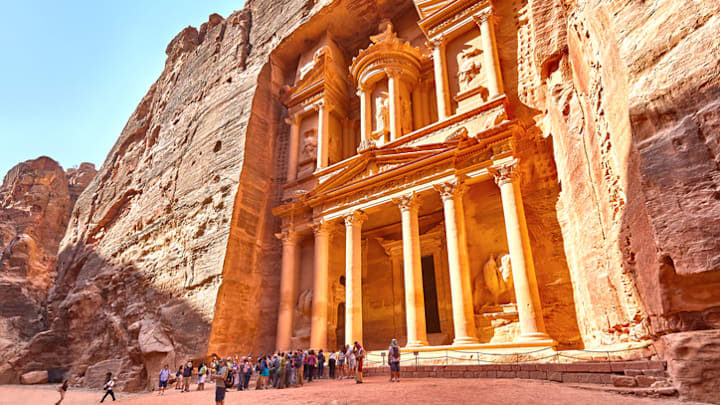

The ancient city of Petra in modern-day Jordan prospered for centuries as a major power along the spice route. The dazzling settlement, with tombs, monuments, and temples carved directly into the rock, has been one of the region’s greatest tourist attractions for decades (and made a memorable cameo in an Indiana Jones movie). Here are a few fascinating facts about the “rose-red city.”

- The Nabataeans built Petra more than 2000 years ago.

- The Romans took over in the 2nd century CE.

- Petra was eventually abandoned.

- The Nabataeans were master stonecarvers.

- Residents built an efficient plumbing system in the desert.

- A biblical story intersects with Petra.

- A Swiss linguist publicized Petra in the early 19th century.

- A British poet immortalized Petra as the “rose-red city.”

- It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Millions voted for Petra as one of the “new” seven wonders of the world.

- Petra was the fictional repository of the holy grail in an Indiana Jones movie.

- Scientists are still unearthing Petra’s history.

The Nabataeans built Petra more than 2000 years ago.

Not much is known about the Nabataeans, who emerged in Arabia in the 4th century BCE. Originally nomads who spoke Arabic and later a form of Aramaic, by 100 BCE they had thwarted attempted conquests by Demetrius I of Macedonia and the Seleucid Kingdom to become a regional power through their dominance of trade routes between coastal cities and interior settlements. Though they occupied various areas of southern Jordan, Arabia, and the Naqab (or Negev) Desert, the Nabataeans made Petra, surrounded by sandstone mountains and cliffs, their capital city.

The Romans took over in the 2nd century CE.

It is unclear exactly when the Nabataeans built Petra, but by the 1st century BCE, traces of Hellenistic and Roman influence could be seen in its art and architecture, including statues of Nike, a Roman-style theater carved into a mountainside that could seat thousands, and paved streets. Various Nabataean rulers, such as Aretas III and Aretas IV, formed alliances and paid tributes with Rome that shaped the next few centuries, but upon the death of Rabbel II, the last Nabataean king, the city finally came under complete Roman control in 106 CE.

Petra was eventually abandoned.

At the height of the city’s power, 20,000 to 30,000 people lived and worked in Petra. But the Romans altered the Nabataean trade routes, diverting them away from Petra and favoring sea-based travel around the Arabian peninsula. (Even earlier, Rabbel II himself likely moved the capital from Petra to Bostra—modern-day Bosra in Syria—around 93 CE.) A major earthquake in 363 CE destroyed many buildings and homes and decimated the city’s vital water system. As their power waned and another earthquake struck, the Nabataeans ultimately left the city, taking most of their treasures and possessions with them. Outposts built during the Crusades are the last pieces of evidence that the West knew of Petra for half a millennium.

The Nabataeans were master stonecarvers.

