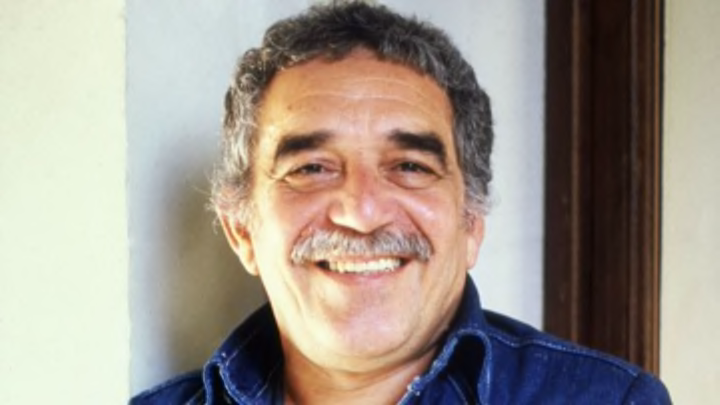

To call Gabriel García Márquez a luminary is an understatement. When he died at 87 in 2014, his native Colombia mandated three days of mourning for the literary superstar popularly known as “Gabo.” Though he wrote many great works, he remains most famous for One Hundred Years of Solitude, which chronicles one unlucky, sometimes incestuous, always memorable family in the fictional village of Macondo. Here are nine fascinating facts about one of literature’s indispensable masterworks.

1. One Hundred Years of Solitude has been a blockbuster since its release.

García Márquez finished writing One Hundred Years of Solitude in late 1966; the book was first released the following year. Since then, it has sold more than 50 million copies in 25 languages, reportedly outselling everything published in Spanish except for the Bible. "If I hadn’t written [the book], I wouldn’t have read it,” García Márquez told the Atlantic in 1973. “I don’t read best sellers.”

2. One Hundred Years of Solitude almost didn't exist.

García Márquez had published four books in Spanish before One Hundred Years of Solitude, but became so discouraged that he gave up writing altogether for more than five years. However, he couldn’t get the idea out of his head. Once he decided to try again, his wife became their family’s sole breadwinner while he threw himself into the work, without any idea where the plot would take him. “I did not stop writing for a single day for 18 straight months, until I finished the book,” he told one interviewer. The manuscript was so large and his family’s savings were so meager that he could only afford to mail one half of it to a potential publisher. By accident, he sent the second half; the publisher was so eager to read the first half, he provided money for the postage.

3. The reception for One Hundred Years of Solitude was a bit like Beatlemania.

Two days after the sometimes-psychedelic One Hundred Years of Solitude debuted, the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band dropped. They each exemplified a similar zeitgeist: García Márquez rocketed to the forefront of a pan-Latin American literary movement called El Boom, which also included heavyweights such as Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa. Everyone from intellectuals to blue-collar laborers to sex workers bought and read and talked about the book. Its appeal across class lines fed into a heady period rocked by political and cultural upheaval. “It was seen as the first book to unify the Spanish-language literary culture, long divided between Spain and Latin America, city and village, colonizers and colonized,” writes Vanity Fair’s Paul Elie.

4. The man who translated One Hundred Years of Solitude deserves his own biographies.

Cuban-American literature professor Gregory Rabassa served as a cryptologist during World War II, breaking codes, visiting the White House, and dancing with Marlene Dietrich. With fluency in at least seven languages, he also interrogated high-level Axis prisoners. On a recommendation from a fellow writer, García Márquez waited a year for Rabassa to become available. When One Hundred Years of Solitude reached the Anglophone world in 1970, he was so happy with the result, he told his translator that the English version was better than his own.

5. 100 Years of Solitude led to a banana company's re-branding.

García Márquez was deeply political his whole life, and also wielded his pen against capitalism. The colonial banana company described in One Hundred Years of Solitude was so clearly modeled on the massive United Fruit corporation, which Márquez had seen ravage his hometown growing up, that the book was part of the reason the company eventually had to rebrand itself—as Chiquita.

6. García Márquez was determined that no one would ever film One Hundred Years of Solitude.

There have been other adaptations of García Márquez's work. Love in the Time of Cholera became a 2017 Hollywood film starring Javier Bardem and Benjamin Bratt. But when the producer Harvey Weinstein approached García Márquez about One Hundred Years of Solitude, there were conditions: "We must film the entire book, but only release one chapter—two minutes long—each year, for 100 years."

7. Magical realism itself was a political act for García Márquez—and for those who followed him.

Dominican-American writer Junot Díaz called magical realism a tool “that enables Caribbean people to see things clearly in their world, a surreal world where there are more dead than living, more erasure and silence than things spoken.” The British-Indian author Salman Rushdie recognized his experience in García Márquez’s Latin America. Ghanaian poet Nii Parkes said the writer “taught the West how to read a reality alternative to their own, which in turn opened the gates for other non-Western writers like myself and other writers from Africa and Asia."

8. By accident, García Márquez stumbled onto another genre: medical realism.

García Márquez had his own conception of magical realism and where it came from, but sometimes what he thought was imagination turned out to be something real. Early in One Hundred Years of Solitude, a plague of insomnia afflicts Macondo. Villagers begin forgetting the words for things and concepts; protagonist José Arcadio Buendía even meticulously labels everyday objects around town. This cognitive impairment was actually described in medical literature for the first time in 1975, eight years after the book’s initial release. It’s called semantic dementia, and García Márquez accurately describes the effects of certain kinds of degeneration in the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes.

9. García Márquez didn’t think the book was all that magical.

What others call magical realism, García Márquez simply calls lived experience. He once claimed that of everything he had written, all of it he’d known, experienced, or heard before he was 8 years old. “You only have to open the newspapers to see that extraordinary things happen to us every day, ” he said in 1988. “There's not a single line in my novels which is not based on reality.”

This list was first published in 2016 and republished in 2019.