Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 278th installment in the series.

June 7-14, 1917: Battle of Messines

The abject failure of the Nivelle Offensive in April 1917 triggered mutinies throughout the French Army in May and June, threatening to paralyze the Allied war effort. Although the Germans never caught wind of them, the Allies were understandably worried they might try to exploit the disastrous French defeat and ensuing chaos with a sudden onslaught against the demoralized, disorganized French forces.

At the same time huge shipping losses inflicted by U-boats beginning in the spring of 1917 focused Allied attention on German submarine bases on the coast of Belgium, whose location allowed the U-boats to slip through the English Channel to prey upon the Atlantic sea lanes (as opposed to the much longer route through the North Sea and around Scotland, which burned up precious fuel, limiting their time in the hunting grounds). The Royal Navy made a number of attempts to destroy or disable these bases, including an attack by destroyers against Ostend on June 4-5, 1917, but these were ultimately unsuccessful, while other measures – including mine fields and submarine nets to block the Channel route – were still mostly ineffective at this stage of the war.

To relieve pressure on the French, deprive the Germans of their submarine bases, and maybe even achieve a strategic breakthrough, Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, planned to carry out two linked offensives in Belgium in the summer of 1917. The first attack yielded a British tactical victory at Messines; the second, the waking nightmare of Passchendaele.

"THE NOISE WAS IMPOSSIBLE"

The first offensive concentrated on high ground south of Ypres (already the scene of two ferocious battles in 1914 and 1915) and especially the Messines Ridge near the village of the same name – strategic positions with a sweeping view of enemy lines, laying the groundwork for the second offensive east of Ypres.

At Messines, twelve divisions of the British Second Army under Sir Herbert Plumer, numbering 216,000 men (including Canadian and ANZAC troops) would face five divisions of heavily entrenched defenders from the German Fourth Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, numbering 126,000 men – not a favorable balance of forces for the attackers, by the standards of the First World War.

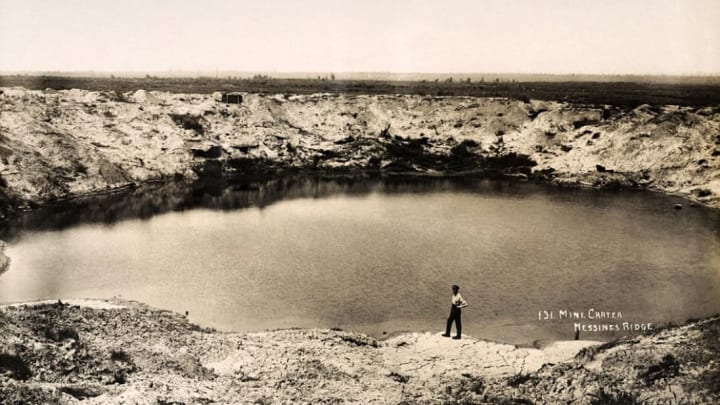

However the British had a few key advantages, including the new tactic of the creeping barrage, which had proven effective at the recent Battle of Arras, and another weapon of truly demonic power – a chain of 26 massive mines, painstakingly excavated beneath the German lines on Messines Ridge over many months and then packed with over 450 tons of ammonal high explosive. The detonation of these mines would produce one of the largest manmade non-nuclear explosions in history (although four of the mines failed to explode; top, one of the craters).

The British offensive was preceded by ten days of extraordinarily intense artillery bombardment, as over 2,200 guns of varying sizes dumped approximately 3.5 million shells on the German lines. Finally, around 2:40 a.m. on June 7, 1917 the guns briefly fell silent, while the first wave of British soldiers quietly crept out of the trenches and lay flat on the earth in no-man’s-land, preparing to rush the German lines as soon as the mines exploded (below, British soldiers take communion during the battle).

The sudden pause in firing alerted the Germans that the British infantry attack was imminent, and the defenders streamed back to their frontline trenches in preparation for the assault – exactly as the British has hoped they would. At 3:10 a.m. the mines were fired and the bowels of the earth opened, while simultaneously the British guns resumed firing. Lieutenant A.G. May, a British machine gun officer, recalled the moment:

When I heard the first deep rumble I turned to the men and shouted, “Come on, let’s go.” A fraction of a second later a terrific roar and the whole earth seemed to rock and sway. The concussion was terrible, several of the men and myself being blown down violently. It seemed to be several minutes before the earth stood still again though it may not really have been more than a few seconds. Flames rose to a great height – silhouetted against the flame I saw huge blocks of earth that seemed to be as big as houses falling back to the ground. Small chunks and dirt fell all around. I saw a man flung out from behind a huge block of debris silhouetted against the sheet of flame… At the same time the mines went off the artillery let loose, the heaviest group artillery firing ever known. The noise was impossible and it is impossible for anyone who was not there to imagine what it was like.

