Our definition of fun is constantly changing. In one century, collecting ferns may be the hobby of choice, while in the next people prefer binge-watching cat videos. But no matter what cultural trends are gripping the globe, one form of entertainment always persists.

Board games originated in ancient Egypt, and in today’s digital age they’re as popular as ever. In It's All a Game, out now, author Tristan Donovan traces the history of board games from chess to Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. We’ve pulled some of the most fascinating origin stories from the book for a look at how seven iconic games came to be.

1. MONOPOLY

Many modern players see Monopoly as a glorification of cutthroat capitalism. It was banned in communist China and the Soviet Union, and following his rise to power in Cuba, Fidel Castro accused it of being “symbolic of an imperialistic and capitalistic system.” But the game’s creator intended it to convey something much different.

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie was a vocal supporter of the single tax movement during the late 19th century. The proposition called for the abolishment of all taxes in favor of one tax placed on property. By relying on citizens who owned land for tax revenue, the policy would have hopefully narrowed the gap between wealthy landlords and their working-class tenants.

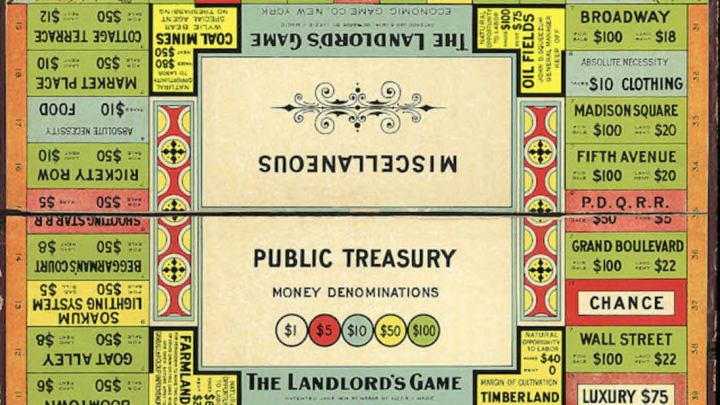

To make these principles as engaging as possible, Lizzie Magie turned them into a board game in 1902. The object of The Landlord’s Game, as it was initially called, was to snatch up as much land as possible. As available properties on the board grew scarce and rent rose higher, the landlords would watch their fortunes multiply while the other players descended into bankruptcy. The winner was the remaining land baron who ended up owning everything in play.

Magie thought the game’s critique of greedy landlords was obvious, but it eventually evolved into a beast far removed from her original creation. After patenting it in 1904, she sent the game to Parker Brothers, where it was rejected for being too political. Nonetheless, the game attracted a small base of fans. Soon people were revising and improving upon the game with handmade versions of their own. One of these new versions, now called Monopoly, found its way back to Parker Brothers in 1934. This time they bit. But before they could publish the game, they had to take care of Magie’s original patent. She agreed to sell them the game for $500 under the condition that copies of her original Landlord’s Game would also be released. It was painfully clear which game consumers preferred; sales of the glitzy, money-grubbing Monopoly soared while Magie’s cardboard political parable lay dead on the shelves.

2. LIFE

By modern board game standards, it doesn’t get much simpler than Life. But the game revolutionized the medium when it was produced by a young Milton Bradley in 1860. Growing up in devout Protestant New England in the 19th century, Bradley had been taught that games were a sinful distraction. At age 23, he attempted to reconcile this cultural belief with his desire to design a board game. The result was The Checkered Game of Life—a lecture on morality presented as a sheet of cardboard. To play, participants lost and collected points by progressing through the stages of life represented on the white squares. Some squares were positive (like Honesty, Perseverance, and Industry) while vice spaces (like the not-so-family-friendly Suicide square) were less desirable. To move across the board, players spun a numbered “teetotum” as dice were still associated with the illicit act of gambling. The first player to reach 100 points was rewarded with the gift of “Happy Old Age.”

Even with its heavy-handed message, Bradley feared his game would be rejected by puritanical audiences in New England. He took his product to New York City instead, and his instincts were proven correct; he sold all of the several hundred copies he brought with him in a matter of days. The Checkered Game of Life would go on to sell 40,000 copies in its first year. After falling into obscurity at the end of the century, it was resurrected as the more secular Game of Life by the Milton Bradley Company in 1959.

3. CLUE

In the early 20th century, Great Britain was captivated by crime stories. One of the most enduring pieces of pop culture to come out of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction wasn’t a novel, but rather a board game designed by British husband-and-wife team Anthony and Elva Pratt. According to It's All a Game, their game centered around the same type of rural country houses that served as the settings for so many murder mysteries of the day.

