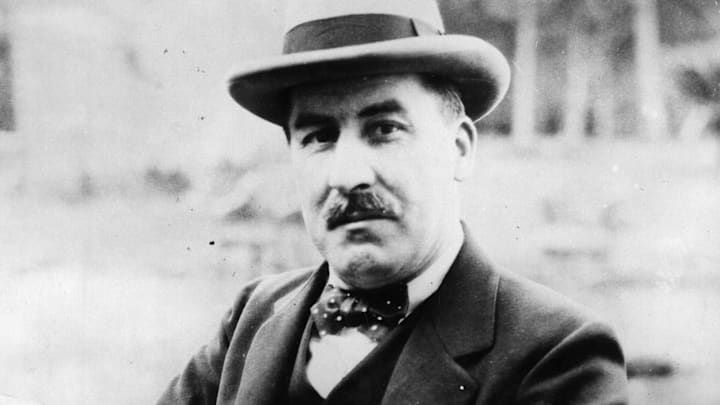

It’s been a century since archaeologist Howard Carter (born in Norfolk, England, on May 9, 1874) and his team discovered the tomb of an obscure Egyptian pharaoh named Tutankhamen, kicking off a period of Egyptomania and a fascination with the pharaoh that endures to this day. In honor of the anniversary of Carter’s most famous discovery, let’s do a little excavation on his life.

1. Howard Carter was the son of a famous illustrator.

Samuel John Carter was an artist who drew and painted animals for the Illustrated London News; he also accepted private commissions and had his work featured regularly in exhibitions at the Royal Academy of Art. Samuel taught his artistic skills to his youngest child, which helped pave the way for Howard’s eventual career in archaeology.

2. Carter first went to Egypt as an artist.

Through his parents’ connections, Carter found his way to the home of Lady Mary Amherst, a wealthy philanthropist and amateur Egyptologist with a huge collection of artifacts. Lady Amherst was so impressed with Carter’s sketches of her antiquities that in the early 1890s—when he was still a teen—she sponsored him on a trip to Egypt. There, he worked with archeologist Perry Newberry and then Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (now considered the father of modern archaeology), putting his skills as an artist to use by drawing sculptures and inscriptions found in tombs and temples.

3. Tut's wasn’t the only famous tomb he worked on.

By 1903, Carter was supervising excavations in the Valley of the Kings that uncovered the tombs of Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut (ruled circa 1473–58 BCE) and Thutmose IV (ruled 1400–1390 BCE), although neither contained their actual mummies. There’s some evidence, however, to suggest that one of the mummies Carter found in a chamber called KV60 in 1903 was Queen Hatshepsut, making his royal tally quite impressive indeed.

4. An incident known as the Saqqara Affair nearly ruined his career.

According to Petrie, who wrote about the 1904 incident in his memoir, his wife was working at the Saqqara Necropolis in Giza and had several other women visiting her hut when “some drunken Frenchmen” tried to force their way in. They were stopped by a “cook boy,” but then went to what Petrie called the “official house” and picked a fight with local guards, smashing some furniture for good measure. Other accounts say the Frenchmen demanded to see tombs, forced their way in, then smashed things and caused a ruckus when they were denied candles.

Whatever happened, Carter, who was then the chief inspector of antiquities in the area, told his local guards to defend themselves against the intruders—an unthinkable thing to do to wealthy Europeans. The French consul requested an apology for this seemingly normal reaction; Carter refused. The consul demanded his resignation—and got it. Carter was without a job for three years. To make a living, he sold watercolors to tourists.

5. Carter didn’t find Tut’s tomb overnight.

Carter’s period of unemployment ended when he received a commission from George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, to excavate Egyptian antiquities in 1907—the beginning of a long and lucrative partnership.

It was widely thought that the Valley of the Kings was tapped out by the 1910s, but Carter was convinced that there was at least one undiscovered tomb left there, thanks to pottery shards found in 1909 that were inscribed with the word Tut.ankh.amen—and despite the fact that many believed a tomb unearthed in late 1908 (KV58) was Tut’s.

Carnarvon received permission to excavate in the Valley of the Kings in 1914, and in 1917, Carter began the search for the king he believed was still at large. But after five years of methodical excavations—during which Carter and his team, according to Toby Wilkinson in A World Beneath the Sands, “clear[ed] the [unexcavated] section of the valley all the way down to the bedrock,” ultimately moving up to 200,000 tons of earth—Tut was still MIA. In 1922, Carnarvon warned Carter that he had just one more year to find something or have his funding pulled. The concealed staircase to Tut’s tomb was discovered just a few days later.

6. He didn’t believe in King Tut’s curse.

The legend around the “mummy’s curse” is almost as famous as Tut himself. Many people who were present at the opening of Tut’s tomb or were somehow tied to the team ended up dying early deaths or suffering horrible tragedies. The curse gained worldwide recognition when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author behind Sherlock Holmes, proclaimed that the team was cursed by “elementals—not souls, not spirits—created by Tutankhamun’s priests to guard the tomb.” Carter, however, did not believe in the curse. In fact, the idea irritated him so much that he called any speculation about it “tommy rot.”

7. His Tut work was never finished.

Carter and his team worked for a decade to excavate and catalog the artifacts from Tut’s tomb—but even then, Carter’s work with the boy king wasn’t finished. He traveled Europe and North America giving lectures about Tut, and even met with President Calvin Coolidge to discuss his work in 1924. (The Coolidges requested that Carter deliver a private lecture to them and some guests following that meeting, but as T.G.H. James writes in Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun, they were ultimately not able to attend due to a family emergency.) Carter also wrote extensively on the subject, publishing The Tomb of Tutankhamen just a year after its discovery. He was working on a more scientific account of his findings as well, but was unable to finish the work before he died.

8. Carter’s epitaph was fitting.

Carter died of cancer in 1939 when he was just 65 years old. The inscription on his tomb bears the same words found on what he called the Wishing Cup of Tutankahmen, an artifact found in the tomb: “May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness.”