According to later estimates around 10,000 German soldiers lost their lives in the space of a few moments when the mines exploded. Another British officer, E.N. Gladden, recorded similar impressions of the horrific event:

The ground began to rock and I felt my body carried up and down as by the waves of the sea. In front the earth opened and a large black mass was carried to the sky on pillars of fire, and there seemed to remain suspended for some seconds while the awful red glare lit up the surrounding desolation. No sound came. I had been expecting a noise from the mine so tremendous as to be unbearable. For a brief space all was silent, as though we had been too close to hear and the sound had leapt over us like some immense wave… And then there was a tremendous roar and a tearing across the skies above us, as the barrage commenced with unerring accuracy. It was as though a door had been suddenly flung open. The skies behind our lines were lit by the flashes of many thousand guns, and above the booming din of the artillery came the rasping rattle of the Vickers guns pouring a continuous stream of lead over into the enemy’s lines.

As so often, some observers noted that the horror and violence of the war were accompanied by surreal, spectacular beauty (above, the “Pool of Peace,” a pond formed in one of the craters). Jack Martin, a signaler in the Royal Engineers, wrote in his diary:

For several minutes the earth rocked to and fro oscillating quite twelve inches. It was an experience which I shall remember very vividly for the rest of my life – all the phases of the preliminary bombardment, the calm silence that succeeded them suddenly broken by a most terrific uproar, the weird sights of moving men and things in the semi-darkness, the rolling clouds of smoke picked out every now and then with shooting tongues of flame, all formed a tremendously wonderful sight. It was stupendous beyond the imagination.

Private Edward Lynch, an Australian soldier, left a description of strange high-altitude atmospheric effects later associated with the explosion of nuclear weapons:

‘Look!’ And there to the north on the crown of the great black dome we know is Messines Hill, we see a movement as of an enormous black tin hat slowly rising out of the hill. Suddenly the great rising mass is shattered into a black cloud of whirling dust as a huge rosette of flame bursts from it and great flames lick, dancing and flickering. High up in the sky above the explosion we see a bank of dark clouds turn red from the reflection of the terrible burst below.

With debris still raining down, and the creeping barrage forcing any remaining defenders to take cover, the attackers began to advance across no man’s land along a stretch of front ten miles long in the slowly rising dawn, supported by tanks and a large number of reserve troops waiting to exploit the breakthrough. Unsurprisingly, following the detonation of the mines in many places the advancing troops found that there was no resistance – and in fact no sign of defenders, trenches, or fortifications of any kind, aside from small scraps of barbed wire. In other places hundreds of German soldiers, still alive but traumatized by the explosions, surrendered en masse.

After around half an hour the attackers had captured their first objective and advanced halfway to the German second line. But plenty of German defenders remained alive, putting up a fierce fight from isolated strongpoints, while others withdrew to their rear trenches on the far slope of the ridge, where they worked feverishly to establish new defensive positions. Meanwhile German artillery, some of which managed to survive the mines and bombardment, plastered the attackers with shrapnel, high explosives, and poison gas. Lynch, the Australian private, described British artillery in action around 11 am, along with the German counter-barrage:

We watch the gunlayer on the nearest gun. He sits on his job laying his gun just as fast as the men can feed and fire it. His body jerks to the kicking recall. Blood is streaming from his nose and ears but he never lets up – bleeding from concussion. The great tanks move towards the big Messines Ridge. We move off to climb that great dusty, smoking hill… Suddenly the hillside above kicks up in fifty places as the Fritz barrage of screeching, roaring, bursting shells comes down and through which we must somehow walk… We see a section of men get a shell clean amongst them and get tossed like ninepins everywhere. One lone man rises and moves on where eight moved only a minute before.

The German guns also hit British rear areas in an attempt to disrupt British artillery and block the arrival of fresh troops. William Presser, a bombardier in the Royal Artillery, recalled being gassed at Messines while trying to sleep in a dugout later in the battle:

I was awakened by a terrific crash. The roof came down on my chest and legs and I couldn’t move anything but my head. I thought, “So this is it, then.” I found I could hardly breathe. Then I heard voices. Other fellows with gas helmets on, looking very frightening in the half-light, were lifting timber off me and one was forcing a gas helmet on me… The next thing I knew I was being carried on a stretcher past our officers and some distance from the guns… I supposed I resembled a kind of fish with my mouth open gasping for air. It seemed as if my lungs were gradually shutting up and my heart pounded away in my ears like the beat of a drum. On looking at the chap next to me I felt sick, for green stuff was oozing from the side of his mouth… I was always surprised when I found myself awake, for I felt sure that I would die in my sleep.