After revising some unsavory elements (the original name of "Murder" was changed to Cluedo; the gun room was replaced with an extension of the dining room), the UK publisher Waddingtons bought the rights in 1945. Getting the game produced overseas proved to be more challenging. Though Parker Brothers president Robert Barton enjoyed Cluedo, he refused to release it based on a long-standing company rule that prohibited any products related to murder. But the game stuck with Barton. He eventually convinced the founder of Parker Brothers to make an exception to his murder rule, and the brand released Cluedo in the U.S. under the name Clue in 1949.

4. OPERATION

Toy designer Marvin Glass was the man responsible for bringing board games into the plastic age. He shook up the industry with Mouse Trap in 1963, then again with Operation two years later. But before Glass got his hands on it, the game was concocted by an industrial design student at the University of Illinois.

For a class project, John Spinello constructed a metal box outfitted with a series of holes along a winding groove through which users had to guide a metal probe. If the tool touched the sides of the path, a buzzer would sound. Spinello arranged a meeting with Marvin Glass through his godfather, a model maker at Glass's game company, to pitch him the concept. Glass bought the invention and transformed it into Operation—a game that had players carefully lift plastic items like spare ribs and stomach butterflies out of a cartoon surgical patient. The object was to remove all the loose bits without hitting the metal edges of the openings with the toy tweezers. Operation was an instant success for Glass and his company. Spinello, meanwhile, came away with nothing but a $500 check and the empty promise of a post-graduation job that never came to fruition.

5. TWISTER

If Twister had been released a decade earlier, it may have never become a household name. But the game hit shelves in the mid-1960s, right as the sexual revolution was starting to buck the uptight ideals of the previous generation.

A design agency co-owner named Reyn Guyer thought up the idea as a promotional item for one of his clients. If customers sent in enough proofs of purchase to the company, they would receive a "free" gift in return. Guyer whipped up a prototype of a full-body game, dubbed "King’s Footsie," on a sheet of fiberboard to see if it would work as a possible prize. He decided it had potential, but not as reward for a mail-in promotion. Instead, he started shopping the concept around to game publishers. By the time he pitched it to Milton Bradley, it had been renamed “Pretzel” and now involved players planting their hands on a mat in addition to their feet.

After negotiating a name change to Twister, the company agreed to make it—a risk that almost didn’t pay off. Retailers were reluctant to stock it. A game that involved the mingling of coed limbs on the floor didn’t flow with the family-friendly vibe many stores were trying to project at the time. Milton Bradley was about to pull the plug on Twister for good when an appearance on The Tonight Show rewrote the game’s history. On May 3, 1966, millions of viewers watched as Carson and his guest Eva Gabor tested out the new game on live television. Sales skyrocketed immediately. The game wasn’t without its scandalized critics, but increasingly liberal attitudes towards sex secured Twister's place on the shelf for decades to follow.

6. TRIVIAL PURSUIT

Prior to the release of Trivial Pursuit, board games carried a bit of a stigma. A handful of titles like chess, backgammon, and Scrabble were acceptable for adults to play, but for the most part a board game wasn’t something you broke out over drinks. As Donovan explains in It's All a Game, a photo editor and a sports journalist from Montreal changed that in the early 1980s. After realizing there was nothing on the market like it, friends Chris Haney and Scott Abbott put together a prototype of a game that quizzed mature players on subjects like art, sports, history, and entertainment. They scoured trivia books to fill out cards with questions like “What is the first flavor in Life Savers candy?” and “How long did Yuri Gagarin spend in space?” The team attracted enough investors to publish the game independently, but even then convincing stores to stock an expensive and old-fashioned-looking board game at the height of Atari mania was a tough job. Not many retailers took a chance on Trivial Pursuit, but those that did watched it fly off the shelves. Soon stores were reordering the game, and it aroused enough attention that the board game producer Selchow and Righter bought the rights in 1983. Trivial Pursuit sold 20 million copies in its first year, proving that board gaming could be a fashionable hobby for older consumers.

7. SETTLERS OF CATAN

Klaus Teuber found success as a board game designer prior to making Settlers of Catan. He’d already won the Spiel des Jahres award, the highest honor in the board game world, three times in his career. But sales were never impressive enough for him to quit his full-time job as a dental technician in Germany. With Catan, he struck upon something huge. The theme of the game was inspired by Teuber’s own fascination with Viking history. He tested various iterations on his family for four years before finally settling on the board of hexagon-tiled spaces players know today. Unlike his previous titles, the initial buzz surrounding Settlers of Catan didn’t fade away following its German release in 1995. The hype only grew stronger until the game migrated overseas, paving the way for the German-style board game trend. The game was the Monopoly antidote U.S. markets desperately needed; the rules were simple, all the players were kept engaged throughout, and a whole game could be completed in about an hour. Catan was hardly the first German board game to offer these qualities, but it was first to introduce that style of gaming to a global audience.

Hungry for more board game history? You can buy It's All a Game here.