Petra takes its name from the Greek πέτρα (pétra), which means “stone.” And the Nabataeans proved to be especially adept at carving intricate buildings and artwork in their sandstone surroundings. About 3000 homes, temples, tombs, banquet halls, and other dwellings have been documented in Petra, all carved by hand with pickaxes and chisels and built with the support of scaffolding and platforms. Masons typically used a top-down method to work their way down 100-foot cliffs, or sometimes chipped out holes, inserted a piece of wood, and added water to make it swell and crack the rock face.

Residents built an efficient plumbing system in the desert.

Along with their talents as traders and stonemasons, the Nabataeans were equally as skilled at channeling clean water to support the city’s population. The surrounding desert provided just 6 inches of rainfall per year, but a collection of local springs, diverted through terracotta pipes and into cisterns, pumped in up to 12 million gallons of fresh water per day. The city also boasted a large dam that protected the city from floods, and directed the water into a channel called the “dark tunnel.” Many Bedu tribes living in the area still use this ancient water-collecting system.

A biblical story intersects with Petra.

Atop a 4430-foot mountain known as Jabal Haroun sits a white-domed mosque built sometime in the 14th century. The mountain is also called Mount Aaron, and the mosque is a tomb to Aaron, a prophet and brother of Moses. Aaron is allegedly buried in the area, and the surrounding valley, called the Valley of Moses, is supposedly where Moses struck a rock and brought forth water, described in the Book of Numbers.

A Swiss linguist publicized Petra in the early 19th century.

Born in 1784, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt traveled extensively throughout the Middle East and Egypt after studying at Cambridge University. While traveling from Syria to Egypt, Burckhardt visited Petra and became the first outsider to see the city, previously unknown to Europeans and unmapped, in 500 years. (Local people, on the other hand, often spent the winter months in its caves.) He published a book in 1822 called Travels in Syria and the Holy Land that described the city, and several thousand Westerners visited the site over the next century, including American painter Frederic Edwin Church and English artist Edward Lear.

A British poet immortalized Petra as the “rose-red city.”

In 1845, a student named John William Burgon won Oxford University’s Newdigate Prize for his poem “Petra.” Though he had never ventured to the region, his descriptions of the city as “rosy-red—as if the blush of dawn” and “a rose-red city—half as old as time” have remained some of the defining descriptors of Petra.

It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1985, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) designated Petra a World Heritage Site. The organization continues to work with Bedu (a.k.a. Bedouin) tribes to ensure the increased demands of tourism and modernization do not damage its cultural heritage and sublime beauty.

Millions voted for Petra as one of the “new” seven wonders of the world.

The NewSevenWonders project, led by Swiss filmmaker Bernard Weber from 2000-2007, encouraged internet users to vote for a new crop of the world’s favorite monuments. The unscientific poll, supported by the United Nations but not UNESCO (and which some dismissed as a publicity stunt) reeled in 100 million votes worldwide. Along with the Great Wall of China, the Colosseum in Rome, Mexico’s Chichen Itza, Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro, Peru’s Machu Picchu, and India's Taj Mahal, Petra was named one of the winners during a star-studded event in Lisbon, Portugal.

Petra was the fictional repository of the holy grail in an Indiana Jones movie.

Before the release of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade in 1989, just a few thousand tourists visited Petra annually. The filmmakers used the Siq (a sandstone canyon) and Al Khazna (the treasury) as locations for the fictional home of the holy grail. Soon Petra was known worldwide, and it became Jordan’s most popular tourist destination, with thousands of people a day trekking to the desert locale after the film's release.

Scientists are still unearthing Petra’s history.

Using Google Earth, drones, and the satellite imagery, archaeologists Sarah Parcak and Christopher Tuttle studied Petra and the surrounding area and discovered the outlines of a previously unknown monument not far from the city center. Parcak and Tuttle described the structure in 2016 as an open platform roughly the length and twice the width of an Olympic swimming pool with a slightly smaller platform, columns, a small building, and a large staircase. The structure is believed to have been used for public ceremonies and was likely built by the Nabataeans during the middle of the 2nd century BCE.

Discover More Amazing Stories of Archaeology:

A version of this story was published in 2016; it has been updated for 2024.