Recently, an item from the collection of London’s famous Victoria and Albert Museum caused something of a stir online when the museum’s metalwork curator unboxed a rare antimonial cup dating back to the 17th century.

As its name suggests, the cup is made of the toxic metal antimony, and was part of a voguish medical cure much in use at the time. A small amount of wine would be poured into the cup and left to stand overnight, during which time just enough of the toxic antimony would dissolve into the liquid for the wine to work as a mild purgative when drunk the following day.

This, it was believed, could be used to rebalance the body’s four humors—yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood—imbalances of which were long considered to cause illness.

The V&A’s toxic cup isn’t the only bizarrely dangerous practice from the medical textbooks of yesteryear, however. Long before the days of modern medicine and our modern understanding of what makes us unwell, physicians often prescribed all manner of unusually perilous treatments.

Mercury Therapy

Much like the antimonial cup, preparations of mercury have likewise long been used to treat all manner of diseases and conditions, as the highly poisonous liquid metal worked as a purgative that doctors believed could rid the body of ills through sweating, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Leprosy and even syphilis were among the many conditions various mercury therapies were prescribed for, with the precise methods and quantities of the mercury administered to the patient depending on the scale of the infection, and, more often than not, their bank balance.

At the simpler end of the scale, patients might merely be encouraged to use lotions or consume pills containing a small quantity of mercury; at the more drastic end, they might be placed in fumigation chambers to inhale mercury vapors, or even have preparations of the liquid metal administered via a douche or even an enema.

Trepanning

Taking its name from a Greek word meaning to bore a hole, trepanning is an age-old medical technique in which a hole is directly made into a patient’s skull. One of the oldest (if not the oldest) surgical techniques in human history, evidence of trepanning dates back more than 7,000 years, during which time it appears to have been used for all manner of conditions from relieving pain to healing injuries, and even madness and other mental illnesses.

The trepanning method itself changed somewhat over time, too, with early evidence suggesting our prehistoric ancestors scraped, rather than bored, a pain-relieving skull hole; by the time of the Ancient Greeks, more specific tools known as trephines had been designed, which could be used more easily and swiftly to remove a perfect circle of cranial bone.

Trepanning continued to be used to alleviate various cranial and psychological problems right up until the 19th century (often without anesthesia or adequate sanitation, giving this already dangerous technique a high post-surgery infection rate, too).

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, it gave way to the modern craniotomy—a far more controlled neurosurgical procedure in which cranial bone is removed for, for instance, biopsy or further examination. Ultimately, although the surgical offspring of this most ancient technique remains a common medical procedure today, trepanning itself has long been considered an antiquated practice.

Corpse Medicine

Hapless medical patients have been advised by physicians to either consume or otherwise somehow administer all kinds of distasteful and downright dangerous substances over the centuries, ranging from both human and animal excrement in the ancient world (variously used as a topical contraceptive in Ancient Egypt and a cure for cataracts in Ancient Rome) to enemas of blown tobacco smoke (administered to patients suffering from cholera as relatively recently as the 18th century).

Surely among the most repulsive medicines ever concocted throughout history, however, is the so-called “corpse medicine.”

Also known as medical cannibalism, corpse medicine (as its name suggests) involves the consumption of various parts of dead human bodies in a vain attempt to cure or alleviate some illness. It has been suggested that this ancient practice might have first emerged from the equally ancient theory of sympathetic medicine, in which like was believed to cure like; blood would be drunk to cure bleeding, for instance, while ground-up skulls could be consumed to cure headaches, and the Romans reportedly used a “liquor of hair” to cure baldness.

But all manner of medicines prepared from dead bodies have been recorded over the centuries, not all of which follow this “sympathetic” template. The Romans, for instance, also used hair to cure jaundice, while in ancient Europe, the fat from the corpse of a hanged man, known as hangman’s grease, was used as a cure for arthritis.

