUBLISHED ANONYMOUSLY.

There was no name on Sympathy on its initial publication, but the book did have a dedication, which read:

To the Young Ladies, Of United Columbia, Intended to represent the specious causes, And to Explore the fatal Consequences of Seduction; To inspire the female mind With a principle of self complacency And to Promote the Economy of Human Life, Are inscribed, With Esteem and Sincerity, By their Friend and Humble Servant, The Author

4. AFTER PUBLICATION, THE BOOK WAS SUPPRESSED.

Despite the fact that Thomas advertised the book in several papers (the ads read, “This Day Published THE POWER OF SYMPATHY, OR THE TRIUMPH OF NATURE, The First American Novel”) and released two versions (a version bound in calf leather for 9 shillings, and one in blue paper for 6), Milton Ellis, co-author of Philenia: the Life and Works of Mrs. Sarah Wentworth Morton, wrote in a 1933 issue of American Literature that Sympathy was “little noticed and soon forgotten. Aside from advertisements and two puffs in the Massachusetts Magazine, also published by Isaiah Thomas … it [was] mentioned in print only five times in 1789, only twice between 1790 and 1800, and not at all during the 50 years following.”

That was likely because, at the request of the Mortons and Apthorps—and with the cooperation of the author—publication of the book ceased, and unbought copies were destroyed, to avoid painful rehashing of the scandal. But that effort wasn’t completely successful: Advertisements for the book appeared a few years later, and it was still available for purchase.

5. NEARLY A CENTURY AFTER IT WAS PUBLISHED, IT WAS ATTRIBUTED TO MORTON’S WIFE …

After her husband’s affair, Sarah Wentworth Morton became a widely-published poet; she died in 1846. The rumor that she was the author of Sympathy began in the mid-1800s, but didn’t appear in print until 1878, when historian Francis Samuel Drake said in The Town of Roxbury that “The seduction of a near and dear relative is said to have formed the groundwork of the first American novel, The Power of Sympathy, written by Mrs. Morton.”

In June 1894, the book was reissued; the title page read “By Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp),” and the book’s editor called her the "self-acknowledged author.” Then, in October of that year, Bostonian magazine began publishing the novel in installments; editor Arthur W. Brayley attributed the book to Morton once again.

6. … BUT THE AUTHOR WAS LATER REVEALED TO BE A MAN NAMED WILLIAM HILL BROWN.

By December 1894, however, Brayley had changed his tune and printed a retraction in the Bostonian. What had changed? Eighty-year-old Rebecca Volentine Thompson came forward with new information. She revealed that it was her uncle, William Hill Brown—a neighbor of the Apthorps—who had written Sympathy. Brown, just 24 when Sympathy was released, was likely well aware of the scandal it might cause; not wanting to ruin his future writing prospects, he chose to publish anonymously.

There had been clues that the author was a man. For one, the title page referred to the author as a he (“Fain would he strew Life’s thorny way with flowers …”). And contemporary sources also used the masculine pronoun when referring to the author: According to Ellis, “one calls him an ‘amiable youth’; and one, in alluding to him, substitutes five dashes for the letters of his name” (Brown has five letters). But it was Thompson’s story that sealed the deal: According to Kable, she told Brayley that “the Apthorps and the Browns were intimate friends. Young William was, therefore, thoroughly acquainted with all of the details of the ‘horrible affair’ and was thus furnished with the ‘material for a strong story.’”

After Thompson came forward, the remaining installments of the book were published under Brown’s name.

7. IT WASN’T BROWN’S ONLY WORK.

In 1789, the year Sympathy was published, Brown also wrote “Harriot, or the Domestic Reconciliation,” which appeared in Massachusetts Magazine (published by Isaiah Thomas). He later penned a play called West Point Preserved (first performed in 1797, three years after Brown died) and some fables and essays. A second novel, Ira and Isabella, was published in 1807 (according to Kable, everything from its misspellings to its plot are very similar to Sympathy, but this novel has a happy ending). More essays and fables were published posthumously. But, according to the forward of the 1969 edition of Sympathy, the book was “the only one of his works to achieve any lasting distinction” [PDF].

Sadly, Sympathy wasn't a great novel. Kable notes that while the book “is the product of a sophisticated reader”—it's littered with literary allusions, from Shakespeare and Swift to Noah Webster and Lord Chesterfield— “… the novel is obviously the work of an unsophisticated writer. In important matters of plotting and characterization as well as in details of diction and grammar, Brown’s clumsiness is all too apparent. ... The ‘thinness of realization’ meant that his finished product fell far short of greatness.”