Tragically the British also suffered a number of casualties from “friendly fire,” due to confusion about the position of troops. James Rawlinson, a Canadian engineer, recalled surviving a German bombardment only to be hit by a British shell, permanently losing his sight to a sliver of shrapnel:

The enemy guns… opened up with a terrific fire, and the scenery round about was soon in a fine mess. Shells of varying calibre came thundering in our direction, throwing up, as they burst, miniature volcanoes and filling the air with dust and mud and smoke… We were congratulating ourselves that we were to pass through this ordeal uninjured, when suddenly a 5.9-inch shell fell short. It exploded almost in our midst, and I was unlucky enough to get in the way of one of the shrapnel bullets. I felt a slight sting in my right temple as though pricked by a red-hot needle--and then the world became black.

Meanwhile the attackers pressed on over Messines Ridge, with Lynch recalling:

Dust and smoke cover everything. We can barely see the sections on either hand yet somehow they still climb on and so do we. Eyes stinging from gas, dust and smoke, our dry throats burning from the biting fumes of the shells, coated with sweat and dirt, we climb through this terrible barrage, walking on the crumbling edge of a roaring, flashing volcano. Fifty times we’re up and down as shells nearly get us. Mad with thirst we move ever on. The leading two men of our little section go down hit. We step by them and climb on as orders are that no man is to fall out to attend the wounded.

German defenders captured during the attack could count themselves lucky, as according to Lynch, the attackers often weren’t in the mood to take prisoners alive:

‘Kamerad! Kamerad!’ And a small bunch of Fritz rush out of the pillbox as we near it. ‘Kamerad this amongst yourselves!’ And Whang! one of our men has thrown a bomb at them. Terrified, they fly out of the trench. Crack! Crack! Crack! blaze our rifles and not an enemy is on his feet. They’ve gone the way most machine-gunners go who leave their surrender too late. War is war.

Despite sustaining heavy casualties in some places, by the afternoon of June 7 the attackers had captured their final objective, the German third defensive line behind Messines Ridge. However the battle continued to rage, as the British pushed forward and the Germans staged a fighting retreat, while Rupprecht rushed reinforcements up to stem the advance (below, a captured trench). During the following week the British made their biggest gains on the southern half of the battlefield, allowing them to consolidate control of the lower reaches of the Messines Ridge to the south, while forcing the Germans back towards the village of Warneton.

Of course these gains came at a heavy price, as the German defenders dug in and more reinforcements arrived. Lynch recalled his final memory of the battle after being wounded on June 10:

I must reach our trench. I begin to crawl up the side of the shell hole I’m in. The side of the hole keeps moving upwards. Struggle as I may I can’t get out, can’t climb that moving bank. I begin to slip back, back, back into the hole and the bottom has dropped out of it. I can’t climb, can’t cling to the moving sides of this bottomless hole, and begin to drop, drop, drop into swaying utter blackness.

By June 14 the attackers had advanced up to three kilometers in many places – a major victory in the context of trench warfare. But as so often during the war, victory was as ghastly as defeat, although soldiers found themselves increasingly inured to scenes of horror. Martin, the signaler in the Royal Engineers, described advancing over the captured ground in his diary on June 8, 1917:

We had seen numerous dead bodies in all the ghastly horrors and mutilations of violent death, men with half their heads blown off and their brains falling over their faces – some with their abdomens torn open and their entrails hanging out – others stretched out with livid faces and blood-stained mouths, and unblinking eyes staring straight to heaven. Oh wives and mothers and sweethearts, what will this victory mean to you? Yet nature very readily adapts itself to its environment and can look on all these horrors without a shudder. But I should feel sick and almost terrified if I saw a man break his leg in the streets of London.

Unfortunately, as in previous victories (like the Canadian advance on Vimy Ridge during the Second Battle of Arras) the generals weren’t prepared to exploit the gains won by the valor of ordinary fighting men. Indeed, the logistical difficulties involved in bringing up fresh troops and ammunition shouldn’t be underestimated. Martin’s account gives some idea of the frenetic activity required to sustain the initial advance, as he wrote on June 10:

The RE Field Companies are working hard on pit-prop roads and trench tramways. They have carried them as far as the old front line and are now working across no-man’s-land. Their hardest work is now commencing. It is an extraordinary scene of animation. Wagons and lorries full of materials are arriving in constant succession and hundreds of men are unloading and carrying and putting in place…

Although Plumer urged Haig to press their advantage by continuing the attack, the BEF commander insisted on waiting until late July, giving the Germans almost eight weeks to adjust and enhance their defensive positions on the Gheluvelt Plateau and high ground to the east of Ypres, including around Passchendaele – a small Flemish village fated to become synonymous with mindless slaughter.

See the previous installment or all entries.