Even King Charles II of England is known to have prepared his own supposed cure-all, regularly taking sips from a tincture of ground skull mixed with alcohol known as the “king’s drops,” while the vogue for all things Egyptian that structured Victorian England led to a resurgence of interest in the ancient consumption of ground mummies as medicine.

Needless to say, of course, corpses aren’t the most hygienic of items at the best of times. As a result, this bizarre practice not only risked poisoning the patient (“It causes great pain in their stomachs … and brings about serious vomiting,” the French surgeon Ambroise Paré wrote of consuming mummies in the 1500s) but also exposed the luckless preparer of the medicine to all manner of infections and disease.

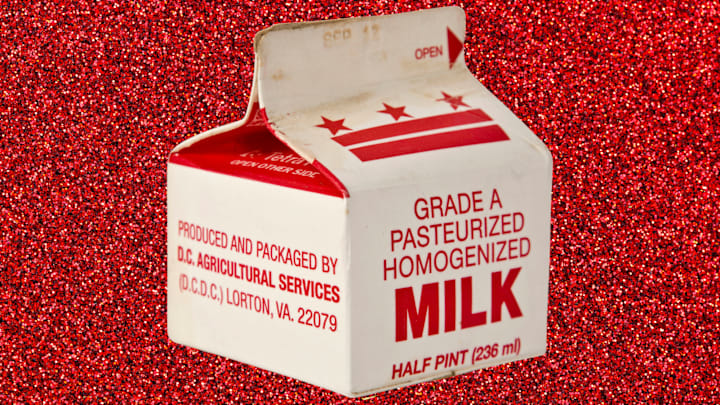

Milk Transfusions

Before ABO blood types were discovered and first described in 1901 (winning the Vienna-born physician Karl Landsteiner the Nobel Prize for Medicine), blood transfusions were a perilous business.

Administering the wrong type of blood to a patient could easily cause more harm than good, and adverse reactions to blood transfusions were common. In fact, deaths caused by incompatible blood types clotting in the infused patient became so frequent and high-profile in the 1600s and 1700s that the procedures were condemned, and research into the topic remained dormant for more than 150 years. Finally, in 1854, a pair of Canadian physicians named James Bovell and Edwin Hodder came up with a remarkable idea: substituting problematic blood with seemingly far less problematic milk.

The milk, the doctors believed, would simply be absorbed into the patient’s existing blood and eventually be transformed into “white corpuscles” (what we would now call white blood cells). Remarkably, their first patient—a 40-year-old gentleman in Toronto—survived after he was administered 12 fluid ounces of cow’s milk. The next five, however, did not.

Research into milk transfusions continued for the next two decades, with understandably similar results; after the deaths of several more patients amid similar trials, the practice was quietly retired in 1880.

Morphine Syrup

In the late 1840s, a lady named Charlotte Winslow, in Bangor, Maine, developed a new patent medicine that she marketed as “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.” Widely advertised on both sides of the Atlantic in newspapers and on posters showing pictures of gently smiling and sleeping babies and children, the syrup was marketed as “the mother’s friend for children teething,” and claimed to be able to soothe “any human or animal.”

The medicine, Mrs. Winslow’s advertisements claimed, “soothes the child, softens the gums, allays all pain, cures wind colic, and is the best remedy for diarrhoea.” It proved a staggeringly popular development, and by the 1860s, more than 1.5 million bottles of Mrs. Winslow’s syrup were being sold every year.

By the early 1900s, however, the true effects of Mrs. Winslow’s medicine were slowly becoming clear. Just one teaspoonful of her syrup, it was later revealed, contained the same amount of morphine as 20 drops of opium tincture laudanum; a safe dose of laudanum for a baby, it was recommended at the time, was no more than 2–3 drops.

As a result, a single dose of the medicine contained a potentially lethal dose of morphine; because it took decades to link the syrup to the sudden prevalence of childhood deaths, it is unclear precisely how many children died as a result of taking Mrs. Winslow’s morphine syrup, but it is likely to number in the thousands. The resulting public outcry over the deaths eventually led to the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, which required the precise ingredients of all products to be listed on their packaging for the first time.